CHAPTER 6. TRIPPING MY WAY TO ONE UNFORGETTABLE PARTY

For non-radical tenureds like me as well as lamestreamed tenured radicals, one of the juiciest perks of an academic job is the number of trips you get to take on the dime of your institution or of any other institution that might ask you to speak at a conference or colloquium of some sort or even give the keynote speech. Rest assured that I almost never padded my expenses (or at any rate got caught doing so), but I often took Nancy with me on these trips--especially if the honorarium would pay her way--and sometimes we took the kids too.

And starting in 2013, I really hit the jackpot with a sequence of three invitations to give a Bloomsday lecture on Ulysses for the alas-now-disbanded Lannan Foundation of Santa Fe (see Chapter 3), which not only treated Nancy and me each time to travel and three days' stay at the luxurious Hotel Santa Fe Hacienda but also laid on an honorarium close to five figures.

But let me start with the weirdest experience I ever had: getting stopped dead just fifteen minutes into a keynote lecture in Tel Aviv.

Having been asked to give the lecture at a conference to be held at University of Tel Aviv in March of 1997, I decided to take Nancy along, especially since neither of us had ever been to the Middle East, and to combine Israel with a trip to Egypt. Because Egypt would then admit no one whose passport had been stamped in Israel, our would-be round trip from the U.S., to Israel for the conference had to be first of all a passport-free pass through the Ben Gurion Airport en route to Cairo. We spent a lovely week cruising up the Nile from Luxor and the Valley of Kings to the Aswan Dam and then back down to Karnak and Dendara, with a flight over the dam to see the Great Temple of Abu Simbel, whose entrance is flanked by four colossal statues of the seated Pharoah Ramses II:

To save Abu Simbel from flooding when the Aswan Dam was built, a multinational team of archeologists, engineers, and heavy equipment operators spent four years (1964-1968) moving the temple upriver around the dam to its present location. Amazingly enough, they managed to ensure that on the birthday of Ramses II in October as well as on the anniversary of his ascension to the throne in February, the first rays of the rising sun still pay homage to the four statues of him in the innermost temple--as they first did around 1265 B.C.E., when the temple was completed after twenty years of work.

But I digress from my story about my keynote lecture in Tel Aviv.

Beforehand we spent our Jerusalem days at the American Colony Hotel, which turned out to offer not just a truly delectable breakfast buffet but also, we were told, a hotel bar where foreign journalists from all over the world could safely trade their stories and secrets without being eavesdropped by anyone from Mossad. Having overheard nothing confidential or consequential in that cozy bar myself, I simply cherish the memory of its clandestine vibes.

And of course we saw the major sites of Jerusalem: the Wailing Wall, Temple Mount aka (for Arabs) the Noble Sanctuary, the Via Dolorosa, and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, with its oddly squeezed Crusader-era façade, where many people believe that Christ was buried before he rose from the dead:

Sorry for another digression here. Now on to the conference and my aborted keynote!

Leaving Nancy and Virginia behind to see Bethlehem and Masada before following me to Tel Aviv, I taxied to my hotel there, learned just why its elevators stop at every other floor on sabbath days (any observant Jew can explain this if you don't know already) and got to the conference during a coffee break about an hour before I was scheduled to speak. After various greetings and handshakes and small talk we all adjourned to the auditorium in which I was introduced as the keynote speaker with due homage paid to my academic credentials.

My topic was "The Rhetoric of Art Criticism," but before plunging into its rather academic argument, I had decided to loosen up the audience with my favorite story about slide lecturing, which had not yet given way to the now ubiquitous ease of Power Point and digital projection.

Some years before my trip to Tel Aviv, I had hosted at Dartmouth a visiting Phi Beta Scholar (and longtime friend) named Jean Hagstrum, Professor of English at Northwestern University. As the author of a landmark book called The Sister Arts (1958), Jean was one of the founding fathers (yes, Jean was male) of interart study in America during the years that followed, and his proteges actually included the now renowned W.J.T. Mitchell. So it was a great honor to host him and help arrange his slide lecture, which was scheduled for a basement theater in Dartmouth's Hopkins Center one afternoon at 4:00 PM.

So at 3:00 PM I left Jean at the theater, where two slide projectionists plus a third to supervise them were already in place awaiting his instructions. There was just one problem: though Jean had brought all his slides in one carousel, the projectionists had only two straight slide trays, which meant that Jean's slides had to be individually transferred from the carousel to the trays--and in an order that somehow preserved the carousel order even while switching from one tray to the other.

You can probably begin to guess how well this process worked. When I returned to the theater at 3:30, I found that our distinguished lecturer--then in his late 70s-- was literally on his knees trying to place his slides exactly where he wanted them in the two trays. But he had so much difficulty that we began to lose our audience as the clock ticked up to 4:15, so I urged Jean to make a start at once--hoping for the best.

