CHAPTER 8. Dartmouth Undying: A Tale of Pearls Thrown Away, Two Murals, and the Wheelock Succession

Men of Dartmouth, give a rouse

For the college on the hill

For the Lone Pine above her,

And the loyal sons who love her.

Give a rouse, give a rouse, with a will!

For the sons of old Dartmouth

The sturdy sons of Dartmouth,

Though 'round the girdled earth they roam,

Her spell on them remains;

They have the still North in their hearts,

The hill winds in their veins,

And the granite of New Hampshire

In their muscles and their brains.

Richard Hovey, Class of 1885, "Men of Dartmouth"

Let me start by forestalling your suspicions. Lest you read my title as the slyly ironic headline of what will turn out to be a savage takedown of the Big Green and / or exposė of all the granite rocks in the brains of Dartmouth men, I must first assure you that essentially, this will be a love letter to the college that has so generously supported and nurtured both my teaching and my scholarship for most of my life. But not every sentence here will shed sweet light on the college. Since lovers proverbially quarrel now and then, I have had more than one lover's quarrel with Dartmouth, as I will explain in due time, and I will pull not one of my punches.

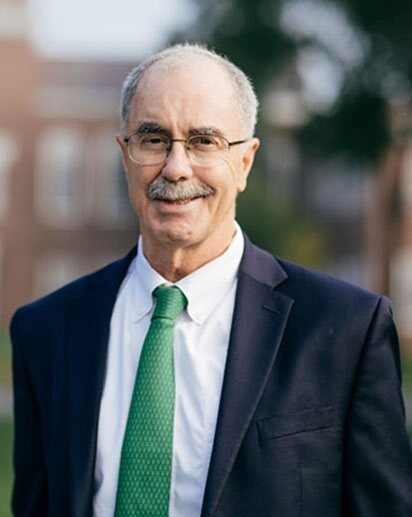

When I joined the Dartmouth English Department as an Assistant Professor in the fall of 1965, I was one of five white males joining a department of approximately 20 other white males. But just as the men of both the title and the opening line of Hovey's "Men of Dartmouth" have long since become an alma mater starting "Dear old Dartmouth, give a rouse," that was the last flood or freshet of all-white-male recruitment, and the Dartmouth English Department now--in 2023-- looks dramatically different from the one I joined in 1965. By my count, its white males have shrunk to 14 even as the total number has grown to more than 30, including 10 white women, 3 Black women, one Black man, 3 Asian women, and one Native American woman.

Unfortunately, however, this diversity of gender, color, and ethnicity in the English department faculty has precipitated a major shrinkage in the number and stature of authors that English majors are required to study. While courses on nearly all major authors are available to majors, it is quite possible to complete the major with no more than a smattering of courses from various periods. Required courses are so few that English majors can complete all requirements without, for instance, reading so much as a single line of Shakespeare or of Milton--two of the greatest giants of the English literary tradition. It is even possible to take a course on English Romantic Literature without reading a single line of Lord Byron.

This way of treating the canonical writers and texts of English literature is clearly driven by a woefully misguided premise: to make way for authors of different colors, genders, and ethnic identities. We must jettison most if not all the dead white authors and works once considered indispensable to the English major. For the folly of playing this zero-sum game--where every white male must be simply replaced by a non-white author of any other gender or ethnicity--becomes obvious once we reckon with Chinua Achebe's admission that he overstated his attack on the racism of Conrad's Heart of Darkness, that Conrad's novella actually fed the imagination of Achebe's 14-year-old Nigerian self and thus helped to shape the writer that eventually created Things Fall Apart.

I will pursue this point more fully in the next chapter. For now I wish to review the recent history of Dartmouth in light of its hiring and firing practices, its craven banishment of the Hovey Grill murals, and its vaunted line of presidents in the Wheelock Succession.

In the early 1970s, the first major step we took to diversify the all-male English faculty was to hire a senior female scholar named Blanche Gelfant. Having already made her name with a pioneering study of The American City Novel (1954), she was a thoroughly seasoned specialist in 20th century American literature by 1972, when the first crop of fully matriculated women students--about 250 that year-- made Dartmouth officially co-educational for the first time in its long history. At Dartmouth Blanche proved herself a remarkably productive scholar as well as a highly engaging and informative teacher. In 1995, after producing books ranging from Women Writing in America: Voices in Collage (1984) to Cross-Cultural Reckonings, she was awarded the Jay B. Hubbell Medal for lifetime achievement in American literary scholarship.

In terms of distinction, Blanche's most obvious successor in the department now is Colleen Boggs, whose voluminous publications include three major books on 19th-century American transnationalism, bestiality, and the Civil War as well as articles in PMLA and other leading journals. But recruitment to the department and promotion thereafter have long ceased to be simply dependent on academic achievement. Starting in 1978, when I became Chair of the department, decisions on both hiring and promotion to tenure became increasingly pressured by the politics of gender, sexuality, and spousal status.

In January of 1979, for instance, during my first year as Chair of the English Department, I sparked a firestorm by arranging to hire a female candidate who was not the wife of another tenured professor in my department. If that sounds strange, it was strange, because in this year Dartmouth suddenly reversed a longstanding ban on "nepotistic" hiring. While for years the college had opposed the hiring of anyone married to a tenured member of the hiring department, on the very good grounds that such a hiring would be influenced by personal feelings rather than professional criteria, Dartmouth now decided to encourage the hiring of spouses on the patently weak grounds that this would turn our faculty departments into cozy coteries of happily married couples--or something like that. I don't mean to sound heartless, because sometimes both halves of a couple have strong qualifications for two jobs in one department, and I've known such cases at Dartmouth as well as elsewhere. But in my experience, a policy that mandates special preference for spousal candidates is a recipe for trouble.

In our case, the spouse who applied for a job in our department clearly thought that the new policy guaranteed her special treatment, When we hired another woman for the job, the rejected spouse complained bitterly to various deans, who in turn demanded reports on the whole history of our hiring process, and much of that month of January was taken up with putting out fires at more than one fraught department meeting after another. My only consolation was that our hiring of the non-spousal candidate was finally accepted.

Fifteen years later, in the winter of 1994, the tenured members of the Dartmouth English department voted to hire a candidate for reasons that had absolutely nothing to do with his academic credentials--and everything to do with his sexual orientation.

Having decided for the first time to recruit a specialist in literary theory (whether or not the theory was applied to any one author), we had narrowed the candidates to two: Casare Casarino and a gay Cuban poet whose name I have mercifully forgotten. Casarino--headed for a PhD from Duke with a provocative thesis on Melville--gave a truly dazzling lecture on literary theory to the tenured members of the department. By contrast, the Cuban poet fumbled on theory and his thesis on Fielding was at best negligible.

To me and to nearly half the others in the tenured ranks, Casarino was by far the stronger candidate. But perhaps because he had reckleesly cast his lot with the dead white straight male known as Herman Melville, there were eight votes for the gay Cuban poet. And since there were 17 of us voting, we needed one more vote to break the tie.

It came from a Shakespeare specialist who had published two books and taught quite successfully during his almost 30 years in the department. But his vote had absolutely nothing to do with the academic credentials of either candidate. To this day and moment I can remember his exact words. "I'm the only gay man in this department now," he said, "and I'd like some company." That's how we wound up rejecting Cesare Casarino, who went on to a career of singular distinction at the University of Minnesota, where his books include Modernity at Sea: Melville, Marx, Conrad in Crisis. (U of Minnesota P 2002). Meanwhile, the gay Cuban poet lasted only one year.

Just as the English Deparrment thus rejected a superbly qualified candidate for purely non-academic reasons, the Dartmouth College administration has likewise fired some superbly qualified candidates for tenure who have come up from within its ranks. So let me tell you about some of the more remarkable pearls it has thrown away.

In May of 1981, during my last year as Chair of the English Department, the Dartmouth CAP (Committee Advisory to the President) voted down tenure for Jay Parini, whom the English Department had recommended by means of a long letter from yours truly. Besides teaching effectively, Jay had already published more than most other candidates for tenure.

There was just one problem. Besides his first book of poetry (Singing in Time) and Theodore Roethke: an American Romantic (1980), Jay had also published The Love Run (1980), a racy novel about a sexual triangle involving two Dartmouth undergrads and a rough-hewn townie. Since the novel was written for cash rather than academic advancement and seemed likely to alarm the CAP, I told Jay that I would keep it out of departmental deliberations on his case and I even got the Dean of the Faculty to promise that it would play no part in Jay's case when it came to the CAP. But it did, and it did him in.

