Cracking the Mirror: Autobiography and Self-Portraiture

James A. W. Heffernan

The Routledge Companion to Literature and Art, ed. Neil Murphy, W. Michelle Wang, and Cheryl Julia Lee (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2023).

Anyone who studies either autobiography or self-portraiture knows that each of these two forms of self-representation has attracted a formidable number of critical studies. As I write these words in June of 2022, for instance, a quick check of the MLA online bibliography tells me that there are no less than 23,608 studies of autobiography. Staggering as it seems, this number pales by comparison with studies of self-portraiture, which--according to the online catalogue of the Getty Research Institute--top out at 76,567. But guess how many studies there are of autobiography and self-portraiture? So far as I can tell, the answer is precisely one--a dissertation written in 2005.1 What follows, then, should instantly double the scholarship on this strangely neglected topic.2

Let us examine it by means of mirrors. Most of us use them to look at our own reflected faces at least once a day, and for obvious reasons they furnish what is surely the best-known metaphor for imitation--or representation-- in literature and art. In the words that Shakespeare's Hamlet speaks to the players, we might say that all arts of representation--not just the theater--aim "to hold as 'twere the mirror up to nature" (Hamlet 3.2.20-21). When we turn our focus on visual art, this metaphor for imitation turns almost literal. According to Leon Battista Alberti, the most influential art theorist of the Italian Renaissance, art originated from the study of reflections. In Della Pictura (1435), his treatise on art, Alberti says that painting was invented by Narcissus, who fell in love with his own reflection in a shaded pool. "What else," writes Alberti, "can you call painting but a similar embracing with art of what is presented on the surface of the water in the fountain?" (Alberti, 64).

Alberti's rhetorical question prompts many more questions of a different kind. Quite apart from what we now know of pre-historic cave paintings, which depict animals rather than people (let alone narcissistic young men), Narcissus hardly seems to radiate the godlike power that Alberti imputes to ancient artists such as Zeuxis and all "master painter[s]" of any age (Alberti 64). Unlike them, Narcissus is not a maker of art but the dupe of his own reflection, which so entrances him that he dies of unrequited longing for it.

In the third century of our era, long before Alberti wrote his treatise, a Greek rhetorician named Philostratus defined Narcissus as a figure both powerless and paralyzed. Commenting on a painting that he saw while lodging in a seaside Neapolitan villa and that might have looked something like this Pompeian fresco (SLIDE 1),

SLIDE 1. Narcissus. Pompeian fresco probably of the first century C.E.

Philostratus writes, "The pool paints Narcissus, and the painting represents both the pool and the whole story of Narcissus." In other words, this might be called a metapicture, a painting about painting. But unlike Alberti, Philostratus does not consider Narcissus himself a painter. On the contrary, he sharply distinguishes Narcissus from the painter and--just as importantly--from the viewer of the painting that represents him. Directly addressing the painted young man, Philostratus says,

Narcissus, it is no painting that has deceived you, nor are you engrossed in a thing of pigments or wax; but you do not realize that the water represents you exactly as you are when you gaze upon it, nor do you see through the artifice of the pool, though to do so you have only to nod your head or change your expression or slightly move your hand, instead of standing in the same attitude; but acting as though you had met a companion, you wait for some move on his part. Do you then expect the pool to enter into conversation with you? Nay, this youth does not hear anything we say, but he is immersed, eyes and ears alike, in the water and we must interpret the painting for ourselves. (Philostratus, 91)

In this light, Narcissus makes a very strange model for the artist. Neither a maker of art nor an articulate viewer of it, he is simply and fatally immobilized by it. He has nothing to show or tell us about the process of representing anything, including himself, and nothing to say about the meaning of the painting or of the reflection it depicts--the painting within the painting. He leaves us to interpret the painting for ourselves.

Without further probing Philostratus' comments on a particular painting, let us grant that Alberti may simply be using the legend of Narcissus to define painting as an art of replication, of reproducing visible objects as accurately as possible. Just after calling Narcissus the inventor of painting, in fact, Alberti cites Quintilian--a professor of rhetoric in ancient Rome--as saying "that the ancient painters used to circumscribe shadows cast by the sun, and from this our art has grown" (Alberti, 64). Pliny the Elder thought likewise. In his Natural History of the first century of our era, Pliny claimed "there is universal agreement [sic] that [painting] began by the outlining of a man's shadow" (35.15): an event recalled in paintings such as this one (SLIDE 2):

Slide 2. David Allan, The Origin of Painting (1775).

National Galleries Scotland

But the legend of primal circumscription--whether or not it could ever be proven--hardly explains the origin of self-portraiture. For even with mirrors, it would be difficult if not impossible to trace the shadow of one's own profile without moving that profile and thus breaking the trace. On the other hand, a painter can depict what he sees in the mirror, and many have done so. Before the invention of photography in the 1840s, the only way an artist could produce a recognizable likeness of himself was to paint his own reflection--"embracing (it) with art," as Alberti said. The act of doing so constitutes what I would call the ground level of self-representation, which is self-replication or self-duplication.

