CHAPTER 3. TIMELINES 1965 TO 2024

In 1814, when Walter Scott published what is commonly considered the first historical novel in the Western tradition, he called it Waverley; or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since because it commemorated what had happened roughly sixty years earlier: the doomed Jacobite rebellion of 1745, when Charles Edward Stuart--Bonnie Prince Charlie--led an army of Scottish Highlanders in quest of the British throne before they were crushed at Culloden in April of 1746.

It is now almost sixty years since I came to Dartmouth in the fall of 1965, when the United States was waging a doomed war to liberate South Vietnam from a Viet Cong based in the north. President Lyndon Johnson and his team of wise old men stubbornly believed that the North was a puppet of Communist China and the South just a domino (ah, that deadly metaphor!) whose "fall" to Communism would end up topplng just about every other country in the "free world" except perhaps our own. As everyone now knows, the U.S. gave up fighting the North Vietnamese in January of 1973, and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam remains to this day both Communist and independent of China. As I look back at everything that has happened during the past sixty years, I first envision them as an old-fashioned newsreel of headlined clips interspersed with family moments and yours truly popping up now and then like a Jack-in-the-Box, or like the nobody in Woody Allen's film Zelig, thrusting himself just inside the frame of major events. So rather than treading the tedious path of conventional chronology, here for now is a more or less random timeline of my life and times--including shamelessly self-indulgent notes on my occasional successes as well as mea culpas for occasional follies.

Fall 1965. We move into our first Hanover apartment--two bedrooms plus kitchen, bath, and small living room in the renovated top floor of a barn standing next to the Petco station on Route 10, the road running south from Hanover to West Lebanon. I think we paid $125 a month.

The main advantage of this arrangement is that it led to our lifelong friendship with the wife of the owner, a salesman she left a few years after we first knew them. During our year of sharing the house with these two, who lived downstairs, Pam taught English at the Mascoma Valley Regional High School for sixty dollars a week, a salary that had to cover--among other things--the cost of commuting a dozen miles each way (and in the winter through snow and over ice) to the town of Enfield. But in spite of her husband's disdain for the pittance she earned, she poured her young heart and soul into the teaching of poetry and creative writing, and her students, she now tells me, sent a copy of their literary magazine, Another Voice, to J. D. Salinger, who replied in a letter to Pam,"I think it's an extraordinary collection, and I don't say that lightly....I do ask you to believe that I'm not used to reading collections as fine as this one."

Though Pam has just been offered $1500 for this letter, which is precisely 25 times her weekly salary at the time she was teaching those kids, she has turned down the offer. How could anything in the world be more precious than those few words from one of the most famously--or infamously--reclusive writers who ever lived?

During this time she also started writing fiction herself. And through all the almost sixty years since then, she's never stopped honing her craft. Her fifth book of stories, Fabrications, was published by Johns Hopkins in 2020. And if you like short stories, you may have guessed by now that I've been talking about an award-winning writer named Pamela Painter.

March 31, 1968: Mired in the quagmire of Vietnam and facing massive resistance to the draft from young men shouting, "Hey, hey, ho, ho! LBJ has gotta go," Lyndon Johnson announces that he will not run for a second term as president.

January 1, 1969 Cornell University Press publishes my first book, Wordsworth's Theory of Poetry: The Transforming Imagination, a rewrite of my Princeton dissertation. In the following year it gets a rave review in the Journal of English and Germanic Philology from the late Jack Stillinger, who writes that it "takes its place beside Geoffrey Hartman's Wordsworth's Poetry . . . as one of the two most significant books on Wordsworth of the 1960's." Bless you, Jack, but even I must admit to being overpraised here. Hartman's book remains a classic; mine was an interim report. But it ended up selling 2200 copies, which is not bad for an academic monograph.

8 August 1969: Nancy delivers our first child, daughter Virginia , who will grow up to become much better known than yours truly for the scintillating panache of her prose.

May 1970. Promoted to Associate Professor, I become a tenured moderate. Left of center but never a tenured radical.