Unfortunately, Jean had not yet got all the slides where he needed them to be, which was doubly unfortunate because he had not delivered this lecture for some time. As the slides began to pop up in an order bearing no connection whatsoever to the words of his lecture, it was equally obvious that he had forgotten what some of them were and began asking me if I recognized them. Then at one point he walked to the back of the theater stage to make a point about a slide that had just shown up on the white screen there--and then suddenly disappeared into a trench that lay open just under the screen. By the time I had rushed up on the stage to rescue him, however, he had already managed to climb out of the trench, and after dusting off his suit, he somehow managed to finish his lecture with astonishing aplomb.

So after telling this story to my audience at Tel Aviv, I told them that every time I launched myself into a slide lecture, I said just one silent prayer: Dear God, please keep me out of that trench! And since that got a hearty laugh, I felt heartily licensed to launch the lecture I had carefully prepared--and for which I had all my slides in a carousel that I had simply handed to the projectionist.

There was just one problem: having been told that mine was to be the keynote address at this conference, I assumed that I would be given at least an hour to deliver it. In fact I had been slated for half an hour, which meant that after telling my story in leisurely fashion I had about 15 minutes left. So 10 minutes into a lecture that should have lasted at least 60, I was handed a card telling me to wind it up in five minutes! Which meant cutting at once to a bald summary of it on my very last page.

I have since then many times compared what I did with what I might have done. I might have simply thrown the card away and plunged right on all the way through the lecture I had prepared. I might have read the card aloud and asked the audience to vote on how I should proceed. (I think that would have won the day.) But I didn't do either of those things. Instead I meekly cut to my final page, left the stage, and sat down seething in sullen silence. My only consolation was the thought of what I might say if I were ever again invited back to Tel Aviv with assurances that I would be given all the time I needed to give a lecture. Accepting almost in spite of myself, I would say, "I'm just a goy who can't say no!"

But I was never invited back.

About ten years later, in early November of 2008, I was asked to give the opening lecture at an International Colloquium titled "Ut Pictura Poesis: Words and Images in Literature and Art" at the University of Rosario, Argentina. This time I was hosted by an altogether lovely, learned, and erudite scholar named Ana Lia Gabrieloni, who did everything possible to ensure that I had plenty of time to deliver my lecture in full. She even translated it in full so that the Spanish version could be shown on a teleprompter for the benefit of non-English speakers in the audience. And though the teleprompter jammed--alas!--just as it started to roll, the lecture was well received by those who could understand my English and the Q & A afterwards was conducted with the aid of translation.

In addition, our trip to Rosario (Nancy came along) offered us a crash course in the stubbornly Peronist politics of Argentina. Long after Evita had died in 1952 after telling all Argentina not to cry for her, long after the Mussolini-adoring, Nazi-coddling Juan Peron himself had ended his third term by dying in 1974, long after he had been buried in Buenos Aires' La Chacarita Cemetery (where on 10 June 1987 his tomb was desecrated and his hands cut off with a chainsaw by unknown burglars), Peronisme remained very much alive. Essentially, its heirs have bought the blind allegiance of the descamisados--the shirtless ones--by starving those I privately call the descojonesados--the castrated progressives of the middle class, above all its hungry academics. While the University of Rosario is an island of liberalism whose faculty were vastly relieved to learn that I was not a Bush supporter (as they had feared), and were each and all a pleasure to meet, the university itself was so little supported that many of its faculty were working without pay, just to list their jobs on their resumes, and had to support themselves by moonlighting elsewhere on weekends with tutoring jobs.

But a bigger threat to Nancy and me were the pickpockets of Buenos Aires, which is where even Fagin--the master pocket-picker of Dickens's Oliver Twist--would have found himself hopelessly outclassed.

On the morning we left Rosario for a few days' stay in Buenos Aires, Ana Lia warned me sternly against its pickpockets--and sternlier still when she rightly thought I was not sufficiently attentive. But after a couple of days of moving around the city--via taxi as well as foot--without incident, we or rather I wholly ignored her warnings during a visit to the Bellas Artes museum on the one day a week that it happened to be free--no admission fee. My rather fat wallet, in fact, was right there for the plucking in the right rear pocket of my trousers, with nothing above it but a short-sleeved shirt on this sunny day of temps in the mid-70s.

After getting out of a taxi at the curb opposite the museum, we walked back to a crosswalk, joined a large crowd of people waiting for the walk light, and of course gave no thought to anyone who might have come up behind us with ample time to notice the enticing bulge in my right rear pocket. But after we crossed the boulevard, turned right, and walked a few steps toward the museum, we felt a hail of drops that might have come--so help me-- from a covey of pterodactyls. Rather than realizing at once that no single bird could have dropped such a load on us, we turned around to see a man and a woman walking close behind us and providentially armed with what appeared to be small water bottles and little white wipes!