Though never officially informed, I later learned through sleuthing that before the CAP even started talking about Jay's teaching and scholarship, its members were shown a stack of letters from loyal Dartmouth alumni outraged by Jay's fictional desecration of their beloved Big Green. So in spite of the deans' promise, Jay was doomed, for reasons that I all-but-teased out of President John Kemeny in late May of 1981, when I arranged to meet him along with my incoming successor, a medievalist named Alan Gaylord.

Together we reminded the president that both the Dean of Humanities (Tim Duggan) and the Dean of the Faculty (Hans Penner) had agreed that Jay's The Love Run would play no part in the CAP's deliberations on his case. So John, we asked him, how did Jay come to get sacked? Since the tenured faculty of the English Department had recommended him for tenure, and since I myself as chair had laid out the Department's case for his promotion, what was the problem? Most important: did the Dean of the Faculty keep The Love Run off the table, as he had promised?

The answer of course was no, but Kemeny couldn't bring himself to say that openly. All he said was that when the case was opened for discussion, the conference table was quite literally loaded with such "a huge pile of evidence" that it precluded any further discussion and thus closed the case. And the evidence, I gather, was a stack of probably hundreds of letters from Dartmouth alumni outraged by The Love Run and apoplectic at the thought that its author should be granted tenure at their beloved Dear old D.

To see why such "evidence" would override any agreement struck by any Dartmouth administration with me or any other department of the college, you have to realize that Dartmouth's alumni are every year the leading source of its mother's milk. I'm talking not just millions of gallons but billions. As I write these words, Dartmouth has just announced that its new Call to Lead Campaign has already raised a total of 3.77 billion dollars in gifts and pledges from nearly 100,000 donors--overwhelmingly Dartmouth alumni. Doing anything to abrade those mammoth mammaries would be like mastectomy with a hatchet.

But I should perhaps mention one other problem with those ubera: a little lump--or actually a rather formidable figure--known as Leon Black, Dartmouth Class of 1973:

I never taught Leon, but I knew him slightly and still remember his Honors Thesis presentation on masking and unmasking in literature and art, which truly impressed me.

Years later, when Leon's stellar management of the Apollo Fund had made him a billionaire, he and his family generously funded the Black Family Arts Center at Dartmouth, which opened in September 2012 and now houses the offices and studios of the Visual Studies Department as well as exhibition spaces for student art, a movie theater seating 200, and a dramatic atrium: altogether a stellar contribution to Leon's alma mater.

Nevertheless, members of the Dartmouth Community here in Hanover--including many students and faculty members-- have been somewhat troubled by Leon's involvement with Jeffrey Epstein, who was convicted in 2008 of procuring a child for prostitution in Florida, who was later sent to prison on Riker's Island for the sex trafficking of minors in New York and Florida, and who--according to a medical examiner--hanged himself in his jail cell on August 10, 2019 (Wikipedia). Though Leon has denied any involvement with these cases or in the sexual exploitation of underage girls, he does not deny paying to Epstein the rather hefty sum of 158 million dollars , which makes people wonder what he got in return. Financial advice from a man who once taught math without credentials at a Manhattan prep school and later helped embezzlers as well as their victims? (Wikipedia) Hard to say.

But even though local protesters demanded the removal of Black's name from the new Arts Center in 2021 , no Dartmouth administration would ever permit such a gross assault on the ubera of a mega donor. And the local community, after all, could be easily mollified by the assurance that the Black Family Arts Center at Dartmouth is not in fact named for the family of Leon Black at all, but rather for the one and only Black family in the otherwise all-white town of Hanover--a family whose wealth is quite as exceptional as its color.

To return from this long digression to the case of Jay Parini, his threat to the Dartmouth ubera was real and undeniable when Alan Gaylord and I asked President Kemeny why he had been sacked.

Had Kemeny been a little braver, he might simply have reminded us of two things: 1) he was no party to the agreement I had made with the deans who were bringing Jay's case to the college president on behalf of the committee that advised him, and 2) whatever the deans had done or said, the final decision on this case--as on all other candidates for tenure--was his alone to make. But since John couldn't bring himself to say that (he wasn't always as tough as we thought), he equivocated. Notice I didn't say lied.

And finally, what did he thus throw away when he sacked Jay?

Aside from producing 30-plus books of poetry, fiction, non-fiction, Biblical fiction, major biography, and literary criticism, Jay Parini has also seen five of his books made into films or slated for imminent production, including Michael Hoffman's 2009 film of The Last Station: A Novel of Tolstoy's Last Year (1990),which won a Golden Globe Best Actress for Helen Mirren and GG Best Screenplay for Hoffman.

The second pearl Dartmouth threw away--Paul Moravec-- was arguably just as precious as the first.

Though I first met Paul only after he joined the Dartmouth Music Department in 1987, the first thing we discussed were his parents, Vince and Jan, both of whom--by a strange co-incidence-- I had known in the summer of 1948, when--at age 9--I was one of a bunch of Junior House kids they supervised at North Woods Camp in New Hampshire--nine years before Paul was born in Buffalo, New York on November 2, 1957.

By the time Paul got to Dartmouth thirty years later, he had won the Prix de Rome and studied at the American Academy there after graduating from Harvard. He had also received the Master of Music (1982) and Doctor of Musical Arts (1987) in composition, both from Columbia University (Wikipedia).

When he came up for tenure at Dartmouth in 1996, my sources tell me, he was resoundingly endorsed by three different constituencies: his students, his fellow musicologists, and his fellow composers. He was also endorsed by a senior member of the Music Department named Charles Hamm. Within that department, he was opposed by just one other senior member who is now dead and whom I will mercifully designate Unnamed Senior Member (USM). Reportedly jealous of Paul's rising fame (hi there, Signor Othello!), USM set out to sabotage Paul by soliciting a negative letter from one of the outside "readers" of his record. I must admit that I cannot verify that statement, and that when I posed it privately to President James Wright after learning that Paul had been terminated, he of course declined to comment in any way except to say that CAP deliberations were wholly confidential. But to the best of my knowledge, Paul was done in by the jealousy of USM.

And what did Paul do after leaving Dartmouth? Besides becoming a University Professor at Adelphi University on Long Island, New York, he won the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 2004 for his Tempest Fantasy, and he has composed two operas: The Letter (2009) and The Shining (2016). Also, even as I write these words in late January 2024, the Virginia Opera is about to stage his Sanctuary Road, a choral work based on the writings of William Still, a black abolitionist who helped nearly 800 enslaved African Americans escape to freedom via the Underground Railroad,

Dartmouth, dear old Dartmouth, do still think you should have thrown this pearl away?

To these two pearls I feel bound to add a third whom Dartmouth never terminated but also never hired as a full-time member of the Dartmouth faculty. Instead it kept him dangling on a series of temporary appointments--like a string of pearls hung from the back of a closet door.

Nancy and I first met Laurence Davies and his vivacious wife Geraldine in the fall of 1969, when he had just been appointed as a Visiting Instructor in the Department of English for three years. Ebullient and Welsh (like Dylan Thomas) as well as instantly engaging, Laurence was also remarkably seasoned for his twenty-six years. Besides holding an Oxford BA, he had also spent four years teaching in Melbourne, Australia, had just won a Woodrow Wilson International Fellowship for the years from 1969 to 1972, and was well on his way to a D. Phil at the University of Sussex, where his dissertation on "R. B. Cunninghame Graham and the Concept of Impressionism" (1972) would later become his first book, co-authored with Cedric Watts: Cunninghame Graham: A Critical Biography. Published by Cambridge University Press in 1979.

Though by then he had left Dartmouth for other teaching jobs, I strongly encouraged him to return, which he did from 1977 to 2005 as Research Associate Professor of Comparative and English Literature and then--in 2007-- as Visiting Professor of Comparative Literature. During all these years he taught hundreds of students who--so far as I could tell--hugely admired him, and he also supervised far more Honors theses than I did because our very best students knew he was the best--that for sheer range of mind and infectious exuberance on just about any topic you could name he was unbeatable.

And all this time too, he was making himself one of the world's leading authorities on Joseph Conrad. With Frederick Karl and several others he edited in nine volumes The Collected Letters of Joseph Conrad (Cambridge UP, 1983-2007). adding a volume of Conrad's Selected Letters in 2015. Beyond meticulously transcribing Conrad's handwriting, exhaustively annotating the letters and identifying their recipients, he has introduced each volume in a style whose verve, warmth, flair, and circumspection make it altogether captivating. He is among the small handful of academic writers I know whose prose is simply a joy to read.

Having also published about 30 articles on Conrad, plus a few others on Ford Maddox Ford and others, he is now President of the Joseph Conrad Society, UK.

Yet during all the years he taught at Dartmouth--a total of 32, as I add them up--Dartmouth never saw fit to even put him on the tenure track--let alone grant him tenure.