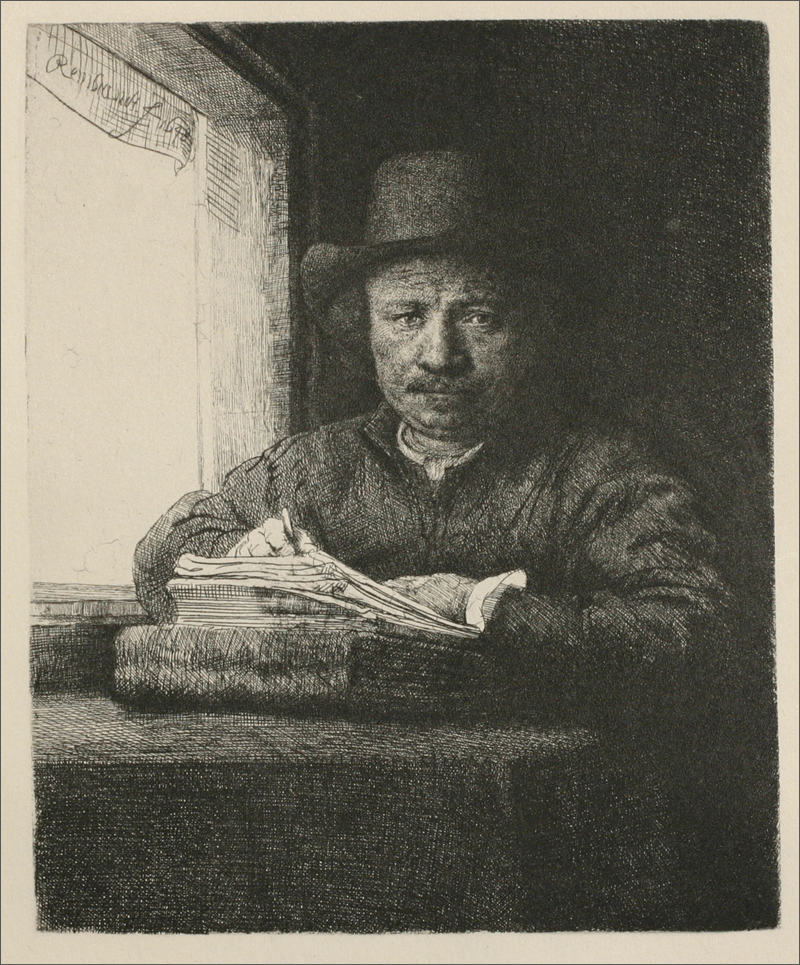

Take for instance this picture of himself that Rembrandt etched in 1648 (Slide 3):

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait Etching at a Window (1648).

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Sylmaris Collection, Gift of George Coe Graves, 1920.

Here the 42-year-old artist delineates what he presumably sees in the mirror before him. Unadorned by any of the finery we so often see in his other self-portraits, uncolored by any of their flamboyance or dramatic flair, he sits at his table by a window practicing his craft as an etcher of pictures such as this. Here, according to H. Perry Chapman, a specialist in Rembrandt's self-portraits, Rembrandt "radically redefine[s] his self." Abandoning "the role of gentleman-virtuoso," he portrays himself "as an artist in the studio, autonomous in his professional identity. . . No longer play-acting, he sits at a table drawing probably with an etcher's needle on a plate. No longer elegantly costumed, he wears his mundane studio smock and a prosaic, middle-class hat, which brings to mind the 'freedom hat' widely used as a symbol of Dutch liberty in political allegories of the independence of the Netherlands. . . . . In 1648 the Treaty of Munster finally ended the war with Spain, bringing official recognition to Dutch independence. . . ." (Chapman 19-21).

Chapman's point is well taken. Rembrandt's simple hat and smock reinforce the authenticity of the picture as a window on a particular time of Rembrandt's life at a crucial year in Dutch history, and as a window on a particular moment of Rembrandt's working day: even the hour can be approximately gauged from the angle of the light slanting through the window. "This is just what the mirror reflected," writes Halla Beloff, a psychologist. "He is not dressed for an exotic never-land. The window places him mundanely in his house. The work is openly revealed, and so, we feel, is the artist. . . . What we see is a serious craftsman, indeed hard at work, a frown of concentration between his eyes. He examines himself. He is not interested in manipulating our view of him; he is not interested in us. . . . This is how he was" (Beloff 31).

Relatively speaking, Chapman and Beloff are right. In the 1648 etching, Rembrandt represents his working life far more realistically than he does in a painting made about ten years earlier, where he poses as the Prodigal Son with his new wife Saskia (SLIDE 4):

SLIDE 4. Rembrandt van Rijn, Rembrandt and Saskia in the Parable of the Prodigal Son (c. 1637).

Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister.

For all its play-acting, however, I suspect that as compared to the workaday etching, this painting more faithfully captures the spirit of Rembrandt's shirking life, the mood of gaiety and abandon with which he might well have celebrated his new marriage--especially at a time when his growing success gave him the means to do so. But leaving aside such speculation, look again at the etching. Is this exactly what the mirror reflected, as Beloff claims? The answer is no, not unless its reflections came only in black and white. In this respect, at least, the flagrantly theatrical painting is more realistic. If we resist that idea, it is only or chiefly because we associate the tonal sobriety of the print with understatement, with restraint, and therefore with honesty--the uncolored truth. But how much truth does a black-and-white etching tell about a colored reflection? How well does Rembrandt's rich chiaroscuro and delicate cross-hatching duplicate it? This is just one of the many questions raised by the claim that any picture perfectly duplicates what the artist saw when he created it--in the mirror or anywhere else.

When Beloff claims that Rembrandt's etching is "just what the mirror reflected," we have absolutely no way of verifying this claim, no independent access to that mirror and not even any guarantee that he was looking at one. As we look at the etching, the eyes of Rembrandt look searchingly at something we cannot see, something outside the picture but so clearly occupying the place of the viewer that he seems to be looking at us. We find ourselves in this position whenever we look at a picture of the artist at work and facing us--as in Velazquez Las Meninas, painted in 1656, just a few years later than Rembrandt's etching (SLIDE 5):

SLIDE 5. Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas (1656).

Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado.

In this painting of a painter at work beside his subjects, the back of the canvas blocks our view of whatever he is putting on it. The framed couple in the deep background hint at what he might be looking at--but only if we construe the couple as reflections in a mirror: reflections of a couple--the royal couple, in fact--occupying the place where we stand to view the painting. In that case, of course, what the painter sees before him and is shown to be depicting has almost nothing to do with the painting we see here. Even if we read the framed couple as a figures in a painting within the painting, and even if we imagine that the painter works before a mirror large enough to reflect everything that we now see in the painting, including himself, we cannot help occupying the space targeted by his gaze, and thus feeling that we occlude at least part of what the mirror reflects. In any case, the painting does not represent the painter in action--applying a brush to his canvas--but rather holding it steady, posing before a canvas we cannot see. To see his reflection in a mirror, the painter must look away from his canvas, just as the etcher must look away from his plate. He cannot simultaneously do his work and duplicate the mirror's reflection of his doing it.

If we now return to the 1648 etching (SLIDE 3), we see Rembrandt looking up from his plate. Do the compressed lips, the lowered double chin, the steady eyes, and the creased forehead express the mood of concentration with which he is working, or do they join to form just one more expression assumed for the mirror, taking its place with others such as this one of 1630 (SLIDE 6):

SLIDE 6. Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait with Beret (1630).