May 9, 1971 Nancy delivers our son Andrew, who will become a fitness trainer, much-published writer on fitness, and avocational actor whose one man performance of Joyce's short story "The Dead" (https://www.thedeadsoloshow.com/) captivated all who saw and heard it in early July of 2023 during a Heffernan clan reunion at the Lakeside Hotel in Ballina, Ireland.

1 September 1972. After arduously canvassing its all-male alumni and searching its once irredeemably masculine soul, Dartmouth admits 177 women to its first-year class and 74 as transfers to its upper classes.

Though these brave canaries in the Big Green mine are at first derided as "Co-hogs" by many of their male classmates, and though I know of at least one of those males who decided against taking a history course as soon as he learned it would be taught by a woman, Dartmouth soon grants "equal access" to both men and women and sets out to put a substantial number of women on the faculty. As of September 2023, it has its first woman president: Sian Beilock, a cognitive scientist who was formerly president of Barnard College in New York.

JANUARY 22, 1973 By a vote of 7-2 in the case of Roe v. Wade, the U.S, Supreme Court affirms Justice Harry Blackmun's argument that the U.S. Constitution generally protects the right to have an abortion.

Though the mostly Protestant majority included Justice William Brennan, Jr., a Roman Catholic son of Irish immigrants, the ruling must have been a bitter and humiliating blow to my father, even though I never heard him mention it thereafter. Having passionately argued that even "therapeutic abortion" was "legalized murder," what could he possibly say about the legalizing of all abortion?

Let me tell you just how he fought abortion.

On February 1, 1952, 21 years before the Roe ruling, the Linacre Quarterly:: A Journal of the Catholic Medical Association published his article (co-authored with Dr, William F. Lynch) titled, ("Is Therapeutic Abortion Scientifically Justified?") It began by unquivocally (but not very scientifically) answering the question posed by its title:

The argument against therapeutic abortion from natural law can be stated very briefly. The unborn child is an innocent human being; its life is inviolable. To destroy that life deliberately is murder.

Ah! but some of our professional confreres will say: "From a strictly scientific standpoint, isn't it thoroughly justifiable to empty the uterus before viability when a continuation of the pregnancy would endanger the life of the mother?" Our answer to this question is an unqualified NO. It is never justified from a strictly scientific standpoint.

When this article appeared, I was twelve years old--old enough to be aware of its sweeping claim but not equipped to examine the evidence adduced to support it. In recent years I have increasingly wondered just how these doctors made their case, which struck me on its face as quite simply impossible to prove. Now that I have finally studied the article, I can clearly see the yawning gap between their unequivocal claim (tellingly made before presenting any evidence at all) and the cases they cite to back it up,

In the wake of the momentous Dobbs decision of 2022, it is all but forgotten now that well before Roe, any doctor could legally perform a therapeutic abortion: could abort a fetus while treating a pregnant woman for a disease such as tuberculosis, diabetes, or psychiatric disorders (to name just a few).

Against this legality, RJH and Lynch argued that in many and perhaps even the overwhelming majority of such cases, doctors could effectively treat them without resort to abortion, Rather than accepting abortion as a default response to any disease that might strike a pregnant woman, RJH and Lynch argued that such diseases can often (though not of course always) be separately treated by any doctor and / or health care team willing and able to take the time and make the effort to treat them.

In other words, they accused therapeutic abortionists of taking the easy way out. In "destroying babies," they charged, the "attending doctors bowed to expediency, followed the line of least resistance and justified the murder of the fetus by saying it was the easiest, simplest and quickest solution to a difficult problem."

To this extent their argument was perfectly sound. They clearly showed that doctors had exploited the legality of therapeutic abortion by using it far more often than necessary. Yet on the other hand, RJH and Lynch also had to admit that their would-be "solution" to the problem of runaway therapeutic abortions--"solutions" such as expert and often expensive care for tuberculous pregnancies-- was not only hard to find but unaffordable for most patients.