So all I can do for this polymathic scholar, inspiring teacher, legendary mycologist, delightful storyteller and dear friend is to regret that Dartmouth slighted him for so many years and to grant him tenure here--in these pages--so long as anyone may care to read them.

Spring is the season for mayhem. In the spring of 2013, while the city of Boston was rocked by two actual bombs thrown near the finish line of its famous annual marathon, Dartmouth College ended up reeling from the impact of rhetorical bombs.

On Friday, April 19, with all of Boston under lockdown while police closed in on the surviving marathon bomber suspect, Dartmouth welcomed prospective members of next fall's entering class -- "prospies" -- with a program called Dimensions: an official welcome to the Class of 2017, a rousing salute to the class itself and all the "diverse experiences" that Dartmouth will offer them. But around 10:30 that night, just as Boston was celebrating the capture of the suspect, the opening of a show staged for the prospies was hijacked by a small band of student activists shouting that "Dartmouth has a problem" -- a problem with homophobia, racism, sexism, the grossly inadequate reporting of sexual assault and, for good measure, the evils of capitalism.

The vocal bomb thus detonated by the activists soon provoked a volley of online firecrackers. Starting in the wee hours of the day after the protest, a Dartmouth message site called bored@baker featured anonymous comments such as "wish I had a shotgun, would have blown those hippies away" and "it's women like these who deserve to get raped."

In response, Dean of the College Charlotte Johnson publicly deplored the harassment of the protesters, insisting that "threats and intimidation -- even if made anonymously or online -- ... (are) never justified." More dramatically, the Dartmouth administration staged its own version of the Boston lockdown by cancelling classes on April 24 so that all members of the Dartmouth community could gather to discuss its "commitment to debate that promotes ... the value of diverse opinions."

But two days later, Steve Mandel, chairman of Dartmouth's board of trustees, issued a campus-wide email that seemed to find the shouts of the protesters just as objectionable as the words of their detractors. "Neither the disregard for the Dimensions Welcome Show nor the online threats that followed," he wrote "represent what we stand for as a community." Both cases, then, may be subject to "disciplinary action."

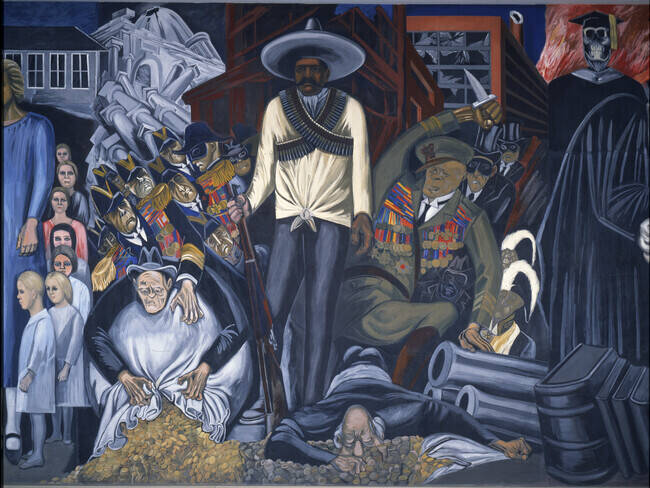

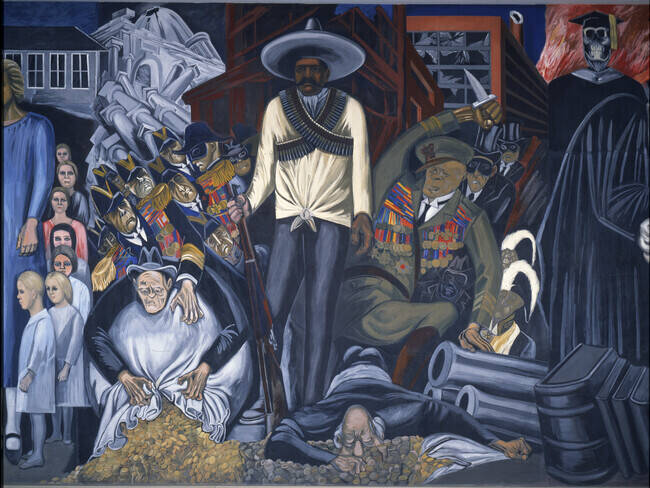

But let's view this episode in the light of two large murals. At least part of what Dartmouth stands for as a community has long been represented by one of them: a sequence of frescoes that drew howls of dismay from Dartmouth alumni when they were first unveiled in 1934. Though it has just been designated a national historic landmark, José Clemente Orozco's Epic of American Civilization -- painted in what is now called the Orozco Room of Dartmouth's Baker Library -- gores the ox of traditional American pieties with a trenchancy that makes the shouts of the Dimensions protesters sound like the cooing of doves.

Besides showing how Christianity helped to destroy the indigenous populations of the Americas rather than "saving" them, as Dartmouth's founder Eleazer Wheelock set out to do in 1768, Orozco's mural savages American capitalism. In one of its panels, a Zapata-like revolutionary proudly defies the rapacity of Yankee capitalists bent over like rooting pigs -- greedily clutching vast bags of coins with cannons and beribboned generals stacked up around them:

It is hard to imagine a fiercer attack on the unholy alliance of money and guns that has shaped so much of the history of U.S. involvement in Latin America. And it is almost as hard to imagine why Orozco himself was not promptly disciplined for assaulting the values of the Dartmouth community -- or at least of the many alumni who wanted the murals whitewashed away.

To his great credit, Dartmouth's President Ernest Martin Hopkins refused to hide them, and to this day they remain to exemplify one face of the college. Fearless of debate and dissent, Dartmouth College not only tolerates but features a searing critique of the very values on which the college was founded and on which America traditionally stands.

But three years after Orozco completed his project, the college commissioned a Saturday Evening Post illustrator named Walter Beach Humphrey (Dartmouth class of 1914) to produce a very different set of murals in a dining room that came to be known as the Hovey Grill. Painted to illustrate "Eleazer Wheelock," a drinking song by Richard Hovey, the Hovey murals have since been found so scandalously racist and sexist that they were moved off campus in September 2018. Fortunately for history, however, they are still available online:

"Oh, Eleazar Wheelock was a very pious man;

He went into the wilderness to teach the Indian,

With a Gradus ad Parnassum, a Bible and a drum,

And five hundred gallons of New England rum."

Fill the bowl up! Fill the bowl up! Drink to Eleazar, / And his primitive Alcazar, Where he mixed drinks for the heathen in the goodness of his soul."

"The big chief that met him was the sachem of the Wah-hoo-wahs;

If he was not a big chief, there was never one you saw who was."

"He had tobacco by the cord, ten squaws, and more to come, But he never yet had tasted of New England rum."

"Eleazar and the big chief harangued and gesticulated;

They founded Dartmouth College, and the big chief matriculated.

Eleazar was the faculty, and the whole curriculum

Was five hundred gallons of New England rum."

Painted to illustrate a drinking song written by Richard Hovey (class of 1885), the Hovey Grill murals salute Dartmouth's founder for allegedly trading 500 gallons of rum for a tract of Native American land and thus introducing its occupants to the joys of college life.

The murals depict Wheelock pouring a golden stream of rum from a large silver bowl for a partying crowd of would-be native Americans. They include several bare-breasted young women (one of whom is trying to read a book upside down), a feather-crowned "brave" whose pale bare muscular chest sports a fresh green Dartmouth D, and -- shaking Wheelock's hand -- "the Sachem of the Wah-hoo-wahs," a tribe concocted from the now-banned Dartmouth "Indian yell."

This is the other face of Dartmouth: lusty, hard-drinking, strenuously heterosexual, and all too eager to turn native American peoples into a metaphor for a far-from vanished breed: the animalistic, hypersexed, beer-guzzling version of the Dartmouth male. In other words, the Hovey murals represent Eleazer Wheelock showing native Americans -- the aboriginal prospies -- how to get bombed.

In the late seventies, Dartmouth belatedly realized that given its original mission to educate native Americans, it ought to treat them with respect and also, not incidentally, treat women -- all women -- as something more than sexual playmates for Dartmouth men. As a result, the Hovey murals were eventually hidden behind solid doors and then moved off campus entirely, though they can still be found online at the website of the Hood Museum. What can never be fully suppressed, however, is the carefree racism and sexism they displayed -- both of which resurfaced, in variant strains, right after the protests made at the Dimensions show.

Dartmouth, in other words, is a place of two murals, one wide open and the other hidden. But to understand its own history, the Dartmouth community must reckon with both.