Here the pursed lips, the canted eyebrows, and the wide staring eyes seem theatrical or comic and hence unrealistic. But they seem unrealistic only if we believe--as G.E. Lessing once decreed--that visual art should represent nothing transitory, no fleeting expression (Lessing 20). They seem unrealistic only if we believe that the "real" Rembrandt--beneath and behind all that trumpery and posturing and mugging we see elsewhere--was the man limned in the 1648 etching: a man who habitually kept his mouth neatly shut, his brow tensed, and his gaze unwaveringly firm. Even if that were true, can we ignore the signs of artifice in this work? The window, for instance, not only gives the picture its artfully composed light but also reminds us of Alberti's master trope for painting: visible forms enclosed by a window frame (Alberti 64). Besides that, the strip of blind just below the top of the window shows us something Rembrandt could certainly not have seen in his mirror, for here he has signed his name and inscribed the date of the etching.

Do I labor the obvious here? It may seem so. It may seem needless to argue that no artist can ever duplicate what he or she sees in the mirror, and that in any case we have no independent access to what he or she might have seen there. But if these points are obvious and incontestable, I do not know what H. Perry Chapman means when she says that an artist posing before a mirror has abandoned play-acting, or what Halla Beloff means when she says that Rembrandt shows us "just what the mirror reflected." To study this etching is to see the impossibility of ever closing the gap between self and self-representation in visual art, between the artist who wields the brush or etching needle and the artist who poses, between a living body--even when reflected in the mirror--and a depicted or delineated one. I stress this point because a comparable gap separates the writing self from the written self in the literature of autobiography, whether fictionalized or not. Consider the opening stanza of the third canto of Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, Lord Byron's autobiographical travelogue in verse. Having written two cantos about his travels around the Mediterranean in 1810-11, when he was in his early twenties, he now records his embarkation from England in late April of 1816, two months after being decisively separated from his wife. He begins by apostrophizing their infant daughter Ada, who has been taken by his estranged wife and whom he will never see again:

Is thy face like thy mother's, my fair child!

Ada! sole daughter of my house and heart?

When last I saw thy young blue eyes they smiled,

And then we parted, --not as now we part,

But with a hope.--

Awaking with a start,

The waters heave around me; and on high

The winds heave up their voices: I depart,

Whither I know not; but the hour's gone by,

When Albion's lessening shores could grieve-or glad mine eye.

CHP 3:1

We have here almost a picture made with words, a typographical image of separation. The stanza breaks precisely in the middle, graphically signifying two kinds of rupture: the wrenching separation of the speaker from his daughter, which assumes a painful finality when compared with a previous parting, and the sudden experience of waking up, which decisively breaks the mood of reverie established in the first half of the stanza.3 Yet even as it registers and represents rupture, the stanza demands to be seen and read as a whole. It begins and ends in a present tense that consumes nostalgia, that denies the emotional impact of the fissure between past and present, that defiantly asserts the speaker's indifference to the very act of parting: the sight of "Albion's lessening shores"--the dwindling coast of England--can no longer move him in any way.

The speaker's determination to deny the very split which this stanza so graphically reveals is reinforced by the mode of narration here. As Jerome McGann has said about the whole poem, the stanza makes "no distinction between the narrator's virtual present and a past series of events about which he writes" (McGann 33). In the first four and a half lines, the speaker's reverie occurs at the very same time as his narration of it (McGann 34). But if we read Byron's stanza innocently, as if for the first time, we cannot know that its first four and a half lines express a mood of reverie until we learn that the speaker has been jolted awake. Only then are we asked to believe that the lines we have just read have not been uttered by an already awakened speaker, but rather have been spoken or somehow written within a dream. The second half of the stanza then implies something only a little less likely: that a dreamer could not only start speaking at the instant of awakening but also instantly transcribe his speech in verse, scribbling out a Spenserian stanza on the deck of a pitching ship. Byron thus exposes the illusion as such in the very act of generating it. Even as he tries to close the gap between the experiencing self and the writing self, between the dreaming voyager suddenly jolted awake and the poet deliberately shaping a stanza, he is forced to disclose it.

What is implied in this first stanza becomes explicit in the third, where the poet shifts to the past tense. Here he presents himself as the author of a poem about a gloomy, introverted, alienated wanderer named Childe Harold, the titular hero of the two cantos that Byron published in 1812, when he was 24:

In my youth's summer I did sing of One,

The wandering outlaw of his own dark mind;

Again I seize the theme then but begun,

And bear it with me, as the rushing wind

Bears the cloud onwards: in that Tale I find

The furrows of long thought, and dried-up tears,

Which, ebbing, leave a sterile track behind,

O'er which all heavily the journeying years

Plod the last sands of life,--where not a flower appears.

CHP 3.3

The I of this third stanza--the pronoun I-- clearly differs from the I of the first two. In the first two stanzas, the voyaging narrator uses the present tense to tell the story of an actual embarkation, and of his reckless surrender to the elements: "I am as a weed," he says, "Flung from the rock, on Ocean's foam, to sail. " By contrast, the I of stanza 3 uses the past tense to say what he has written. So here the literal language used to record his physical embarkation becomes figurative; it figuratively signifies the renewal of composition. The man driven by wind and waves--the passive object of elemental forces--becomes himself a wind-like force driving his cloudlike theme along. Finally, the poet represents himself as also a reader--a reader looking back on a text that becomes a sterile tract of sand, a parody of the voyager's wake, even as he sets out to write again.

Before Harold reappears in the poem, therefore, Byron represents himself as an I with two selves: the speaking self of the narrating traveler, who is literally in motion and who immediately translates his experience into words, and the writing self of the dramatized poet, the poet who can read what he has written and comment on his own act of writing. Both selves persevere to the end of the poem. But the dramatized poet never supersedes the narrating traveler. Instead, he periodically dissolves into the traveler, as in this stanza from the latter part of canto 3:

But let me quit man's works, again to read

His Maker's, spread around me, and suspend

This page, which from my reveries I feed

Until it seems prolonging without end.

The clouds above me to the white Alps tend,

And I must pierce them, and survey whate'er

May be permitted, as my steps I bend

To their most great and growing region, where

The earth to her embrace compels the powers of air.

CHP 3.109

The I of this stanza first signifies the dramatized poet who has been reading "man's works" (the books of Rousseau, Voltaire, and Gibbon) as well as writing his own poem, endlessly feeding "this page." But in suspending this page, in lifting his pen from the paper he has been writing on, the dramatized poet once more becomes the narrating traveler. Writing as if he were speaking, reading the book of` nature instead of man-made texts, bending his steps to the Alps, he is literally on the move again. First and last, then, Byron represents himself as a quester: a traveling narrator projected by the dramatized poet who also projects--but ultimately rejects--Childe Harold. What remains is the quintessentially Byronic pilgrim, a man with neither a determinate self nor a determinate destination, a personality in the act of perpetually becoming.