This was just one of the flaws in their argment--their "scientific" proof that therapeutic abortion was always and without exception "legalized murder." At times, for instance, they imagine the pregnant woman who bravely carries her baby to term as a saint of self-sacrifice in the cause of child-bearing. "Patients with serious complications, they write,

require long, expert care. Some of these good mothers endure extensive periods of discomfort and invalidism. They accept uncomplainingly, the expense of prolonged hospitalization, sacrifice of social activities, sometimes the censure of unsympathetic relatives and friends. They realize that these compared with the inestimable treasure of a new life with an immortal soul are a small price to pay. Their sacrifices were not and are not in vain for with proper care these women do not die.

But unless a pregnant woman is ready to make this gigantic sacrifice, Dad, she's collaborating in legalized murder--right?

Or consider this comment on a group of pregnant women suffering from hypertension:

"the pregnancy does not seem to have had any ill effect in 52 of the 65 patients. In 7 the effect of pregnancy was unknown as their condition before pregnancy was unknown; 6 are dead."

Sorry about that, ladies! But guess what? It turns out there's an escape hatch for cases in which abortion is the only option:

When a diagnosis of malignant disease is made in the early months of pregnancy, it may be treated either by total extirpation of the pelvic organs or by the efficient use of radium or x-ray. The indirect interruption of pregnancy in these cases is the undesired, unintentional and inevitable result of the radical attack on the malignant disease and is not a therapeutic abortion.

Voila! And that's how you prove that no "therapeutic abortion" is ever "scientifically justified," and that all therapeutic abortion is legalized murder. Sorrry, Dad, but I just can't imagine a less scientific argument for your claim.

But in fact the article was never fundamentally scientific. It was driven by Dad's lifelong commitment to life itself, above all to new life, since he lived to deliver some eight thousand babies in the course of his career. He hated abortion with every fiber of his being, and this was his best shot at making a scientific case for that hatred as well as for the inviolable sanctity of all fetal life. But in the end, the case he made was a cri de coeur--a cry of the heart-- masquerading as science.

For more on this point, see my comment on the Dobbs decision of June 24, 2022--below.

December 10, 1973. After masterminding with President Richard Nixon the bombing of Cambodia, which killed well over 100,000 civilians there, Henry Kissinger is awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for having negotiated a peace treaty with the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

August 8, 1974: As Nancy and I pack up to leave the garden-level flat in north London that we have rented since January on my sabbatical, our daughter Virginia celebrates her fifth birthday by throwing a heavy metal ashtray at the head of her 3-year-old brother Andrew. When it narrowly misses him and instead breaks the window behind him, she blames him for the damage: "He ducked!"

Across the ocean on the very same day in Washington, President Nixon inadvertently takes his cue from both kids. To duck the missile of impending impeachment, he resigns over the Watergate scandal after having blamed a slew of others for it and gravely muttering, "I am not a crook."

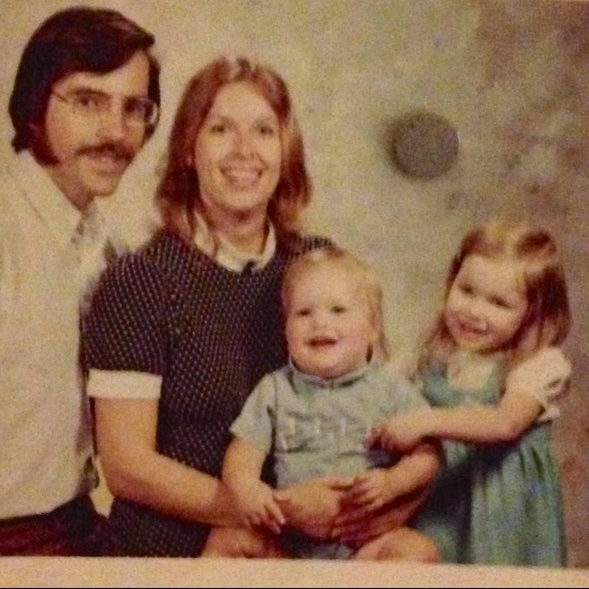

Circa September 1974: Jim, Nancy, Andrew, Virginia

May 1976. I am promoted to Full Professor of English at Dartmouth.