My instant thought was not that alarm bells were now ringing loud enough for even stone deaf ears to hear but rather, "Here is sudden relief for our spotted clothes!"

So while Nancy wisely clung to her pocketbook as the couple gently but firmly guided us off the sidewalk and behind a billboard (so we could all have some privacy!) I gratefully stood presenting my whole backside to the kindly stranger so that he could vigorously rub the nasty spots off my shirt and trousers.

Of course I knew that this put my wallet within easy reach of his hands, so I made my right buttock work overtime to see if anything was disturbing it. But since he was rubbing my back and buttocks vigorously all this time, it was impossible to know just what his non-rubbing hand might be doing, so I simply decided--with a little nod to Tennessee Williams' Blanche DuBois--to trust the kindness of a stranger.

And just after they finished and peeled off, I was relieved to find the wallet still there in my pocket--even though all that hard rubbing had done nothing for the spots, which after all could easily be removed by dry cleaning, as in fact they were two days later.

What I didn't realize but what the couple obviously knew is that since the museum charged no admission that day and sold neither gifts nor souvenirs from its shop nor food from its cafeteria, I would have no need to even open my wallet for at least an hour. So it was at least a good two hours later that I realized what was missing. When I opened the wallet to pay for the lunch we had just eaten at a restaurant near the museum, I discovered that both my credit card and my ATM card were missing.

Fortunately, Nancy still had both of her cards, so she paid for our lunch before we rushed home to phone Citibank Visa and our local bank about the ATM card, and we were lucky enough to get both offices before they closed. It turns out that during the nice long stretch of time when our kindly spot-removers knew I would not be using my credit cards, they had managed to charge about $3000 to the credit card and extract another $3000 from the ATM debit card--which must have taken some doing because using my ATM--like using all others that I know of--supposedly requires separate knowledge of a 4-digit code known only to me and my bank.

But as I say, this couple not only required one or two gringo lambs like us, just waiting to be shorn of their digitized dollars (they never touched our dollar bills or pesetas) but also practiced the kind of prestidigitation that might have made the late Ricky Jay--world-renowned maestro of card tricks--weep with envy. For all the while my man was hard-rubbing my backside with one hand, the other was extracting my wallet, slipping out its two bank cards, and then putting it back in my pocket--all with just one hand! Unless his lady friend lent him one of her hands while rubbing Nancy's backside with the other. We'll never know.

In any case, it was a lesson learned on the cheap. Together, Citibank and our local bank covered all of the $6000 charges--though without even trying to explain how the thieves managed to make those would-be secure cards--especially the would-be passcode-secured debit card--pay out so much. So I tried to console myself by rationalizing that we had been honored, as it were, by two of the deftest pickpockets in the world. But I can't altogether shake the feeling that the leading role in this whole episode was played by my own willful stupidity. Instead of going about with a fat wallet stuffed so obviously and temptingly in my right rear pocket for all to see, I could have left the whole wallet safely locked up in our rented Palermo apartment, wrapped a credit card and perhaps 50 pesetas inside a handkerchief, and then tucked the little thin white packet into my shirt pocket or one of my front pants pockets--leaving both of my rear pockets empty. Or put them all into a money belt. Summing up: it would have been so easy to foil even the greatest pickpockets of the world--if I hadn't recklessly jettisoned the stern warnings of Ana Lia on the last morning I saw her.

The one other trip that comes floating to mind at this point involves neither pickpockets nor an aborted lecture but rather a crash course in the sudden emergence of a Warsaw pact nation from behind the iron curtain in December of 1989--just after Gorbachev decided to withdraw the Soviet Army from Eastern Europe and let the Berlin wall start coming down.

Having been invited to participate in a small conference on art and literature (what else?) at the Technical University of West Berlin, I immediately accepted--in part for the great pleasure and excitement of just seeing that ugly wall get breached. I even brought a small hammer and chisel in hopes of hacking my own souvenir chunk out of it, though I got only crumbs for my trouble.

But the main attraction of this trip was an invitation to join my Dartmouth College colleague and good friend Stefan Scher in Budapest, where he would be staying with his widowed mother in the very same apartment where he had spent the first 18 years of his life.

So right after the conference in West Berlin, Nancy and I took a bus to the Schönefeld Airport in East Berlin for the flight to Budapest because there was no other way to get there. En route we were stopped and grimly passport-checked by stalwart agents of the Stasi----the secret police of the German Democratic Republic (in German the DDR), who had done everything possible to undermine both democracy and republicanism in what was then East Germany. Knowing just a bit of German, I amused myself on the bus by mentally composing a new version of O Tannenbaum that of course I did not dare to sing or even whisper aloud:

O DDR, Ich liebe dich,

[O DDR I love you]

O DDR, Ich liebe dich,

Und deine schöne Polizei,

[And your beautiful police,]

Und deine schöne Polizei,

O DDR, Ich liebe dich,

Und deine schöne Polizei!