Byron's poem thus exemplifies two features common to self-representation in art as well as in literature: first, the impossibility of replicating one's life at any moment, reflecting it perfectly, exactly reproducing a mirror image of it; second, the inevitability of self-projection, self-dramatization, playing a role. Besides Harold, the title character, we have the dramatized poet and the traveling narrator, the highly self-conscious creator and the wandering self--the wandering I and eye--that he creates. Since the word personality springs from the Latin word for mask (persona), we might treat both of these personalities as masks for Byron's "real" self. But to think we can find his real self by stripping away the masks of the poem is like imagining that we can find the real Rembrandt by stripping off all of his costumes, rejecting all of his poses, dismissing all of the ways in which he depicts himself. Difficult as it may be to grapple with the trio of selves that Byron generates in CHP, doing so may help us to grapple with the daunting number of self-portraits painted and drawn by Rembrandt--more than ninety in all.

"Why so many?" is the question repeatedly asked. According to some art historians, Rembrandt's self-portraits served to advertise his virtuosity, his social status, and the dignity of painting itself (Wetering 12, Chapman 13). But there's a problem with this formulation: only a small number of his self-portraits cast him in a truly dignified light. Besides posing as a plumed young dandy in 1629 (SLIDE 7) and a luxuriantly sleeved grandee in 1639 (SLIDE 8), he also cast himself as an ugly beggar (SLIDE 9) and a screaming lout (SLIDE 10):

SLIDE 7. Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait Age 23.

Boston, Isabella Stuart Gardner Museum.

SLIDE 8. Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Potrrait Leaning on a Stone Sill. Etching (1639).

Prague, National Gallery.

SLIDE 9. Rembrandt van Rijn, Beggar Seated on a Bank (1630). Etching.

Princeton University Art Museum.

SLIDE 10. Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait Open Mouthed, as if Shouting (1630). Etching on laid paper.

Washington, DC: National Gallery.

Once again, why so many self-portraits? Let me answer in two stages. The dazzling variety of ways in which Rembrandt represents himself springs in part from something as universal as self-presentation in everyday life, the title of a well-known book by Erving Goffman. Citing and summarizing Goffman's argument, Beloff writes that in everyday life we are all more or less acting, that "we perform our parts to communicate as best we can the vision of our personal autobiography and our social status" (Beloff 25). In other words, in the selves we present to others--in the faces we prepare to meet the faces we shall meet, as Eliot's Prufrock says--we strive to fuse what we think of ourselves with what we want other people to think of us. But the fusion is seldom perfect, and social pressure leads instead to a multiplicity of roles. In his autobiographical Confessions (written in the late 1760s), Jean-Jacques Rousseau recalls that his childhood reading of Greek and Roman heroes fired his imagination so much that he "believed himself to be Greek or Roman; I became the character whose life I read." (Rousseau 8). Later on, recalling one of the many long walking trips he took as a young man, he writes of finding his true self in solitude on the road: "Never have I thought so much, existed so much, lived so much, been myself so much, if I dare speak this way, as in these travels I have made alone and on foot" (Rousseau 136, emphasis mine). But if we conclude that Rousseau's true self lies in solitary walking, how do we explain what he suddenly felt in his youth while posing as an English Jacobite among a group of French Catholics that he met in his travels? During the course of an evening walk with one of them, a charming older woman, his tongue-tied embarrassment and gnawing fear of exposure were suddenly vanquished when she put her arm around his neck and kissed him. "The crisis," he writes, "could not have happened more opportunely. I became lovable. It was time for it. She had given me that confidence the lack of which has almost always kept me from being myself. I was so at the time. Never have my eyes, my senses, my heart and my mouth spoken so well. . . ." (Rousseau 211, emphasis mine). I was myself, says Rousseau, at the very moment when I was posing as someone else. Here the inner self--the would-be soul of the individual--merges with the social self. To see that Rousseau suddenly discovers himself--or a self--even while masquerading as an Englishman and playing the role of a glib lover is to see how much other people can shape our conception of ourselves.

Writers and artists know this only too well. Once they acquire a reputation, they must accommodate a public self along with the private one. In a little essay by Jorge Luis Borges called simply "Borges and I," the famous Argentinian writes:

It is to the other man, to Borges, that things happen. . . . of Borges I get news through the mail and glimpse his name among a committee of professors or in a dictionary of biography. I have a taste for hourglasses, maps, eighteenth-century typography, the roots of words, the smell of coffee, and Stevenson's prose; the other man shares these likes, but in a showy way that turns them into stagy mannerisms.

Inevitably, it seems, Borges deploys the language of theater to represent his public self, but then he candidly concludes, "Which of us is writing this page I don't know" (Borges 279).

Turning back from Borges to Rembrandt, then, we might first explain the astonishing variety of his self-portraits by observing that artists and writers alike continually engage in a heightened version of everyday self-presentation, of the acting we do with each other to shape our personalities for social ends. But when Rembrandt etches himself as an ugly beggar or a screaming lout, what social advantage does he gain? Looking elsewhere for his motives, we must surely recognize that Rembrandt drew and painted his pictures almost as if staging a play: that he chose his sets, costumes, and lighting for theatrical effect, and that he used himself--his own face and body--to explore the expressive possibilities of art, its capacity to represent what Alberti called "the movement of [the] soul" in each of its figures (On Painting 77). In drawing himself as a screaming lout, is he representing a personal moment of anguish or preparing himself to paint the agonized face of Christ on the cross, as he did in 1631? (SLIDES 11, 11A)

SLIDE 11. Rembrandt van Rijn, Christ on the Cross (1631).

Le Mas-d'Agenais, Lot-et-Garonne, église Saint-Vincent.

SLIDE 11A. Rembrandt, Christ on the Cross, detail.