November 1977. W.W. Norton commissions John Lincoln and me to produce a textbook on writing for use in college courses on English composition. Five years later, Writing: A College Handbook will sell over 100,000 copies in its first year of publication, breaking all records for first-year sales of a Norton textbook. From 1982 to 2001, Writing went through five editions.

January 1979. During my first year as Chair of the English Department, I spark a firestorm by arranging to hire a female candidate who was not the wife of another tenured professor in the department after Dartmouth suddenly reversed its longtime ban on spousal hiring and instead pushed for it. Having long before wound up dead last in quest of the sophomore class presidency at Georgetown, I am freshly reminded that I am no good at campus politics. (But maybe just a little better at national politics, as you'll see further on.)

May 1981 During my last term as Chair of the English Department (my reign was short as well as troubled), Dartmouth's Committee Advisory to the President (CAP), which votes on all candidates for tenure on the Dartmouth faculty, votes down Jay Parini, who had joined us as an Assistant Professor five years before. For the full story of this fascinating case, see Chapter 8.

March 1985 Sixteen years after my first book, the University Press of New England publishes my second, The Re-Creation of Landscape. Subtitled A Study of Wordsworth, Coleridge, Constable, and Turner, it compares the nature poetry of two major Romantic poets to the work of two of England's most important landscape painters. It took me many years to write because I really didn't know how to theorize about interart relations, I'm a slow learner, and even after finishing it I had much to learn. But one reviewer, bless him, called it "a splendid achievement."

June 1986 The University Press of New England publishes the first edition of New Hampshire: Crosscurrents in Its Development, coauthored by Nancy C. Heffernan and Ann Page Stecker. Though Nancy dreaded moving with me to what she considered the frozen north in 1965, she dug so deeply into the history of her adopted state that this book has come to be required reading for many New Hampshire school kids, and was also re-issued in 1996.

February 13, 1992: Just five days before New Hampshire's presidential primary election of February 18, which was then the first in the nation, I get my Zelig moment. Since our prime spot on the primary calendar brought all the presidential candidates to us, I became for a time a political junkie. Though I couldn't afford a thousand bucks for the intimate dinner held the previous October for the Governor of Arkansas by a Democratic fund-raiser across the river in Norwich, this self-styled "new Democrat" and fellow Hoya (GU School of Foreign Service Class of 1968) soon struck me as the man to bet on. So when I learned that his wife Hillary was slated to speak for him at Dartmouth in early January of 1992, I got my Leading Edge Model D Desktop (a workhorse now long since nackered) and my clunky old ball-type printer (now also long since nackered) to clack out 300 letters (sometimes personalized with a handwritten note) addressed to everyone I knew, or barely knew, I didn't have to mail them myself; over lunch at the Hanover Inn with a member of the Governor's campaign team, I just handed him a box with all the letters stacked inside. And as a reward for my labors, I was asked to introduce both Hillary and her husband to their first Dartmouth audiences--she at noon on January 9, he on the night of February 13.

For the second event hundreds jammed themselves shoulder-to shoulder, Standing Room Only, into the Alumni Hall of Dartmouth's Hopkins Center, where they patiently waited for about three hours to see and hear this rising star in person. Soon after he finally arrived (he almost habitually ran late), I stood beside him on the stage of Alumni Hall with the mike just in front of me, the crowd massed below us, and a long row of TV cameras ranged like cannons along the back walI. I had prepared an introduction of two double-spaced pages that was cleared with the campaign and would have taken about four minutes to deliver. But as I stood beside this tall, vibrant, dynamic candidate just bursting to speak, I felt as if I were standing next to a Titan rocket with the countdown already in progress. So I cut my introduction to its final 45 seconds:

Twenty-six years ago, my wife Nancy and I moved up here from Virginia. During that time, we've seen six presidential primaries. Every four years, a fresh herd of candidates thundering across the state, snorting, stampeding, kicking up dust, and then--in almost every case--lumbering off into the Western sunset of political oblivion. I've seen many candidates, and I've even worked for some of them. But I've never seen a candidate like the man you are about to hear [THE CROWD ROARS]. For all these reasons, it gives me great pleasure to introduce to you the Governor of Arkansas and--with our help the next President of the United States--BILL CLINTON! [AN EVEN BIGGER ROAR]

For Clinton, this was a make or break night. He was running against New Hampshire Senator Paul Tsongas, himself a "new Democrat" who had already broached a new economic alternative to the social welfare policies of the now very old New Deal. Also, besides running against this well-known, well-liked home-turf senator, Clinton had just been slugged by allegations of Vietnam-era draft-dodging and tomcatting with women such as Jennifer Flowers. Driven to prove himself before this crowd, Clinton spoke for about 40 minutes without a single note but with captivating conviction and wit, took shouted questions for about 20 more, and then plunged right into the crowd for a lucky huddle of people who got to quiz him for at least another 20.

In the "holding room" afterwards he met Dartmouth's President James Freedman, who shared my admiration for Clinton as well as for James Joyce, and whom I had already come to know personally. I also shook Clinton's hand, and as you can see from this photographs taken by a former student named Stuart Bratesman, I introduced him to Nancy:

The author between Nancy and Bill Clinton, now wearing a Dartmouth sweatshirt given to him after his speech by Dartmouth College Democrats.

In 1992, after 26 years with me in New Hampshire, Nancy's Virginia accent was detectable only to those who listened carefully.

Yet even though she couldn't have said more than half a dozen words to this man who must have been thoroughly exhausted by a long long day of speechmaking and handshaking, he said to her, "That's an interesting accent. Where are you from?" He also took enough time to write on the first page of my introduction much more than his own name

"Jim--Thanks for a fine introduction and your support--Bill Clinton."

Though Clinton lost the New Hampshire primary to Paul Tsongas, he ran close enough behind him to say that New Hampshire had made him the "comeback kid," and after Tsongas's campaign fizzled out, Clinton's soon came roaring back. He also went the extra mile in thanking me for all my support, including the placement of a half-page ad for him and Al Gore in our local Valley News that was signed by yours truly and 128 others. Just 13 days before the presidential election of 1992, when he must have had a zillion other things to do, he somehow found the time to send me this letter:

October 1992 The University Press of New England publishes Representing the French Revolution: Literature, Historiography and Art, a collection of essays that I edited after hosting a conference on the French Revolution at Dartmouth in early July of 1989, 200 years after the storming of the Bastille ignited it. In his Reader's Report for UPNE, the renowned Simon Schama judged it "the best set of essays that we have" on English responses to the French Revolution, and he also found my own piece on Wordsworth's Prelude a "superlative essay, the best modern reading of the Prelude I know." On top of that a French reviewer graciously as well as Gallicly saluted "L'originalité de ce volume." Merci, Professor Patrick Berthier!

December 19, 1992 At age 98, my father breathes his last in what my mother called the "music room" of their pink stucco house on Brush Hill Road in Milton, Massachusetts, shortly after my brother Mike had visited him there for what turned out to be the last time and then driven back to his own home in nearby Needham. When Dad's nurse called Mike with the news, she said that his son Roy, who died at age 13 in 1939, had come back to tell him that it was time to go: she had recognized the boy from the photo of him that she often saw on the music room wall. I keep trying to disbelieve this story but it won't let go of my mind. At Dad's funeral mass I end my eulogy as follows--with a loving nod to a man who loved golf almost as much as he loved his wife and family, his medical practice, and the Roman Catholic Church:

Father, dear father, the Lord is your greenskeeper. He will give you a perfect lie on the emerald fairways of heaven, where the nineteenth hole is a golden chalice of eternal delight.

Father, grandfather, great-grandfather: Go now, and join your father Michael, your mother Nell, your brothers Paul, Jack, and Cy, your sisters Honot and Winifred, your firstborn son and namesake Roy, your grandson Stephen Wright, your great-grandon Justin Zachary.