After a long delayed takeoff (big surprise there, right?), our plane reached Budapest so late that even though we had fully paid for a handsome corner room at the brand new Hilton Budapest on the cliff overlooking the Danube, the hotel had given away our room and booked us for one night into the Sheraton across the river-- in the lower half of the divided city known as simply Pest. I was very cross, but the manager who handled our case lubricated it with so much charm and so many lavish liqueurs that we didn't stay mad for long, and by early afternoon of the next day we had settled into our suitably luxurious room on the cliff.

The lobby of the Hilton was mobbed by deal makers eager to play their parts in the re-capitalization of Hungary at this truly revolutionary moment. As Steve later explained to us, Hungary had remained throughout the Soviet era the freest and most prosperous of the Warsaw Pact nations, since it could not only feed itself with a thriving agriculture industry but could also manufacture and sell its own lamps through Tungsram Operations--and thus do business with the West on at least a modest scale. So when Gorbachev blew the whistle, Hungary was more than ready to run.

During the mainly Hungarian-language Sunday Mass at St. Stephen's Basilica, just a short walk along the cliff edge from our hotel, I was delighted to hear the Apostle's Creed--Credo in unum deum-- sung in Latin, which I happily joined in singing. For the very first time in my life I experienced the universality of a language I had long learned how to sing as well as speak. It was the voice of an old friend breaking through a language I knew not at all.

Well, actually, Steve had taught me a few of its words and phrases such as Jó nap! (Hello!), Hogy vagy (How are you?) and Nagyon jó egészségedre! (To your very good health!), but you had to be very careful with those toasting words because if slightly mispronounced at the end they could mean "To your whole ass."

In any case, having settled ourselves at the Hilton and heard one of the first masses celebrated in Budapest in something like 70 years, we were more than ready to reconnect with Steve and meet his mother in the very same apartment--over in Pest--where he had spent his boyhood and early adolescence.

Greeting us at the door of her apartment, Little Lady Scher--in Hungarian Kissaszony Scher-- turned out to be a kindly witch. Short, plump, dressed all in black and amply crowned with hair dyed a matching black, she greeted us warmly, and the smile on her pale but also slightly rouge-cheeked face widened as soon as she heard me say, "Jó nap! (Hello!), Hogy vagy!" (How are you?). For she then assumed that I spoke fluent Hungarian, which of course I did not. In any case Nancy charmed her at once without speaking a single word of it, and her verdict on Nancy was simply "nagyon szép!" (very nice!).

Sitting down to coffee and petits fours (bite-sized macaroons, éclairs, madeleines, etc.) with Steve and his mother and his very lively aunt was like stepping through a time machine back into the mid-20th century, or even pre-WWII Mitteleuropa. Curtained in old lace, the apartment was not only high-ceilinged but also quite large enough for at least a family of four even though the Soviets had long since cut it down to half of its original size. Sitting in the well-worn but nonetheless comfortable furniture of the white-washed living room, we each drank from a cup tucked into a zarf, if you please: a vintage Russian silver tea cup holder made to hold a cup with no handle of its own.

And while we all chatted happily in our respective tongues, Stefan just as happily translated everything we said.

At this point I realize that I must tell you more about Steve himself:

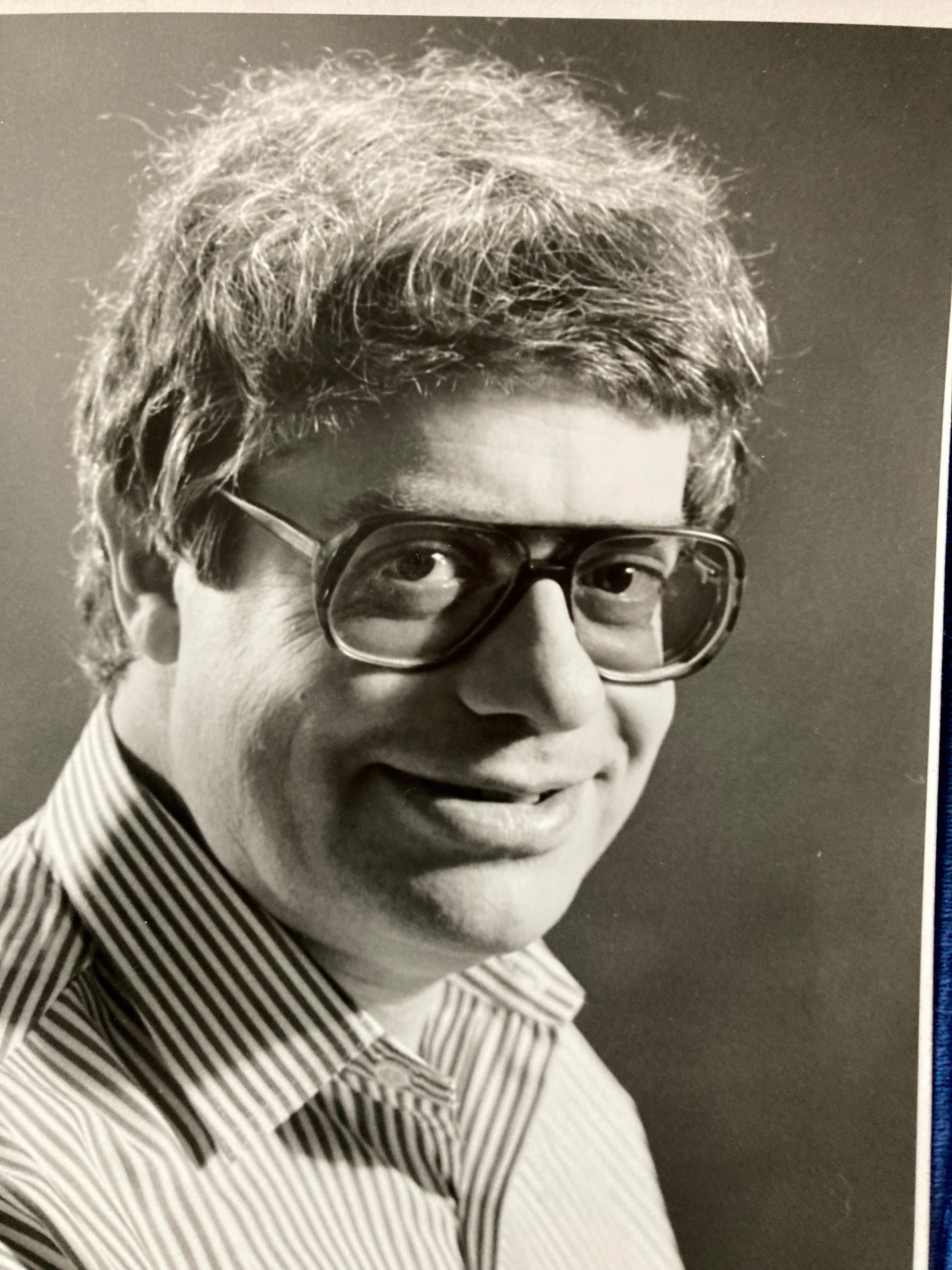

Steven Scher, Circa 1985

Steve was short, well-bellied, and beer-barrel chested, and his favorite coat--actually a rough brown leather vest--made him look something like an American cowboy. Set in a round face crowned by curly reddish-brown hair, his eyes perpetually twinkled and his mouth perpetually twitched on the edge of a grin at the latest in whatever stream of absurdities might be offered by the world around him--especially the academy.

Born and raised in Budapest, he was the only child of a man who before the war had run a small factory making soda but was afterwards allowed to work only as a night watchman there. During as well as after the war, however, Steve's secularized Jewish parents did everything they could to shield him from the horrors of the holocaust and other privations.

Well-schooled in various subjects, he was also well-nurtured in classical music, which he often played with school friends at home musicales supplemented by opera, which he sometimes heard in a sumptuously perfect setting: the nearby Hungarian State Opera House--an 1884 gem designed by the renowned Hungarian architect Miklós Ybl, where we ourselves would hear Mozart's Marriage of Figaro sung on the following Monday night.

Steve grew up in the shadow of Soviet rule, but it never darkened his irrepressible spirit. Under a secret agreement signed by Churchill and Stalin in October 1944 at the Fourth Moscow conference (aka Tolstoy Conference) dividing Eastern Europe into British and Soviet spheres of influence, the Soviet Union grabbed an 80 percent share of influence in Hungary--with the right to keep both its troops and political advisers there (Wikipedia). Though recorded nowhere else, I can assure you that about 19% of the remaining sphere of influence was secretly granted to Steve.

By the sheer force of his energy, exuberance, and the joie de vive of his wildly windmilling arms whenever he talked, Steve soon won the admiration of his classmates, who chose him as their leader in the Hungarian Young Communist League (which they all had to join) precisely because they knew he would subject them to a minimum of apparatchik-dermo (my coinage for "bureauceatic crap") and a maximum of tolerance for their own high jinks.

The spirit in which Steve and his schoolmates served the Communist regime in Hungary in the early fifties is best exemplified by the story of what they did in March of 1953, when news of Stalin's death reached the school with an impact so memorable that I have since made a poem from Steve's account of it:

MOURNING STALIN

For Stefan Scher, in memoriam

One afternoon in early March of 1953

when news of Stalin's death reached Budapest,

it stormed the city.

At Stefan's school,

where every classroom door gaped open

so nothing said or done by anyone

could not be overheard and overseen,

every boy was told to stand beside his desk

for five full minutes, silently, in homage to

the Great Leader,

the Gardener of Human Happiness,

the Dear Father,

the Man of Steel.

Like all the others, Steve got up and stood beside his desk

and held his lips locked tight.