Whether posing as himself or as someone else, such as the Prodigal Son, Rembrandt could not pose at all without playing a role, but always a role that expressed some fraction of his identity as an artist and thereby shaped the self he was presenting. Rousseau begins his Confessions with the potent words, "je forme." "I am forming, I am shaping," he writes, the inimitable and unprecedented story of myself. It will include the shameful as well as the noble, he promises, and he does indeed confess to such things as exposing himself to young women in dark alleys, abandoning a friend in need, and falsely accusing a servant girl of a theft that he himself committed. Nevertheless, Rousseau forms and shapes his narrative to contrapose the best and worst features of his character, and to highlight the crucial stages of his life, as when Book I ends with his fateful departure from Geneva at the age of sixteen.

Does this mean that Rembrandt likewise shapes the story of his life in his self-portraits? I venture to say no. The familiar claim that Rembrandt's self-portraits add up to an autobiography simply will not survive close scrutiny, especially when we compare them to the more or less coherent and comprehensive narratives wrought by literary autobiographers such as Rousseau. The portraits do indeed show Rembrandt growing older: from the round, smooth face of youthful intensity and shadowed, penetrating eyes (SLIDE 12)

SLIDE 12. Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait as a Young Man (1628-29).

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum.

through the joyous years with Saskia (as in the Prodigal Son painting) and the sobriety of middle age (as in the 1648 etching) to the majesty of old age, with hair turned white and face creased by wisdom born of suffering and pain (SLIDE 13).

SLIDE 13. Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait with Two Circles (c. 1665-1669). Oil on canvas.

London, Kenwood House.

But do any of Rembrandt's self-portraits reveal the genesis of his pain? Does any one of them show him mourning the death of his wife Saskia in 1642, or mourning the three of their four children who died in infancy, or leaving his house in 1660 after bankruptcy forced him out of it? At best, the portraits illustrate a story that must be constructed from the verbal record of Rembrandt's life. To make the portraits alone yield an autobiographical narrative is to imagine--for instance-- that from 1629 to 1631 Rembrandt somehow lurched from the elegance of a Renaissance courtier to the desperation of beggary and back again to prosperity--all in less than two years' time.

Time itself makes the crucial difference between self-portraiture and autobiography. When Rembrandt looked in the mirror at any time of his life, all he could see was his then-present self. He could dress as he pleased; he could pose as a saint or a beggar or a courtier or a plain old etcher working at his desk. But he could not--or would not--change the age of the face that looked back at him. If we seek a literary analogue for Rembrandt's self-portraits, therefore, they suggest not so much the chapters of an autobiography as the pages of a diary--so long as we recognize that they seldom record the daily facts of Rembrandt's life and that each is shaped as a work of art. What does Rembrandt reveal in his self-portrait with Saksia in 1635, one year into their marriage? That he was a happy husband with an imposing house, revelling in all the costly furnishings and costumes and food and drink that his newly acquired wealth could buy? That he was a wild drinker? Or--hiding in plain sight-- that he was a brilliantly theatrical painter capable of staging this scene (note the drawn curtains at right), catching the tone and texture of its many fabrics, placing the raised glass as if it were an elevated host, and geometrically linking the contrasted figures--one sitting, one standing, one abandoned, one prim--with the half-circle of the man's draped arm? In pictures such as these, Rembrandt not only marks the stages of his life but also shows us the development of his style, which is of course an integral part of his life as an artist.

For this very reason, we have only to imagine this scene re-constructed by the sixty year old Rembrandt to see the difference between autobiography and self-portraiture.

Autobiographers bring to the task of re-creating their past all they have learned or experienced in the meantime--in life or in the art of writing. If the sixty-year old Rembrandt were to re-create the period represented by his self-portrait as the prodigal son, it would look drastically different. Consider for a moment something roughly comparable: the steamy life of a teenager named Augustine in the fleshpots of ancient Carthage. How does that life look in retrospect to the spiritually regenerated man he became? We find out in Book 3 of Saint Augustine's Confessions, written at the end of the fourth century of our era, long before the Confessions of Rousseau. Recalling his hyper-sexed adolescence, Augustine writes: "I came to Carthage, where a cauldron of illicit loves leapt and boiled about me. I was not yet in love, but I was in love with love, and from the very depth of my need hated myself for not more keenly feeling the need. . . . Within I was hungry, all for the want of that spiritual food which is Thyself, my God" (Confessions 3.1). Here adolescent lust is viewed through the lens of maturity. The teenage, pagan, half-educated, irrepressibly hormonal Augustine could not possibly have portrayed himself in these terms. Only the mature, spiritually disciplined, rhetorically sophisticated Christian that he became could manage the sort of brushwork required to set his youthful self within a framework of ultimate redemption.