THE WHEELOCK SUCCESSION

In its own version of what the Roman Catholic Church has long called the Apostolic Succession from St, Peter, the punning petrus (rock) on which Christ founded the church, to the embattled Pope Francis of our own time, Dartmouth cherishes the Wheelock Succession, the line of Dartmouth presidents stretching from its first one, Eleazer Wheelock, who founded the College in 1769, to Sian Beilock, the first woman president Dartmouth has ever had, who took office on July 1, 2023.

This is my brief survey of the presidents who served Dartmouth from 1965, when I joined the Dartmouth faculty, to 2024, when I write these words.

When I first started teaching at Dartmouth in 1965, I was known as a fearsome grader because I didn't believe in grade inflation. As the years passed, I graded somewhat less harshly, awarding many more A's, for instance, especially for students who took my seminar on Joyce's Ulysses, because they really earned top grades--as did the Honors students I supervised, above all Laurel Smith Newby '93, who wrote a brilliant study of familial ghosts in Ulysses.

All this is prelude to the cheekiest move you can imagine: I'm going to grade and assess each of the Dartmouth presidents I've known since 1965. I judge them primarily for their commitment to the humanistic values I have always pursued in my own work, together with their capacity to appreciate and articulate a comprehensive vision of how the arts and sciences can work together to educate young men and women of all colors, creeds, ethnicities, income levels, and genders, so long as they have the capacity and the willingness to learn at the highest level of effort. For the most important key to success in life itself is my three word motto: never stop learning.

But since I also realize that the fund-raising and courting of Dartmouth Alumni has become a crucial part of every president's job; I have consulted a man I consider a wholly reliable spokesperson for the alumni: Wayne LoCurto, Class of 1966, who came here on scholarship in 1962, who remains profoundly grateful to Dartmouth for setting him on a path to great success in business, and who not only served on the Alumni Council from 2008 to 2011 but has also closely followed the actions of the council and the Board of Trustees for many years. Though we belong to different political parties, we share a profound admiration for this college, which surely stands at the very top of U.S. colleges wholly committed to what John Dickey so rightly called "the liberal and liberating arts."

Now: on to the grading!

JOHN SLOAN DICKEY, 1945-1970

Just about all I have to do with John Sloan Dickey, whose 25 year presidency(!) overlapped with my first five years at Dartmouth (1965-70), is to quote Wikipedia:

John Sloan Dickey (November 4, 1907 -- February 9, 1991) was an American diplomat, scholar, and intellectual. Dickey served as the 12th President of Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, from 1945 to 1970, and helped revitalize the Ivy League institution.

There is simply nothing to fault here and everything to praise--especially when you add his legendary rapport with Dartmouth students, starting with ghost stories for newbies at the Mount Moosilaukee lodge and reaching out to Dartmouth Alumni all over the world, And I will never forget that in the nearly last year of his presidency, John Dickey found the time to send me a handwritten letter congratulating me on the publication of my first book, Wordsworth's Theory of Poetry.

GRADE: A resounding A+. John Dickey set the standard against which every one of his successors can and should be measured.

JOHN KEMENY, 1970-1981

Having just now decreed that John Sloan Dickey set the standard by which all his successors should be measured, I now realize that I have led with my chin, for younger generations of Dartmouth alumni might well ask why Dickey himself should not be measured against current standards of diversity and inclusion. How many black students, for instance, were admitted to Dartmouth on his watch? How many women? And given the history of antisemitism at Dartmouth , how many Jews?

Though I strongly suspect the answers in each case range from zero to damn few, I can tell you this: it was not until 1980 that the English Department--while I was chair of it--recommended its first Jewish candidate for promotion and tenure: a dynamite lecturer and brilliant scholar named David Kastan. (He has since left for professorships at Columbia , Yale, and Hong Kong, where the Kastan Chair has just been established.)

But in 1953, a full 27 years before the English Department did this, John Dickey approved a full professorship for a 27-year-old mathematician who--interrupting his undergraduate years at Princeton-- had worked on the Manhattan project at Los Alamos in 1943, had since earned a PhD in math at Princeton in 1949, and was then working there under Albert Einstein. Two years after joining the Dartmouth Math Department Kemeny became its chairman, and held this post until 1967.

All this is to say that John Dickey knew John Kemeny was a comer, and did not let anything like antisemitism thwart his determination to catch a rising star for dear old D.

Nevertheless, I have no doubt that when Kemeny became President of Dartmouth, not all alumni were thrilled, for unlike John Dickey, the very embodiment of good old-fashioned white Anglo-Saxon Protestantism, Kemeny had been born in Budapest, Hungary, and raised as a Jew there until 1940, when the adoption of the second anti-Jewish law in Hungary became imminent. At this point his father took the whole Kemeny family--including 13-year-old Janos-- to the United States.

Unlike those xenophobic and / or anti-Semitic alumni, however, I have two strong reasons for considering John's background an asset. First of all, I count among the dearest of my Dartmouth colleagues a half-Jewish native of Budapest named Steven Scher, whom I fondly recall in Chapter 6. Secondly, the fictional protagonist of James Joyce's Ulysses, which has long been my favorite novel, is a Dubliner of Hungarian Jewish extraction named Leopold Bloom.

Since I never had more than a few brief conversations with Kemeny, I regret that I never even thought to ask him about Steve Scher, who had spent the first 18 years of his life under first the Nazis and then the Soviets until leaving Budapest in 1956. Since Steve himself joined the Dartmouth faculty as a Full Professor in 1974, when he was 38, just as John had joined it as a Full Professor in 1953, when he was 27, they would have had much to talk about--and in their native tongue!

I also regret that I never asked Kemeny about Leopold Bloom, whom he must at least have heard of, but whose command of mathematics was hazy at best:

He halted before Dlugacz's window, staring at the hanks of sausages, polonies, black and white. Fifteen multiplied by. The figures whitened in his mind, unsolved: displeased, he let them fade. (Ulysses, Chapter 4)

Yet whether or not John Kemeny was ever seriously interested in the humanities, let alone the borderline innumerate known as Leopold Bloom, he was still a towering academic figure: an inspiring teacher, a commandingly lucid speaker who filled Spaulding Auditorium when he came back to report on what he found at Three Mile Island after the nuclear meltdown there in late March 1979 ("the biggest Tinkertoy you have ever seen in your life"), a prolific author of books on mathematics and computing, a pioneering minter of "basic" computer language, and a founding father of four-year co-education at Dartmouth, which formally began under his watch in 1972.

He could also talk with ease to just about anyone from major donors to students of all kinds. On one occasion when I found myself standing near him among a small group of young Black women, I scarcely knew what to say to them, but John had them chuckling appreciatively almost at once.

He also had an endearingly well-padded ego that sometimes expressed itself in his singular Hungarian style, with his stubbornly mittel-Europa way of turning all Ws into Vs. When he was still Chair of the Math Department, a colleague named Reese Prosser burst into his office one day to celebrate the news that Dartmouth had just got funding for a brand new chaired professorship in mathematics. "Now." said Reese, "we can go out and hire a really great mathematician." "Vull actually, Reese," said John, " it voss thought that I vould occupy that chair." Kemeny was truly a master of the passive--or dare I say passive-aggessive?--voice.

In any case, I admired greatly all he did for Dartmouth, and I withhold the very highest grade (A+) only because he was less than fully honest when I asked him how he came to sack Jay Parini.

GRADE A

DAVID McLAUGHLIN (1981-86)

In choosing David McLaughlin to succeed John Kemeny, the Trustees obviously sought to make amends, so to speak, for having subjected Dartmouth to a rank outsider--not just a non-alumnus but a Hungarian Jew. Regardless of his extraordinary distinction in all other ways, Kemeny had never been a true son of Dartmouth, and for the sake of all its loyal Big Greeners, it was high time the College chose one of its own.

How could it possibly do better than David McLaughlin, who could hardly be more Dartmouthian if he had once served as Eleazer's own bowman in his first canoe ride up the Connecticut to found the College. (Yes, I know that story's apocryphal but you get my point, right?)

Here's his bio from the Dartmouth website:

As an undergraduate, David T. McLaughlin epitomized the "Dartmouth Man." A member of Phi Beta Kappa and various student organizations such as Green Key, Palaeopitus, and Casque & Gauntlet, he earned his A.B. in 1954 and his M.B.A. in 1955 at the Amos Tuck School of Business Administration. He served Dartmouth steadily after graduation, joining the Board of Trustees in 1971 and becoming chairman in 1977. Like his predecessor Ernest Martin Hopkins, the fourteenth president in the Wheelock Succession came from a business background.

One other thing oddly not mentioned here: David was also a star football player at Dartmouth--so good that he was recruited by the Philadelphia Eagles, but turned them down to earn an M.B.A. at Tuck.

There was just one little problem with this particular Dartmouth Man. Unlike Ernest Martin Hopkins, he had no real understanding of the life of the mind and the liberating power of the liberal arts.