But after a minute or two,

Something struck the pond of silence.

Like a pebble dropped behind him

he could plainly hear

a giggle.

At once it spread

growing louder and louder

rippling right through Stefan's classroom

through the always open door

into the corridor

through all the other open doors

up and down the stairwell

until at last it convulsed

the whole building,

turning its walls

into heaving bellies.

Aghast, enraged,

The apparatchiks questioned everyone,

badgered everyone,

threatened everyone

and sacked the principal.

But they never ever ever ever learned

who giggled first.

Three years later, when a brief eruption of Hungarian independence provoked a ruthless crackdown by the Red army, there was no more time for giggling. Though Steve felt bound as an only child to stay with his parents as long as he could, they finally convinced him that his life under this totalizing version of Soviet rule would not be worth living for the foreseeable future--quite possibly for the rest of his life. So in the early winter of 1957, he packed his suitcase, caught a train to within about 20 miles of the border with the now independent Austria, and walked or at any rate somehow got himself to Vienna and its University, where he managed to enroll for the spring semester and plan his next move. There Steve quickly learned German--a language never taught in any school supervised by the Nazi-hating Soviets--and also learned that because he had waited so long before tearing himself away from Budapest, all places for Hungarian refugees in British universities were already taken--and taken also at Harvard, the only American university he had heard about. Fortunately, however, someone told him of another institution in a city nearby--someplace called "Yale." So with beginner's German and scarcely any English at all, Steve gained admission to the sophomore class at Yale for the fall of 1957, got himself to New York by June of that year, landed a job delivering telegrams by bicycle around the city, and also learned enough English to be ready for classes in that language in September.

Did I mention that Steve could devour a new language as a lion devours an antelope? That he relished American idioms and slang of all kinds the way a gourmet might savor foie gras? I have never known anyone else whose love of learning languages and tasting their distinctive pleasures could match his.

After taking just three years to gain his BA at Yale, Steve earned a PhD in German literature there and taught at Columbia and then Yale before joining the Dartmouth faculty in 1974 as the Daniel Webster Professor of German and Comparative Literature. By then he had also acquired a lifelong partner named Ulrike Rainer, a brilliant young Austrian woman who came to the U.S. as an au pair in 1966, got herself into Yale after acing the courses she audited there, earned her own PhD in German literature at Harvard, and wound up teaching at Dartmouth as well as living with Steve for the rest of his life.

Shortly after Steve joined the Dartmouth faculty, I met him in a Baker Library seminar room just as he was winding up a class on Thomas Mann's Magic Mountain--and I was mightily impressed to hear two students animatedly discussing the novel in German and talking only between themselves--not for the professor. That day began my friendship with a man I came to know and love until he died of heart failure at the age of 68 on Christmas night in 2004.

By then he had not only launched a battery of special programs for Dartmouth students in Germany as well as in the U.S. but also made himself internationally known for his voluminous publications on literature and music as well as German literature. Above all, he was invariably delightful company--even when railing at something or someone he loathed. Funny, irrepressible, fiercely opinionated, utterly captivating and just as utterly unforgettable. That was Steve.

OK, back to his mother's Budapest apartment for coffee and petits four with his mother and aunt.

Steve had planned for us to meet his old friend Janos (who had stayed behind in Budapest when Steve left it), to meet us for Hungarian goulash at the best restaurant in town. But it was Steve's job to make the reservations--not an easy thing to do, since even getting the phone number for any restaurant in Budapest at this time was about as easy as cracking a nuclear code. So what ensued was a trio worthy of Mozart as Steve and his mother and aunt gathered around the little telephone table in the dining room and first of all debated in ever-rising decibels and undulating glissandi the merits of the best two (or was it three?) restaurants in Budapest and only then tackled the arduous job of tracking down its phone number, which called for still more glissandi along with riffs and the mellowest of melisma. We almost stopped them on the grounds that they were spoiling our appetites for Mozart's forthcoming Marriage at the opera house.

Somehow, miraculously, Steve booked us a table at a what proved to be a bright and jovially crowded restaurant where we had what I'm sure was the best goulash to be then had in Budapest: trois étoiles, M. Michelin, et rien à redire !

But the best thing about that meal was meeting Janos, Steve's boyhood friend, who had stayed behind when Steve left Budapest all those years ago but remained his friend and somehow retained his own good humor in spite of all the setbacks and frustrations he had endured--going all the way back to his childhood. (Half-Jewish on his mother's side, he had Czech citizenship thanks to his father, so as a kid he could visit the Ghetto and bring some food to his Jewish grandfather, who was confined there.)

Janos told us a marvelous story of clocks and watches in Budapest at the time when the Soviets "liberated" Hungary from the Germans in late 1944.