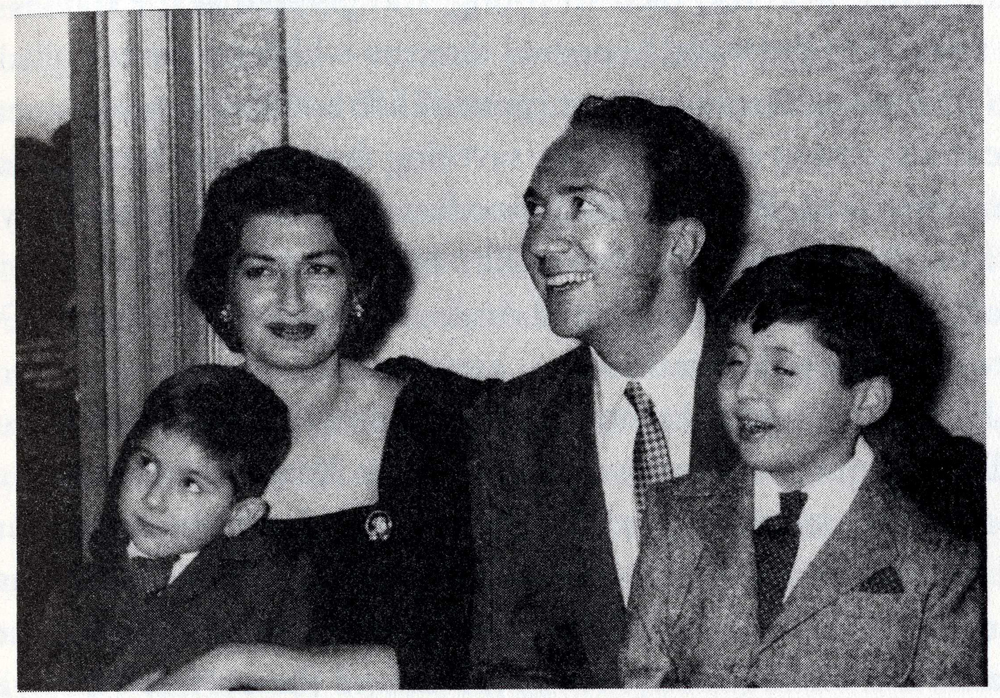

Autobiography stages an ongoing negotiation between past and present, between the remembered self and the remembering self, between the life once lived and the task of reconstructing that life in words. Memory never seals the gap between them. In his own Confessions, Rousseau claims to have "unveiled [his] interior as [God himself] has seen" it. But he admits that he may have now and then added "some inconsequential ornament . . . to fill up a gap occasioned by my lack of memory" (5). And of course that is only a tiny fraction of what autobiography adds to the past. In a recent book called Istanbul, his autobiographical portrait of an ancient city, the Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk juxtaposes photographs of his boyhood self with his mature reflections on it. Which is the more exact reflection--the photograph of the boy or the words of the man? From the photograph of himself and his brother with his parents at a wedding (SLIDE 14), for instance,

SLIDE 14. Orhon Pamuk as a child (far left) with his parents and older brother.

we might guess that the little boy at lower left grew up--almost literally--in the lap of a happy family. Only his unsmiling mouth and the restless tilt of his body and his sidelong glance at something outside the frame hint of what the boy came to know and the man reconstructs. "If ever evil encroached," he writes,

if boredom loomed, my father's response was to turn his back on it and remain silent. My mother, who set the rules, was the one to raise her eyebrows and instruct us in life's darker side. If she was less fun to be with, I was still very dependent on her love and attention, for she gave us far more time than did our father, who seized every opportunity to escape from the apartment. My harshest lesson in life was to learn I was in competition with my brother for my mother's affections. (Pamuk 16)

How much of this accurately represents what the boy felt--but obviously could not articulate--at the moment the photograph was taken? We have no way of knowing because no autobiographer can directly access his or her earlier self, can see it without the intervention and interference of his present thoughts, feelings, and language.

Well before Pamuk's time, this kind of interference turns up in the poetry of Wordsworth, Byron's older contemporary. At one point in The Prelude, the autobiographical epic that Wordsworth spent much of his life writing and re-writing, he re-enacts the legend of Narcissus--with a radical difference. He defines autobiography as the impossible task of looking through the mirror, through the reflection of one's present self. In trying to recover his past, he says, he is like someone hanging over the side of a boat and looking down through still water to see what lies beneath the surface:

Yet often is perplexed and cannot part

The shadow from the substance, rocks and sky,

Mountains and clouds, reflected in the depth

Of the clear flood, from things which there abide

In their true dwelling; now is crossed by gleam

Of his own image, by a sun-beam now,

And wavering motions sent he knows not whence,

Impediments that make his task more sweet;

Such pleasant office have we long pursued

Incumbent o'er the surface of past time

With like success.

(Prelude 1850 4. 263-70, emphasis added)

Unlike painters, autobiographers seldom if ever describe their "own image," their own reflection: what they see in a mirror or mirror-like surface of still water. Here the poet's own image, which symbolizes everything he is now, in time present, is one of the reflections that distract him from the underwater "substance" of his past. Yet the reflections are also an impediment that sweetens his task and surely heightens his diction. He can no more ignore the reflections on the surface of the water, including his own face, than he can reconstruct his past without presently reflecting on it, without using a language generated by his intervening experience. Later on in the poem, he recalls the impression made upon his schoolboy self by the sight of a shepherd standing on a distant hill. To the eyes of his schoolboy self, he says, the shepherd was

A solitary object and sublime,

Above all height! like an aerial cross

Stationed alone upon a spiry rock

Of the Chartreuse, for worship.

(Prelude 1850 8. 272-75, emphasis added)

To recall what he saw as a boy, he uses the language of a full-grown man. The cross of the Alpine monastery of the Chartreuse does not come from the depths of Wordsworth's boyhood; it's a reflection of his present self. Even if the English schoolboy had possessed the word "sublime" in his vocabulary, he could not have known the cross of the Chartreuse, which Wordsworth did not see until he first traveled to the Swiss Alps as a young man of 20. This later experience, which has now become part of his present self, crosses the memory of his past self like the gleam of a reflected sun-beam or the image of his own face in still water. His present self overlies the picture of his past self.

Can visual art do anything like this? Can a self-portraitist re-create only what he finds in the mirror as he paints, or can he somehow look back through the lens of time at his younger self? Consider the possibilities. An artist can surely produce a sequence of self-portraits at one time, as David Hockney did in the early sixties, when he produced a set of sixteen etchings based on his first trip to America and called it--with a nod to William Hogarth--A Rake's Progress. As a visual narrative, these etchings tell the story of his would-be idle, drunken wanderings in New York and Washington and also reveal his coming out as a gay artist fully engaged with contemporary culture, as in this etching (SLIDE 15), where Hockney himself is the newly-dyed Lady Clairol blonde for whom the door to adventure is opening.

SLIDE 15. David Hockney, The Start of the Spending Spree and the Door Opening for a Blonde.

A Rake's Progress (1961-63), Plate 3. Etching. Acquatint. © David Hockney.

Yet like the self-portraits of Rembrandt, Hockney's etchings of himself look less like chapters of an autobiography than diary entries--and in this case diary entries dating from just one period of the artist's life. So the question remains: can self-portraiture do anything like what autobiography does? Can it represent the stages of an artist's life, or depict an earlier stage of that life from the viewpoint of a later one?

SLIDE 16. David Bailly, Self-Portrait with Vanitas Symbols (c. 1651). Oil on wood.

Leiden, Stedelijk Museum De Lakenhal

Consider a painting by one of Rembrandt's contemporaries: David Bailly (1584--1657), a Dutch painter based in Leiden (SLIDE 16, and my thanks to Jan Blanc for alerting me to this picture many years ago). In this self-portrait of about 1651, painted when he was 67, Bailly includes several symbols of Vanitas, of the vanity and transiency of life: dropped and drooping blossoms, a skull, a tall glass of wine, and a just-snuffed candle with a wispy thread of smoke rising from it, so that we can almost hear the words of Shakespeare's Macbeth on learning that his wife is dead: "Out, out, brief candle! / Life's but a walking shadow. . . ." (Macbeth 5.5.23-24). Just behind the candle, in fact, is an oval picture of Bailly’s lovely young wife, who died shortly before this picture was painted. But the most remarkable thing about this painting is that it represents the painter at two different stages of his life: past and present, young and old. Still more remarkably, the painter's older self--his present self--is enclosed within an oval picture just to the left of the candlestick, while his boldly confident younger self, his past self, appears unenclosed at left. Far bigger and more imposing than any other figure depicted here, this young painter holds up for us the oval portrait of what we can recognize as his older self.