For us the living, this is not a time to weep, but if there are tears, let them be tears of joy: joy for a life lived joyously, strenuously, generously--with love and laughter abounding, with highest ambitions resoundingly realized, and with all the gifts God gave to you returned to all of us like grains of wheat pressed down, shaken together, and running over.

Let no one call this death untimely. His life was a sentence magisterially wrought, and death has done no more than place the period.

At the time, I felt rather proud of this eulogy and its lapidary ending. Now it strikes me as just plain over the top--because nothing in Dad's life was so magisterial as the pretentiousness of his language, with which he infected me so deeply that to this very day I can hardly get a word of my own in edgewise.

From my mother I learned to sing such things as the London song about the muffin man who lives in Drury Lane. From my father I picked up diction that could have been coined by God's speechwriter. More than once I heard Dad drop the phrase "innocuous desuetude" as if it were yesterday's hanky tossed into the laundry basket.

Along with his diction, nothing else in his life was so magisterially wrought as his wardrobe. In the dressing room off the master bedroom of our house in Jamacia Plain, my parents each had a closet. Her little box was so crammed with dresses that I wondered how she ever found the one she wanted. His was a walk-in corridor hung with at least a dozen tailor-made suits (never off the rack) in subtly varying shades of gray, blue, and black pin-stripe.

No matter how early I got down to breakfast on a weekday morning, he would be there before me because he had to operate at 8:00, and unlike today's doctors, who spend whole working days in white lab coats or scrubs, he had to be dressed to perfection--complete with three-masted handkerchief in the breast pocket of his suit and his Ph Beta Kappa key dangling from the middle of the chain that linked the gold watch in his right vest pocket to the fob in his left vest pocket. For special occasions, he saddled his well-polished black shoes with white spats.

It was all armor--so much chained mail against anything that might challenge his iron will or steely self-assurance. In my eulogy. in fact, I said I did not know if his shining mind was ever crossed by so much as a single shadow of self-doubt. But I suspect that most people heard that as a supreme accolade.

Yet I sometimes dreamed of piercing his armor.

In his own slim memoir, called More Sunshine than Shadow, he actually mentions young Roy, but only to say that his sudden death was by God's will--deo volente. So on reading this I wrote to Dad in longhand--again and again--but each time I put the letter away in my desk drawer. I could never bring myself to mail any of them. or ever mention Roy's name in his presence.

And now, more than 33 years after his death, I see myself walking out with him to the curved stone bench at the far end of the garden outside their pink stucco house in Milton. I have taken him there so as to sit down with him and put my arm around his shoulders to see if I can somehow touch the heart that once ached with disappointment and homicidal rage way back in the middle of that hot Sunday in August of 1924 when one or more bumbling telephone operators denied him the voice of his beloved Kathleen.

I want to touch that heart now by asking him to tell me about Roy.

I want to feel the armor cracking, the ramrod spine bending, the broken heart that brokenly lived on breaking again. I want to feel him shudder. I want to hear him say how shattered he was by the death of his firstborn son, how deeply he buried the pain, and how long he had lived with it in stony silence, I want to see him smash that stony tyrant to bits.

But I was far too cowardly to do anything like that. Nancy thinks I wanted to spare him out of kindness. No, Nancy, the only one I ended up sparing was myself--out of pure cowardice.

But maybe I should console myself by recalling a moment when he actually spoke from the heart near the end of his life--not to me but to the nurse who was looking after him.

To get this story you have to know that for much of the 20th century there was a burlesque house in downtown Boston known as the Old Howard and considered among all good Catholics the gate of hell because there ladies bared their breasts and--my God!-- who knows what else?

Dad was so fastidious about everything of that kind that I was startled to learn, years ago, that as Clinical Professor of Ob-Gyn at Tufts, he told the dirtiest jokes imaginable--all in the cause of initiating medical students into the unavoidably foul and messy profession of getting their hands inside the most intimate parts of the female body.