When the Red Army rolled into a Budapest from which it had finally routed the hated Nazis, its soldiers were ecstatically welcomed by citizens holding out at full length both of their often sleeveless arms , which the Russians "shook" by starting just below the armpits and then stripping all the way down to the fingertips--thus relieving their welcomers of every bracelet, ring, and of course wristwatch they might have been wearing.

The last was the Russians' chief target. According to Janos, a gang of Russian soldiers barged one fine day into the shop of a Budapest clockmaker with a Grandfather's clock at least six feet tall--and demanded that he break it up into wristwatches.

Anyway, this little story about watch-swiping by the Russian army of "liberation" is the background to a certainly apocryphal but nonetheless delectable story about what happened in early February of 1945, just after Churchill, Roosevelt, and Hitler met at Yalta (in the now embattled Crimea) to carve up their "spheres of influence" in Europe after the end of WWII.

The British delegates to the Yalta conference, it seems, gave to Churchill a large silver watch inscribed: "From the People of Britain to the Savior of Britain."

Not to be outdone, the American delegates to the conference gave to Roosevelt a still larger gold watch inscribed:

"From the People of the World to the Savior of the World."

And at last, not to be outdone by any of these capitalist dogs, the Soviet delegates to the conference gave to Josef Stalin a still larger platinum watch inscribed: "To Prince Ezterhazy from the Vienna Jockey Club."

Let me end this wild and wandering story of three trips to Argentina, Israel, and Hungary with a story about the most unforgettable party that Nancy and I ever attended in our lives--in Tokyo.

By what seems to be universal consent, the greatest party of the twentieth century was the Black-and-White Masquerade Ball held on November 28, 1966 at the Plaza Hotel in New York City and hosted by Truman Capote in honor of Katharine Graham, then publisher of the Washington Post. Endlessly described, commemorated in Wikipedia, and even featured in novels such as Don DeLillo's Wonderland, the Black-and-White Ball has taken its place in the cultural history of 1960s--at the very least.

But if there is such a thing as a list of nominations for the greatest party of the twenty-first century, here is mine.

On April 22, 2006 (which just happened to be my 67th birthday), Nancy and I attended a party in Tokyo given for Wim Wenders, the German film director best known for movies such as Paris, Texas and Wings of Desire. In town to launch an exhibition of his photographs of Japan, a country he very much likes (his films include Tokyo-Ga, a documentary about Japanese film director Yasujirō Ozu), he was accompanied by his sixth wife Donata, who was launching an exhibition of her own photographs---in black and white, so as not to compete with Wim's color shots--and both sets of photographs would later become a single exhibition, Journey to Onomichi. There were no photographs exhibited at the party, and we left Tokyo before we could see them, but the party offered more than enough to see--and hear.

It was held on the top floor of a new 47-story building in Tokyo's glitzy Ginza District, which might also be called Manhattan on steroids. Flanked by floor to ceiling windows on two sides, the restaurant--a smart new Italian eatery whose name has escaped me (it might have been the Piacere in the Marunouchi Trust Tower)--offered breathtaking views to the north and east. To the east, just beyond the Tsukiji fish market (the greatest fish market in the world, which we had risen bleary eyed at 4:00 A.M. to see in its usual pre-dawn Saturday action but which turned out to be closed because of a holiday!), stretched a forest of glittering skyscrapers just about as far as the eye could see--all of them built, we were told, within the past ten years. To the north the view was much the same: just dazzling.

But there was plenty to see indoors too. Our host was a portly man of late middle age wearing a baseball cap and dressed in shirtsleeves. I took him at first for an overage busboy or some harmless oddball who had wandered in off the street (though of course he would have had to wander up 47 flights too). But I recognized his name as soon as I heard it: Joni Waka, a name that he says is Manchurian but that he pronounces "Johnny Walker," like the whiskey, just to be sure everyone remembers him, as indeed everyone does.

Born in San Francisco, where he spent the first ten years of his life, Johnny sounds American, but with blood flavored by his Manchurian ancestry he's become a citizen of the world. His checkered career as a stock-broker and wheeler-dealer of sorts in Russia and various other exotic places has finally led him to Tokyo, where he seems to survive--and indeed thrive--on a rare combination of master networking and plain old chutzpah. A sample of his style: when I told him--in response to a question about my work--that I had recently finished a book on language and art with a good deal to say about Turner and Constable, he promptly introduced me around as a noted London art critic.

We got invited to this party because the scads of notables that Johnny knows or at least effectively cultivates in Tokyo include the director of an organization that had awarded a fellowship to David, who was then married to our daughter Virginia. The fellowship included two months' residence in a comfortable two bedroom apartment (huge by Tokyo standards) in northeast Tokyo, which is what led us to the city in the first place: Virginia and David could put us up.

So, back to the party. Something like 150 people in a brand-new classy Italian sky-high restaurant with wine flowing like Niagara at a cost of what would have to be something like a hundred bucks a person, conservatively. So part of the talk among us focused, sotto voce, on just how Johnny Walker was doing it--since in spite of his fabled past and legendary exploits and would-be grand connections, he has precious little visible means of support.