In thus juxtaposing two versions of himself, Bailly totally subverts the conventions of self-portraiture. Normally, a self-portrait represents what the painter sees in the mirror at the time he or she paints. Since the young man is the only figure within the painting who is unenclosed by an oval or rectangle, we are visually prompted to read him as a depiction of the painter's present self, and all of the enclosed figures as pictures dating from some indeterminate past. But as soon as we recognize the oval picture of the old man as an updated version of the young painter at left, we must realize that the presence of this young painter in the painting is pure fiction--as fictional as the would-be categorical difference between enclosed and unenclosed figures in a painting. As soon as the artist paints himself at any age, he is framed within the picture and thus defined as already past, like the snuffed-out candle standing right beside the artist's framed self-portrait as an old man. So far as I know, this is as close as any self-portrait has ever come to the retrospective core of autobiography.

Yet even as it does so, it reveals again the fictiveness of self-portraiture. It reminds us that self-portraiture resembles autobiography in nothing so much as its incapacity to replicate the artist perfectly. Neither writers nor artists can exactly mirror or duplicate themselves, can catch themselves in the act of producing the work we have before us. Writers reconstruct a past self that is always seen through the lens of time; artists choose a role--a pose and expression--that can best enact or dramatize some fraction of their character, some fragment of what they feel or imagine for themselves or for the sake of their art. To portray themselves convincingly, then, artists must find new signs of self-expression, working with rules that can never be fully codified.

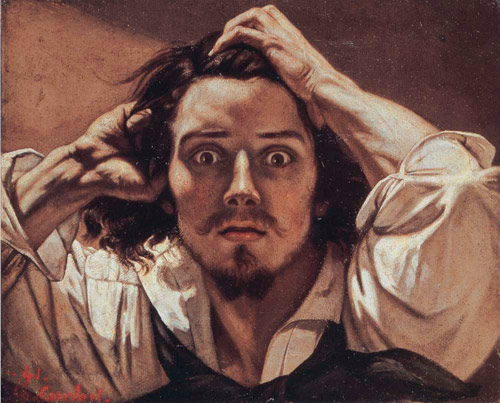

Consider a self-portrait by Gustave Courbet, painted around 1844, when he was 25 (SLIDE 17):

SLIDE 17. Gustave Courbet, Le Désespéré [The Desperate Man] (1843-45).

Paris, Conseil Investissement Art BNP Paribas.

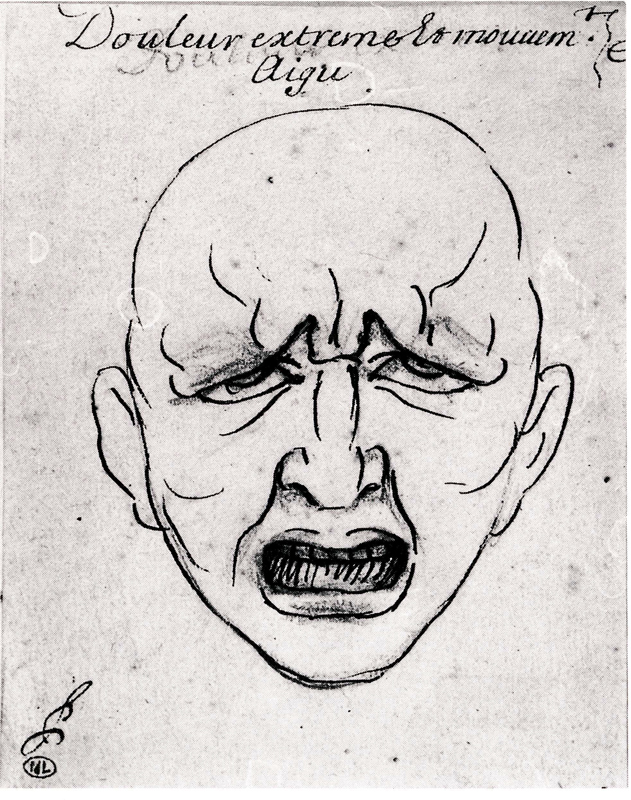

Biographically, we know this was painted after Courbet's work had been several times rejected by the jury for the annual Salon exhibition in Paris. We also know that he was growing disenchanted with his Romantic ideals, and that in later years he recalled, "How I was made to suffer in my youth!" None of these facts, however, would tell him how to portray his state of mind and feeling in this period, so art historians sometimes link this painting to rules of expression formulated in the seventeenth century by the renowned French painter and art theorist Charles Le Brun. Le Brun argued that the key to expressing strong emotions lay not in the eyes but in the eyebrows, followed by the mouth, "which most particularly indicates the movements of the heart" (qtd. Montague 128, 132). Here in SLIDE 18, for instance is Le Brun's face of anguish--"doleur extrȇme"--with its eyebrows crushed down over the eyes and its mouth wide open.

SLIDE 18. Charles Le Brun, "doleur extrȇme,"

Conference sur l'Expression Generale et Particuliere des Passions

(Verona, 1751).

To compare this face with Courbet's Desperate Man is to see how much Courbet re-makes the rules of Le Brun. With his mouth closed and his eyebrows barely raised, Courbet's figure signifies its anguish chiefly by means of two features that Le Brun either underestimates or does not notice at all: the wide staring eyes and the hands entangled in his hair--something wholly missing from the bald dome of Brun’s anguished face. Tearing one's hair out is, of course, a sign of desperation. But Courbet's figure does not tear his hair; he clutches at it. Furthermore, the hands and bent arms together compose a diamond framing the circle of the face--a circle repeated in the scoop neck of the dark vest beneath it. Artfully drawing almost the whole of his upper body into this geometically defined space, Courbet deploys signs of desperation that Le Brun largely or wholly ignores--especially the hands. Though differently angled--the one a peaked roof at the top of the head, the other facing out--each of them helps to shape the diamond containing the face.