A further problem is that while he did indeed "come from a business background," as Ernest Martin Hopkins had, he had left something of a mess behind him after running Toro for ten years--first as president and COO and then as Chairman of the Board. But as the New York Times reported on August 30, 2004, he was at least brave enough to take the blame:

When he laid off 325 employees in February 1981 with impending layoffs for about 1,000 more, he said the fault was all his.

He had driven an aggressive expansion in the late 1970s into new products such as flexible-line grass trimmers that were rushed to market, resulting in shoddy workmanship that tarnished Toro's reputation for quality. He courted mass merchants who discounted Toro machines, undercutting hardware dealers on which the company relied to service its lawnmowers and snowblowers. Then it snowed little for two winters, and 350,000 snowblowers sat in Toro warehouses.

Two weeks after the firings, McLaughlin resigned to become president of Dartmouth, his alma mater.

In other words, Mr. Dartmouth threw himself back on the Big Green as a refuge from disgrace and disaster at Toro. But unfortunately, he had not yet fully learned the price to be paid for his aggressiveness, which can be bad enough in business but even worse at a college, which college presidents are meant to lead by inspiration and example, not run like chains of command--or balky snow blowers. (But I must admit that my own Toro push mower, which I must have bought before the advent of "shoddy workmanship" in the mid-70s, actually ran for something like 40 years (!) with the aid of expert yearly servicing by a sweet old guy named Bob Beauchene up at Goodrich Four Corners in Norwich.)

As a man sensitive to public relations (if not so much to the plight of his former employees at Toro), David did not like unsightly things on the Dartmouth Green. So he could not for long tolerate its desecration by the shanty that students erected there to signify their solidarity with the poor Black segregated shanty-dwellers of Soweto in South Africa, and to demand Dartmouth's divestment from the nation's apartheid regime.

Under David's watch on February 12, 1986, therefore, 18 students protesting apartheid were arrested when they refused to vacate the last shanty on the Green, which was picked up with a fork-lift truck by College crews who also used a pneumatic drill to pry the floor out of the ice on the Green.

And David held his apartheid-backing ground in every sense, for it was not until well after he left office--in November of 1989--that the College ended its 11 million dollar investment in South Africa.

Furthermore, he antagonized the Dartmouth faculty by reinstating the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) in order to "open up another avenue of funding," as he told the Christian Science Monitor in 1985.

On this point, though, I actually sided with him, and in fairness I give him full credit for more than doubling the school's endowment, increasing faculty salaries by 43 percent and overseeing new dorms--the McLaughlin Cluster --on the site of the now demolished Mary Hitchcock Hospital.

According to his obituary in the New York Times (see above), he resigned in October 1986 just as the college started a 10-year fundraising campaign, and died on August 25, 2004, while on a fishing trip at a lodge in Dillingham, Alaska.

GRADE B-

As high as I can make it. Sorry, Mr. Dartmouth!

JAMES OLIVER FREEDMAN (1987-1998)

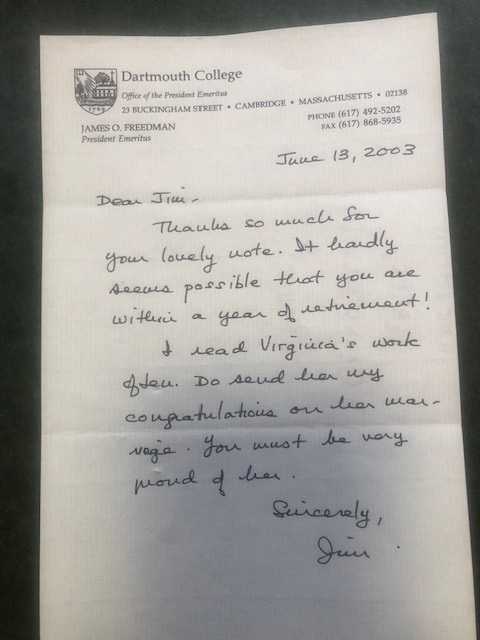

Right up front, I must admit a bias: among all the Dartmouth presidents of my time, Jim was my personal favorite because he not only loved literature but shared my passion for Joyce, attended one of my seminar sessions on Ulysses, praised me for it afterwards as a "master teacher," invited Nancy and me to dinner at the president's house with poets such as Galway Kinnell and Derek Walcott and found the time to send me something like half a dozen handwritten notes such as this one, which not only thanks me for a note of mine but also mentions that he admires the writing of my daughter Virginia

Given all this, you may wonder why I don't simply stop right here and give Jim a resounding A+. So I will tell you exactly why. But first I must comment on the altogether predictable way in which the pendulum of choice has swung back and forth every time Dartmouth appoints a new president: insider, outsider, insider, outsider, insider, outsider, tick and tock. Regular as clockwork.

Case in point: trying to make amends for having chosen a rank outsider--a Hungarian Jew--to follow the great John Dickey, Dartmouth proudly imports a big fat chunk of Grade A Mr. Dartmouth Greenturf which turns out to be (for shame!) largely infected with Roundup--and you all know what that stuff will do to your lawn. (It's now illegal, in fact.) Whoops! So the pendulum swings back, and the Trustees feel perfectly free to choose another outsider--even to the point of placing a bet on yet another Jew. Plus: it turns out this guy is not mittel europa like Kemeny with his V for W accent but rather mittel newhampshire! A grade A striver whose father taught high school English in Manchester, young Jim had sailed through the Ivies--Harvard B.A., law degree at Yale--and had already proven himself a man of presidential timber. After serving as Dean of the Penn Law School, he'd been President of the University of Iowa for five years (1982-1987) when the selection committee came calling. If you want an outsider this time, how could you do any better than this guy?

Well, if you wanted to be a Monday morning quarterback, you could point out that the $25 million dollar laser research center that Jim proudly launched in Iowa eventually fizzled out because even after it was built, it could never attract enough funds to keep it going (Wikipedia). But that was a far cry from the mess that Mr. Dartmouth had left behind at Toro--right?

Plus, Freedman offered something David never had: a genuine love of literature and the humanities that he must have imbibed from his father, just as I had imbibed such a love from mine.

David was so clueless about literature that whenever he had to give a speech, he would pump one of our best Shakespeare specialists--David Kastan--for something of the bard to quote. By contrast, Jim was a voracious reader whose very first speech to the faculty utterly charmed us--especially the humanists like me--because he quoted writers and philosophers ranging (as best as I can recall) from Plato to Albert Camus. It was his way of saying that his chief goal as president to make Dartmouth a place of true intellectual distinction.

Since he also published several books about the value of a liberal education---books such as Idealism and Liberal Education (1996)--he might well be regarded as a true intellectual heir to the liberalizing vision of John Sloan Dickey.

OK so far? But it turns out there was a fly or rather something close to a dead mackerel in Jim's precious ointment. According to Wayne LoCurto '66, he struck many of the alumni as a cold fish. Wayne also tells me that Jim hated fund-raising, which Wayne thinks should be at least half of a president's job.

On that I beg to differ, because one of the biggest Asks ever made in Dartmouth's history--the Ask for the Baker-Berry Library--was made not by any Dartmouth president but by a young man in the development office named Young Dawkins, who--along with his wife--spent five years cultivating John Berry before telling him that he--John-- was going to do "something wonderful" for Dartmouth, and thus elicited Berry's offer to fund the new library, whose ground was broken just before Jim stepped down in 1998. So given their exceptional expertise in the fine arts of fund-raising and Making the Ask, I would not seriously fault any Dartmouth president who left the development specialists to do most or even all of the Asking.

In any case, against Jim's discomfort with fund-raising and gladhanding I set the testimony of a former student whom I have known and deeply respected for many years, According to Paul Hochman, Class of 1986, who was here in the McLaughlin years but closely watched his successor, "Freedman's innate kindness transformed the feel of the Dartmouth community from one of competitive excellence into one that balanced world-class academic standards with social awareness."

And now let's give Jim Freedman credit for what he did -- according to Wikipedia:

President Freedman established or revitalized programs in Latin American, Latino, and Caribbean Studies; Environmental Studies; Jewish Studies; and Linguistics and Cognitive Science. He introduced or restored the teaching of the Arabic, Hebrew, and Japanese languages, founded the Institute of Arctic Studies, and incorporated into the curriculum majors in Women's Studies and African and African-American Studies. During his administration, Dartmouth achieved gender parity in the student body. In the professorial ranks the College led the Ivy League with the highest proportion of women among tenured and tenure-track faculty.