Shortly after we found our way to a table right by the window looking north (we had seated ourselves after about an hour of drinking and milling about), we were joined by a fiftyish American woman who looked like an altogether decorous veteran of the Junior League and proved, in fact, to be a cultural attaché at the American Embassy. So after exchanging pleasantries we asked her if the Embassy was footing the bill for this shindig. Might as well have asked her if the Embassy was hosting a bash for Osama bin Laden. Absolutely not! And she had no idea who was paying for it. But of course she had not declined the invitation. Who would? She was pleasant but a bit guarded, the perfect embodiment of a certain kind of American upper middle class normality--against which could be measured the captivating idiosyncrasies of everyone else, not necessarily counting ourselves.

We never solved the mystery of who paid for the party. Some speculated that the restaurant might have comped the whole thing to gain publicity, to launch itself--as it were--on a tide of glitterati, but the absence of any visible means of support simply enhanced the atmosphere of glorious unreality. We were a floating island of festivity--which was just right since the Japanese speak of high class prostitution, I believe, as Fuyū sekai-- a floating world, a world unanchored and unmoored.

OK, cast of characters. Wim was tall, lean, rugged, shaggily grey and somewhat laconic--at least in my hearing. No "public" speeches of any kind to the crowd, just a few polite words as I shook his hand on the way out. But Donata, wife number 6, was another matter. Tall, slim, blond, with concave cheeks and angular features, not conventionally pretty, but very striking. Dressed in something that only Nancy could properly describe, she wore--as best as I can remember--a tight black bodice with a flared skirt and boldly figured layers worn like feathers: something like a Swiss milkmaid reconfigured by Valentino.

Anyway, she sat next to Wim at a table in the middle of the room and shortly made herself the cynosure of all eyes, including ours of course. When David noticed Nancy's interest in her, he walked over to her table and whispered something in her ear. Shortly afterwards, Donata swished over to our table, looked straight at Nancy, and said quite distinctly, "I just wanted to meet the most beautiful woman in the room." So you can understand why Nancy had a very good time that evening.

The rest of the cast included an actress named Shinobu Terashima, who was then something between a movie star and a super-fashionable girl about town. She descends from eleven generations of Kabuki actors, including her father, Onoe Kikugoro ("a living national treasure") and her brother. Since no woman can do Kabuki, her brother plays love scenes with his father--all in no doubt proper Shakespeare-era fashion. She was quite charming, and told me the name of the movie that she had just finished: It's Only Talk. I've since learned that she previously starred in Vibrator (2003, and no cracks about the title, please!), and Riding Alone for Thousands of Miles (2005)--both now available on DVD. (Since the party, she has won awards for her acting in movies such as Caterpillar and Oh Lucy!)

There was also an Australian poet named Destiny trailing her partner/manager--a younger woman coincidentally named Virginia--in town to promote her latest book and give a reading. Round, irrepressibly effusive, and crowned with an immense bush of hair, she took an instant shine to Nancy for reasons none of us understood and smothered her in hugs at every possible opportunity--to the visible annoyance of her partner. If we ever get to Sydney or Melbourne (no immediate plans), I visualize her rushing up to Nancy and enfolding her in a boa-constrictor embrace. That would be our Destiny.

And of course there were designers, photographers, fashion people, import-export people, people from embassies, and the occasional bank officer just in from Kyoto or Osaka--perhaps because he once loaned money to Johnny and was still touchingly hopeful that he might see it again, or at least some fraction of it.

At the table next to ours sat a rather voluptuous woman dressed in a skin-tight black pantsuit and sporting a jeweled ring (diamond, maybe?) on the very tip of her pinkie. She was from Hong Kong, I believe, and now works in Tokyo designing and exporting these rings and other bibelots. Sotto voce, David ventured to say that she might also be engaged in a somewhat older profession. On this floating island, who knew? Who cared?

But the pièce de resistance--if there was one--was a slightly scruffy-looking guy who looked to be around 45 standing a few feet away from our table and wearing a silk skull cap. When he turned his back to us, we noticed that his hair was bound into great thick ropelike braids that fell--I'm not making this up--all the way to the floor. Of course Virginia had to learn about these, so she walked up and asked him how long it took to grow them. "Twenty years," he said. "It's the greatest achievement of my life." And that, we all agreed, was one of the greatest parties of our lives.

Back in Virginia's Tokyo apartment, I topped off the evening with one more glass of bubbly and a narcissistic toast to myself that I have been giving for years on April 22, a birthday I share with Henry Fielding (the 18th century English novelist), Vladimir Lenin (godfather of Soviet Communism), and Immanuel Kant (the eighteenth-century German philosopher):

Fielding, Lenin, Kant, and I

Did this day our first light see.

Drink then, friends, with glasses high

To Fielding, Lenin, Kant, and me!