This painting could be dismissed as just one more exercise in self-dramatization. "Courbet's self-portraits," we have lately been told, "rehearsed late-Romantic personae: dandy, dreamer, vagabond, madman" (Schjeldahl). But if Courbet shared Rembrandt's habit of acting on the canvas, a heightened version of the way we all tend to dramatize ourselves, he also demonstrates here the signifying power of his art. Whatever he may have felt as he produced this painting, it is emphatically not the work of a desperate man. It is rather the work of an artist who knows very well that in art as in drama, representing a passion--even a passion of one's own--calls for a dispassionate sense of control.4 To state only the most obvious point, a man with his hands in his hair could hardly paint this picture.

In paintings such as this, self-portraiture is not so much the art of reproducing one's face in the mirror as of devising and composing signs of oneself that look nothing like what the mirror reflects. In the Renaissance, self-portraits did look mirrored. Two recent studies, for instance, show how often early modern female artists portrayed themselves quite recognizably at work with brushes in hand (Yeazell 4-8). But contemporary self-portraiture is something quite different.

SLIDE 19. Marlene Dumas, The Painter (1994).

New York, Museum of Modern Art.

Painted in 1994 by the South African-born Marlene Dumas, who now works in the Rembrandtian city of Amsterdam, SLIDE 19 displays the artist's five or six year old daughter Helena in the nude at more than life size--the painting is over six feet tall. With her daunting height, her forbidding expression, and her hands dyed red and black, she could almost be taken for an enfant terrible a la Lady Macbeth, fresh from steeping her fingers in the blood and bile of a luckless playmate. But since the painting is called The Painter, it clearly signifies an artist. Overturning the traditional relation between the male artist and the female model, Dumas gives her daughter the main role. "She painted herself," Dumas has said. "The model becomes the artist." But in fact it is Dumas mère who has done the painting here, representing herself--or signifying herself--as a naked little girl fearlessly re-making or woman-handling the world in red and black.

* * *

Self-portraiture differs from autobiography in many ways. Though nothing keeps an artist from re-creating his or her younger self, and thus re-viewing that self in retrospect, nearly all self-portraiture aims to represent the artist's present self, as in the pages of a diary, and not even the ninety-plus self-portraits of Rembrandt deliver anything like a coherent or comprehensive story of his life. But in re-viewing his or her past self, the autobiographer always reshapes it. To see how artists and writers represent themselves, then, is to see how they each crack the mirror paradigm of self-representation. Art as well as literature manifests the impossibility of perfectly reflecting one's life at any moment, the inevitability of self-dramatization, and the periodic necessity of self-signification: portraying oneself in ways that look nothing at all like what the mirror reflects.

NOTES

1See Szczerba. While the MLA Bibliography lists 17 studies nominally dealing with both topics, all but one of them seems to use "self-potraiture" as a metaphor for purely verbal self-representation.

2An earlier, much shorter version of this paper has appeared as "Cracking the Mirror: Self-Representation in Literature and Art,” Queen's Quarterly 115 (Winter 2008): 2-21. My thanks to the editor for allowing me to use some of this material again.

3"Awaking with a start" is a dangling modifier made to seem grammatically dependent on "waves" rather than the speaker, "I." But the grammatical confusion is poetically effective. It suggests the speaker's psychic confusion as he suddenly awakens to see the waters heaving as if they too had suddenly awakened.

4See Joshua Reynolds on De Fresnoy's Art of Painting: "the mind thus occupied [in painting a passionate figure], is not likely at the same time to be possessed with the passion which he is representing" (qtd. Montague, Expression of the Passions 6). See also Francois Ricoboni on drama: "if one is so unfortunate as to truly feel that which one is expressing, one is in no state to act" (L'Art du Theatre [1750], qtd. Montague 53).

WORKS CITED

Alberti, Leon Battista, On Painting, trans. John R. Spencer. Rev. ed.

New Haven: Yale UP, 1966.

Augustine, Confessions, trans. F.J. Sheed.

New York: Sheed and Ward, 1942.

Beloff, Halla. "Rembrandt's Impression Management," Rembrandt by Himself 25-33.

Borges, Jorge Luis. “Borges and I,” in Borges: A Reader: A Selection From The Writings of Jorge Luis

Borges, ed. Emir Rodriguez Monegal and Alistair Reid

(New York: E.P. Dutton, 1981): 278-79.

Byron, Lord. Childe Harold's Pilgrimage [CHP], in Byron, ed. Jerome J. McGann

(New York: Oxford UP, 1986): 19-206.

Chapman, H. Perry. "Rembrandt's Fashioning of the Self, " Rembrandt by Himself 19-21.

Goffman, Erving. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life.

Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Social Sciences Research Centre, 1956.

Lessing, G.E. Laocoon: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry, trans. Edward Allen McCormick

McCormick (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1984).

McGann, Jerome J. Fiery Dust: Byron’s Poetic Development.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968.

Montague, Jennifer, The Expression of the Passions: The Origin and Influence of Charles Le Brun’s

“Conférence sur l’expression générale et particulière.”

New Haven: Yale UP, 1994.

Pamuk, Orhan. Istanbul. New York: Knopf, 2005.

Rembrandt by Himself. (Glasgow: Glasgow Museums and Galleries, 1990.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques, The Confessions . . . . , trans. Christopher Kelly,

ed. Kelly, Roger Masters, and Peter G. Stillman.

Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1995.

Szczerba, Lisa, “The Aesthetics of Self-Representation: Portrayals of Pregnancy and Childbirth

in Autobiographical Film, Self-Portraiture, and Literary Autobiography,”

New York University Dissertation Abstracts International, Section A:

The Humanities and Social Sciences 65:11 (May 2005): 4074.

Schjeldahl, Peter, “Painting by Numbers: Gustave Courbet and the Making of a Master,”

New Yorker, July 23, 2007.

Wetering, Ernst van de, “The Multiple Functions of Rembrandt’s Self-Portraits,”

White and Buvelot 10-17

White, Christoper, and Quentin Buvelot, eds. Rembrandt by Himself:

Catalogue to the National Gallery Exhibition, London: National Gallery Publications, 1999.

Wordsworth, William. The Prelude 1799, 1805, 1850, ed, Jonathan Wordsworth, M.H. Abrams, and Stephen Gill.

New York: Norton, 1979.

Yeazell, Ruth Bernard, “Painting Herself,”

The New York Review of Books, 69:8 (May 12, 2022): 4-8.