Freedman also presided over the largest capital campaign in Dartmouth's history, the 'Will to Excel' campaign, which raised $568 million, exceeding the original $425 million goal. His administration saw the addition of state-of-the-art buildings for the Computer Sciences, Chemistry, and Psychology, as well as The Roth Center for Jewish Life and the Rauner Special Collections Library. (Wikipedia)

He also took on the Dartmouth Review, that womb of bright young conservatives first fertilized by Jeffrey Hart in the 1960s--with of course the baptismal blessing of William Buckley and his National Review. The sole aim of the Dartmouth Review has been and always will be to harass Dartmouth as much as possible from the right--on the grounds that this would-be bastion of academic liberalism is really nothing more than a Bastille of torture for young conservatives, whose howls of protest--if they're lucky--will lead them on to fame as right-wing conspiracy theorists such as Dinesh D'Souza (aka "distort da newsa"), Dartmouth '81, or the Reigning Queen of Fox Talk Vapidity known as Laura Ingraham, Dartmouth '85 (both Wikipedia).

My favorite story about the Dartmouth Review is about what happened early in its wild career, when Jeff Hart's son Ben tried to dump a pile of copies just outside the office of a Black administrative officer in Parkhurst Hall. During the ensuing fracas (I'm told), Ben felt the teeth of the administrator piercing his right forearm, and promptly went home to tell his father, "Dad, I've been bitten!" Blessed are those who suffer persecution for justice's sake, his father might have told him. But in any case, that's the juicy story of a bleeding Hart conservative.

More seriously, the Dartmouth Review stooped just about as low as any paper could in 1990, when--on Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar--it not only stuck a quotation from Hitler's Mein Kampf into the masthead of one edition, but also printed a drawing of Freedman as Hitler. And it was a full three days before the editor discovered the vicious prank, pulled available copies, and issued an apology (Wikipedia).

Where then do I finally come out on Jim?

A good, decent, thoroughly humane man who did everything he could to make Dartmouth a better place by the best of his own lights. A man who thoroughly shared my love of literature, especially Joyce, and whom I considered a personal friend. A man whose death from non-Hodgkin's lymphoma on March 21, 2006 I mourn to this very day.

GRADE A-

JAMES WRIGHT (1998-2009)

Jim Wright was probably the easiest choice the Trustees ever made. By 1998, when he was nominally competing with other candidates rounded up in a "National Search," he had already served Dartmouth as Associate Dean of the Faculty, Dean of the Faculty, Acting Provost, Provost, and Acting President for a year when Freedman took a sabbatical. Though he was technically an outsider (non-D alumnus) succeeding another outsider (the non-alumnus Freedman) and thus an exception to the tick-tock formula, he had made himself the ultimate insider by the time he was formally installed in the Wheelock Succession.

Now I have a confession to make: for many years I grossly underestimated Jim. Not long after he joined the History Department in 1969, four years after I got here, I told one of his gossipy colleagues that I found him a bit pompous and rather dull, and I'm willing to bet that those words quickly got back around to Jim, and I'm also willing to bet that he never forgave me for them. It has taken me years to figure this out because I'm a very slow learner, but fortunately, 84 years has given me a long time to learn.

Though Jim and I were born just four months apart (I in April of 1939, he the following August), our pre-Dartmouth backgrounds were totally different. As the son of a highly successful Boston doctor, I never had to worry about money. After putting me though a Jesuit High School in Boston and then through Georgetown in the late fifties, and not just paying my tuition plus room and board but also sending me $100 a month as an "allowance" for extras, my father continued this allowance through my graduate school years at Princeton (where I was otherwise funded by a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship), and ended it only after I started my first job as an Instructor in English at the University of Virginia in the fall of 1963. During all this time I never served a day in the armed forces of the U.S., and thereafter got myself deferred by reason of my services to higher education.

Whatever Jim may have known or suspected about all of this, his pre-Dartmouth background could hardly have been more different from mine. While I had coasted from one phase of my life to the next, his ascent was one long series of hard struggles.

About the only thing we both did was finish high school at the age of 17. But in the working-class town of Galena, Illinois, where hardly anyone even thought about going to college, Jim had just two options: go to work--in the mines, or for Kraft Foods, or for John Deere in Iowa, across the river--or join the U.S. Marine Corps. He chose the marines.

But he did not give up on college.

Instead, after serving in Japan during the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis of 1958, he returned to Galena with the idea of becoming a high school history teacher there. To that end, he worked his way through the University of Wisconsin-Platteville with various jobs ranging from janitor to powderman in the local mines--detonating dynamite and then trimming the jagged rocks that remained with a 20-foot iron bar.

And of course he could easily have been satisfied with his BA. But instead he earned a graduate fellowship to the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he studied the political history of the American West and wrote his PhD thesis on populist movements in Colorado. How many other kids from Galena, Illinois had ever even dreamt of doing such a thing? My bet is none.

So when Jim Wright heard--as I strongly suspect he did--that some guy in the English Department thought he was a bit pompous and a bit dull, he may have done a little digging on me. If so, he would have learned that I was a pampered puppy who had never done a day's hard work in my life (let alone powderman), never served in the armed forces of these United States, and never had to worry about money. Who the hell was I to call Jim Wright pompous and dull? He would never forgive me for that, and he let me know it--in so many words-- every time he had the chance to say anything good about what I had done.

When, for instance, the English Department nominated me as the first holder of the Frederick Sessions Beebe Professorship in the Art of Writing in 1997, he summoned me to his office (then Provost), quizzed me about my publications as if I were a perfect stranger, and offered not a word of commendation on the honor I had received. At the little cocktail party after my Inaugural lecture as Beebe Professor, he shook my hand, said nothing about the lecture (which was otherwise very well received), and promptly left. And not long after, when I told him one day that the Teaching Company had invited me to tape a lecture series for them, he said simply, "That's all on the internet now." No Jim, I could have told him. First of all, the TC charges for its lecture courses; they don't just put them out there for free. Secondly, the TC recruits only a very small number of lecturers tracked down by their scouts in response to student recommendations, so getting invited in this way is a tribute to my teaching. But I didn't say that to him--because by then I had begun to suspect that I was still getting punished for the stupid, tactless, arrogant crack about him that I had made to his gossipy colleague years before.

I hope I haven't bored you to tears by writing so much about myself in what is supposed to be an evaluation of Jim. But to judge this evaluation fairly, you need to know exactly who it's coming from. And I can now tell you that it's coming from a man who has finally learned just how much Jim Wright did for Dartmouth, for his students, for the study of history, and above all for the veterans of our foreign wars: men who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, men who (like Jim himself) had few or no viable options but military service after high school, men who might never have gone to college if not for Jim. And against all that, what did his tiny slights to my vanity weigh? Not so much as a feather.

Beyond that, Jim was simply one of the most thoroughly accomplished presidents Dartmouth has ever had. Besides his prolific scholarship (four books on the history of the American West plus one on the history of New Hampshire), for which he once won a Guggenheim Fellowship (something I never managed to do myself), he climbed the ladder of administrative posts at Dartmouth with dazzling rapidity. After co-chairing the ad hoc committee that recommended the creation of the Native American Studies Program, which was launched in 1972, he chaired the Committee on Curriculum and Year Round Education, which has since become a central part of life at Dartmouth.

As president of Dartmouth, he led a campaign that raised more than 1.3 billion--then the largest campaign goal in Dartmouth's history . The new funds supported not just financial aid for more students but also a splendid spate of new buildings such as the Baker-Berry Library, Kemeny Hall, and the Haldeman Center.

Most impressive of all, however, is what Jim did for his fellow veterans--men who, like himself, had enlisted in the armed forces rather than going to college because college was simply unaffordable or otherwise unavailable. Starting in 2005, Jim not only visited wounded veterans in U.S. military hospitals but also raised money for veterans' education and lobbied Congess to help private universities and private colleges (including of course Dartmouth) partner with Veterans Affairs to support veteran students.

After finishing his presidency in 2009, he returned to the writing of history with a laser focus on U.S. veterans--one book on Enduring Vietnam, another on A History of America's Wars and Those Who Fought Them, and a third on War and American Life: Reflections on Those Who Serve and Sacrifice.

Aptly enough, his slew of almost countless awards from this period include the Commander-in-Chief's Gold Medal of Merit Award and Citation at the 2009 Convention of the Veterans of Foreign Wars.

I last saw Jim on a hot, sunny day in late June of 2022, when he and Susan came to a garden party at our house--the first time Nancy and I had ever entertained them, though we had by then become good friends with Susan because we saw her every Sunday morning for the 8 o'clock service at St. Thomas Church. Jim was frail but smiling, said little, but seemed to enjoy himself while mostly seated--a bit precariously!--in one of our white plastic outdoor chairs.

On October 10, 2022, Jim died of cancer at the age of 83.

GRADE: A RESOUNDING A

JIM YONG KIM (2009-2012)

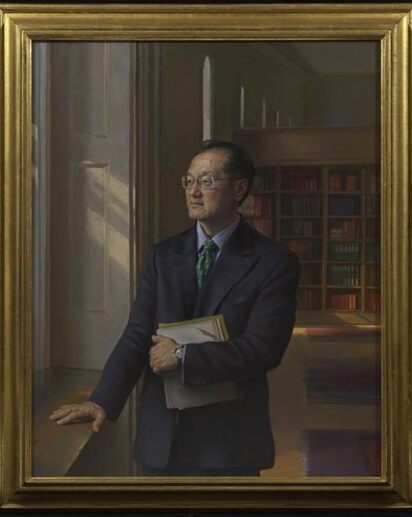

In the rarefied category to which he belongs, I do not know if Jim Yong Kim has any serious rivals among Dartmouth presidents who came between Eleazer Wheelock and Ernest Martin Hopkims. All I can say is that to the best of my knowledge, Jim Kim is the most cynical charlatan ever placed in the Wheelock Succession.

I'm well aware that he dragged behind him--like a bride's great lacy train--a pearl-encrusted record of prior accomplishment. Born in Seoul, South Korea in 1959, he came to the U.S, with his family at the age of 5, grew up in Muscatine, Iowa (where he starred in every possible way at his high school), earned a B.A. magna cum laude from Brown in 1982, an MD from Harvard Medical School in 1991, and a PhD in anthropology from Harvard University in 1993. Furthermore, along with Paul Farmer and several others, he helped to found Partners in Health, which by the early 1990s served over 100,000 people in Haiti by curing tuberculosis patients in their homes at low cost. Kim himself played a leading role in designing treatment protocols and making deals for cheaper, more effective drugs.

So my assessment of him has nothing to do with what he did before becoming president of Dartmouth in 2009, and everything to do with what he did when he got here.

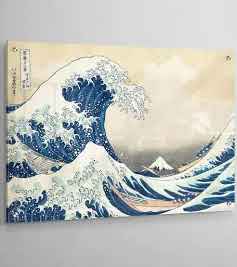

Have you ever seen Katsushika Hokusai's print called The Great Wave off Kanagawa (1831)?

In the fall of 2009, Jim Kim rolled into Dartmouth on a tidal wave of euphoria that evaporated almost as soon as it hit the Dartmouth Green. At first he charmed all the right people by telling them exactly what they wanted to hear--especially when talking to alumni worried about the future of Dartmouth fraternities. Dartmouth fraternities, he smilingly assured them, were famous for turning out leaders!

I had a brief taste of his charm once while standing just inside the door of St. Thomas Episcopal Church in Hanover at the end of a service for a dear friend named Nardi Campion. I think we may have done no more than shake hands, but the charm he radiated felt like a sunlamp--or maybe an acetylene torch.

The charm, it turns out, was composed of equal parts ego and hustler. Quite simply, Jim Kim took the Dartmouth presidency as his stepping stone to the presidency of the World Bank, and he took us for suckers. Though he assured everyone of importance that he was totally devoted to Dartmouth students, reliable sources tell me that most of them had no idea who he was, and according to one member of the Class of 2011, those who did "despised" him:

We knew who [he] was, but not in a good way. We laughed about the $10,000 rewriting of Parkhurst Hall just to run a custom coffee pot, and we cried over the spike in sexual violence against women during his tenure. (Email to author of 2 February 2024)

And here's a snapshot of his ego in action: for the first home football game each fall, Dartmouth players have traditionally chosen one of their number to lead the team out of the dugout by carrying the Dartmouth flag on to the field. But when Jim Kim learned of this while standing in the dugout just before the first home game of 2009, he grabbed the flag from the chosen bearer and took it out on the field himself. Thanks, Jim!

Now let's take a deep dive into his presidency with the aid of a series of interviews that he gave to Irene M. Wielawski | in the fall of 2011 and that were fully reported in the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine of January-February 2012.

During his first year on the job (2009-10), the fallout from the stock market collapse of 2008 forced him to make more than $100 million in budget cuts. But he also launched what are said to be "two ground-breaking initiatives": one to combat binge drinking among Dartmouth students and the other to create the Dartmouth Center for Health Care Delivery Science, which was funded by a gift of $35 million that Kim himself presumably solicited from two non-Dartmouth donors who chose to remain anonymous.

Let's look first at the binge-drinking initiative.

"Almost out of the blue," Kim told his interviewer, "a group of students came to me and said, 'We've heard of this program at Haverford College that seems to be working really well. We're going to do it here.'

"So now we have the Green Team operating at parties across the campus. All we really had to do was create paid jobs for these students to go to parties and not drink and help others who have been drinking."

And that's the binge drinking initiative? Besides, perhaps, increasing the amount of soft drinks consumed at Dartmouth parties, did it reduce the incidence of binge drinking in any way? Did any binge drinkers start binging on Pepsi or Dr. Pepper? We have no way of knowing because Kim doesn't say. He doesn't even tell us how much he paid those party-hopping teetotalers.

A reliable source can, however, contribute one contemporary perspective:

"While President Wright, whom we all adored, had worked to keeped fraternities extant but respectable. President Kim took off the brakes. Binge drinking became immeasurably worse under President Kim, because the college administration was washing its hands of any active oversight over student life, and the fraternities were now running the social scene without any semblance of restraint. Nobody knew what to do, except to drink more. I never saw a Pepsi or a Dr. Pepper outside of a vending machine.

So much for the great binge-drinking initiative!

Now let's examine what I'm sure Jim considers his signature contribution to Dartmouth during the first year of his presidency: the Dartmouth Center for Health Care Delivery Science, for which he singlehandedly raised $35 million--quite a feat of fund-raising, Jim!

While I don't have data on its short-term results, I lately learned that as of right now, Dartmouth College is "self-insured" rather than insured by any outside Health Insurance Company. In practice, this means that Dartmouth is not bound to cover very rare ailments such as the brain disease known as PANS--even though New Hampshire law requires such coverage from all insurance companies doing business in the state. But since Dartmouth took PANS off the CIGNA menu, CIGNA initially denied a claim for PANS treatment in 2022, and the Dartmouth faculty parent of the child who got that treatment would have been out of pocket nearly one-quarter of a million dollars if the parent had not spent hundreds of hours meticulously filling out forms over a period of six months until CIGNA finally apologized and paid up. And this is the kind of service that $35 million dollars' worth of work on Health Care Delivery Science at Dartmouth eventually delivers?

Now let's move on to Kim's management style as revealed in his interview for the DAM. Essentially, he saw himself as a cheerleader who didn't even need to know what his players were doing:

"Part of helping talented people achieve success is just going out and showing my support--that I'm here for them and I'm going to try to solve problems for them. Another part is steering clear of what's not my job. It's not my job to have a gazillion opinions about what Dartmouth faculty should be doing in their research or about the scholarly directions that specific departments choose. This is the crux of American higher education--academic freedom--and it's the reason we've been great for so many decades. Faculty have the license to go in whatever directions they think are important."

So as president of Dartmouth, Jim, all you had to do was beat the drum for your faculty? Regardless of which way they marched? And "academic freedom" means that you don't give a damn what they do--or even how good or how ground-breaking their research and teaching might be? So when you voted on tenure cases--and the final decision was yours alone as president--what were your criteria?

OK, to be fair, you had a reasonable answer for Dartmouth alumni fearful that Dartmouth might sacrifice even a part of its traditional commitment to teaching at the unholy altar of "research" and thus turn itself into--horrors!--Dartmouth University, To those who feared this you said that Dartmouth actually needed to focus on three things: "research, teaching, and engagement with the rest of the world, a mission that I think is also deeply ingrained in the DNA of this place. These three cornerstones of a Dartmouth education are what makes us unique and potentially a model for other institutions of higher education."

Fair enough, Jim, but just what did this mean in practice--especially for the teaching of liberal arts here and specifically of the humanities?

Here too you talked a good game:

"I've come to the conclusion that one of the most important things that any of us can do is contribute to the education of the next generation, to expose them to philosophy and literature and science and Dartmouth's incredible variety of extracurricular activities in a way that forces them to understand who they are in a variety of settings and their responsibility to tackle difficult problems."

Note how "philosophy and literature and science" all fall into the merry-go-round of diversions--along with "extracurricular activities"--to which Dartmouth students are "exposed." Are they expected to study, ingest, or meditate on the philosophical works of Plato, Aristotle, and Kant, or the epic poetry of Milton, say, or pick up just enough to say at a cocktail party, "O yeah! Paradise Lost! I never got past the opening lines!"

Again to be perfectly fair, Kim aimed to do something quite specific for the humanities at Dartmouth. . "We have to fix Dartmouth Row," he told the interviewer, "where the religion, classics, philosophy, comparative literature and language departments are housed." And Dartmouth Row has indeed been rather splendidly renovated. But aside from that, just how and what did Kim think of the humanities at Dartmouth?

Here's part of the answer: in a general way, he saluted the value of "the kind of broad liberal arts education that we offer at Dartmouth."

But his metaphor for the liberal arts is as telling as it is fatuous:

"The College's most generous supporters know that our commitment to the liberal arts is the special sauce of a Dartmouth education."

Have you by chance ever seen the recipe for this sauce? I have. As best as I can recall, it includes a dash of Plato plus a pinch of Homer, a teaspoon of Virgil, and a whole tablespoon of James Joyce's Ulysses. And all to be taken with a full gallon of Dr. Pepper so as to preclude any chance of binge drinking.

But I must admit that Jim Kim saved the very best of his remarks for the end, where he lays out his plans for the future of Dartmouth:

"I am listening for the compelling ideas that I can go out and sell. I can't go to our most faithful donors and say,"Hey, we need lots more faculty, just give us the money." We must present a compelling idea. That's what we're going to be working on, not just in the coming year but for at least the next five years." But of course in much less than one year after this interview, he was gone. And one of the worst things he did was done on his way out in June of 2012.

During the previous fall, I had recommended to the Committee on Honorary Degrees a Professor of Comparative Literature at Princeton named Robert Hollander. Though the HD Committee is generally cool to academic humanists (the committee tends to prefer the rich and or famous), Hollander was extraordinary: probably the world's greatest authority on Dante (he had won a gold medal in Florence for his exhaustively annotated translation of the Divine Comedy), he also pioneered in the digital study of the humanities by establishing the Dartmouth Dante--an invaluable database of otherwise very hard to find commentaries on the DC extending over some five centuries. He had also taught at Dartmouth for several summers. If ever the committee would consider choosing a humanist, it could hardly find a better one--anywhere in the world.

And what did I get in response to my recommendation? Not one word from the committee or from anyone else--let alone Jim Kim. But guess who did get an Honorary Degree that year--at the stubborn insistence of Jim?

His wife, Younsook Lim, a pediatrician who worked at the Dartmouth Center for Health Care Delivery Science during the three years of Kim's presidency--as well as helping him care for their young children. And for that she got an honorary degree?

I will say one more thing about my grade for Kim.

During my first years at Dartmouth in the late sixties, a student who truly trashed a course could be given not just an E, but E "with flagrant neglect." So just to show that I can temper justice with mercy, here is my final, non-negotiable grade for Jim Kim:

GRADE: E

And he's lucky to get it. Let him fade into the shadows of that crepuscular portrait until he disappears altogether from it. Also, a good friend of mine who has long worked for the World Bank tells me that Kim deserves an even lower grade for what he did there from 2012 to 2019.

PHILIP HANLON (2013-2022)

Tick-tock, tick-tock goes the Trustees' clock. Having swung out for yet another outsider who proved a total flop, they swung back yet again to another good old Dartmouth grad, Class of 1977. So here's another man deserving a special superlative. Just as Jim Kim was the most cynical charlatan ever placed in the Wheelock Succession, Phil Hanlon was far and away the dullest--as well as among the most spineless.

Let it be clear that I speak from vast reserves of ignorance about his skills as a mathematician, though I strongly suspect they fall somewhere between the wizardry of Kemeny and the borderline innumeracy of Joyce's Leopold Bloom--with perhaps just a little lean toward the latter.

OK, OK: maybe I'm being a little unfair to this guy, so I should pause for a good hard look at his special strengths and accomplishments before saying more.

For a start, his Dartmouth BA came summa cum laude, which he contrived to earn even while belonging to the fraternity (Alpha Delta) that inspired Animal House--surely no mean feat. Then in 1981 he earned his PhD from the California Institute of Technology with a dissertation titled Applications of the Quaternions to the Study of Imaginary Quadratic Ring Class Groups. Wow! How could I even think of calling this man dull?

And then, after teaching math at MIT and Cal Tech, Phil wound up as Provost and Executive Vice President of Academic Affairs at the University of Michigan, where he also served as the Donald J. Lewis Collegiate Professor of Mathematics. A sterling resume, right? So in 2009, still reeling from the disaster of Jim Yong Kim, the Trustees call this gilded son of Dartmouth home. He will salve our wounds. He will never use us a stepping stone! He will be all for the Big Green, and we will love him to pieces.

But during his presidency, our Big Greener and star mathematician consistently over-estimated the number of students Dartmouth could accommodate, leaving us with an unwieldy surplus of more than two hundred a year. On top of which he had absolutely no understanding of the humanities.

He plainly showed this in the fall of 2012, when he was formally presented to the "Dartmouth Community" at a big meeting held in the auditorium of the Hanover Inn. When asked what he planned to do for the humanities at Dartmouth, he assured the questioner that he was all for the humanities--and then pivoted at once to entrepreneurship, which shortly became his pet project.

OK, OK, I know from Dartmouth's website that Phil "encouraged innovation in scholarship and teaching," that he "launched initiatives to build interdisciplinary strength around global challenges," that he "expanded opportunities for experiential learning, and initiated new seed funding programs to support cutting-edge research and creative endeavors." I also know that he "launched the Irving Institute for Energy and Society, established the DEN Innovation and New Venture Incubator (now known as the Magnuson Center for Entrepreneurship) and led the expansion of the Thayer School of Engineering." And that he "created the Society of Fellows, an interdisciplinary community of post-doctoral scholars dedicated to the integration of research and teaching."

And what a wonderful bean counter he was! "Committed to reining in the costs of higher education, Hanlon maintained fiscal rigor throughout his presidency, establishing an annual institution-wide reallocation process while holding tuition increases to the lowest levels since the 1970s." And a boffo fund raiser too!--since he "oversaw record levels of giving, raising more than $3.7 billion with 60% alumni participation in the Call to Lead campaign, the most successful in Dartmouth's history."

AND THERE'S MORE, AS PHIL'S CUP RUNNETH OVER.

"Under Hanlon's leadership, Dartmouth also launched a comprehensive set of initiatives designed to combat high-risk behaviors while building a more diverse, inclusive, and equitable environment for students, faculty, and staff. Among them were Moving Dartmouth Forward (2015), Inclusive Excellence (2016) and, most recently, the Campus Climate and Culture Initiative (2019) aimed specifically at creating a learning environment free from sexual harassment and the abuse of power. These three interlocking initiatives formed a broad-based program to ensure that behaviors and relationships in all contexts on campus are consistent with Dartmouth's values."

BUT did he have any idea of how to integrate the study of mathematics with all the rest of the liberal arts, above all the humanities? Did his thinking on this question ever move beyond the super-specialized terms of his doctoral thesis, which I'll bet you find just as incomprehensible as I do? Judge for yourself, my friends:

"As a mathematician, Hanlon's academic research is focused on probability and combinatorics, the study of finite structures and their significance as they relate to bioinformatics, computer science, and other fields. A dedicated teacher-scholar, President Hanlon is a current member of the faculty and teaches in the mathematics department at Dartmouth."

Do those "other fields" include such things as history, philosophy, and literature? If not, why not?

I doubt very much that he could tell me, because no one I know ever had a conversation with him. And though I gather that he faithfully attended all Dartmouth football games like the loyal Big Greener we all thought he would be, my sources tell me that it was useless to sit beside him because all he did was crunch numbers on his cellphone. He had nothing to say to anyone else.

Furthermore, as Randall Balmer has reported, Hanlon grossly mistreated James Tengatenga, the Anglican bishop of Southern Malawi, in the summer of 2013. Not long after the bishop accepted Hanlon's offer to make him both chaplain and dean of the Tucker Foundation, Hanlon rescinded the offer.

In doing so, Balmer reports, Hanlon rejected a man who would have brought to Dartmouth just the kinds of "moral authority" that the selection committee sought in its new dean: the moral courage to condemn such things as racist graffiti and sexual assault on campus. (My sole source for complete information on this case is Randall Balmer, Professor of Religion at Dartmouth, who was on the selection committee that chose the bishop.)

"When James Tengatenga's application arrived," Balmer writes, "we recognized that he was an extraordinary candidate, a seasoned administrator who was both an academic and a cleric, someone who had confronted injustice and bigotry and corruption since he was a teenager growing up beneath the thumb of a white supremacist regime in Africa." He had also "advocated for human rights during his entire adult life," working to eliminate HIV/AIDS, sex trafficking and violence against women." But he had also "lived in fear for his life for the [previous] decade because he dared to challenge the corruption of Malawi's regime."

Shortly after the selection committee unanimously recommended the bishop, the provost and president approved the offer, and the bishop accepted it.