But anyway, while he's sitting on the sofa in the TV room one night about 7 PM, the nurse walks in and tells him it's time to go to bed. To which he replies: "I don't wanna go to bed. I wanna go to the Old Howard!"

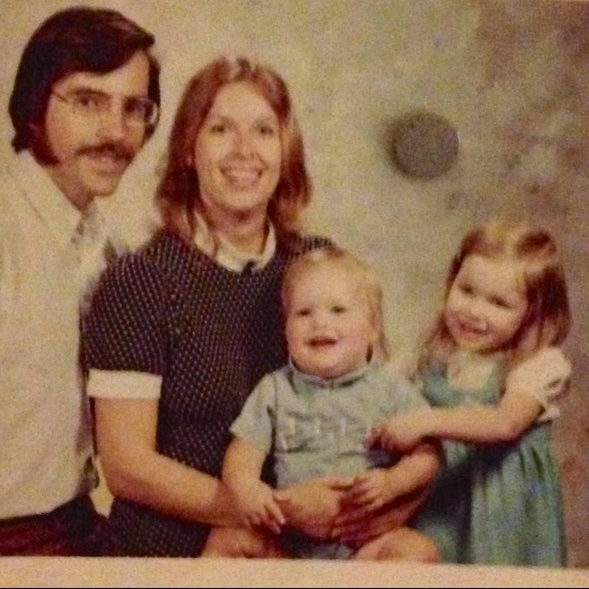

If you'd care to set all these words against just one picture, here is

Dad in his prime--a formal portrait:

Roy J. Heffernan, Circa 1950 (age 56). Photo by Bachrach Boston.

March 1993 The University of Chicago Press publishes Museum of Words: the Poetics of Ekphrasis from Homer to Ashbery. Having previously struggled to compare the work of poets and painters who knew little or nothing about each others' work, I felt much more confident in writing about ekphrastic poetry, wherein poets deliberately set out to re-create in words a work of visual art, as Keats does in his famous ode about the orgasmically aroused lovers sculpted on a Grecian urn.

December 19, 1993 The New York Times Book Review salutes Nancy's second book, which like the first was co-authored by Ann Page Stecker and published by the University Press of New England. Its full title is a doozy: Sisters of Fortune: Being the True Story of How Three Motherless Sisters Saved Their Home in New England and Raised Their Younger Brother While Their Father Went Fortune Hunting in the California Gold Rush. At once proud and yet also jealous of her coup, since no book of mine has ever been or ever will be (?) reviewed by the NYT, I nonetheless join the toast to Nancy and Ann at a little party held by UPNE to celebrate both her book and this admiring review of it.

January 1994 Hillary Clinton, whom I had introduced to her first Dartmouth audience of over 100 people on January 9, 1992, when she was speaking on behalf of her husband's candidacy for President, returns to Dartmouth for the first time as first lady. To make the case for her policy proposal on affordable health care, she addressed a capacity crowd including many doctors and other health care professionals in the Spaulding Auditorium of Hopkins Center. (Though insurance companies spent millions to stop her from reforming health care in the '90s, she worked across the aisle to help pass the Children's Health Insurance Program, which today covers 8 million kids.)

Given my past support for both Clintons, I was invited to drive in the first lady's motorcade as it travelled from Lebanon Airport to Hopkins Center and then back after her speech. My two backseat passengers included Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, who asked me my name but regrettably failed to recognize either me or my name when I briefly met him in his office some years later, (And I thought I had made an indelible impression the first time!) After driving back to the airport, I briefly met Hillary there to give her a copy of my latest book, Museum of Words: The Poetics of Ekphrasis from Homer to Ashbery as well as a copy of Nancy's Sisters of Fortune. After she hugged me a greeting, she spun me around to face a waiting photographer:

The author with Hillary Clinton. Nancy has never forgiven me for the nerdy thicket of pens sticking out my shirt pocket while I stood next to an an American icon.

I later learned that on boarding the plane, Hillary cracked everyone up by reading my inscription in the book I gave her: "To Hillary Clinton--a book that has absolutely nothing to do with health care."

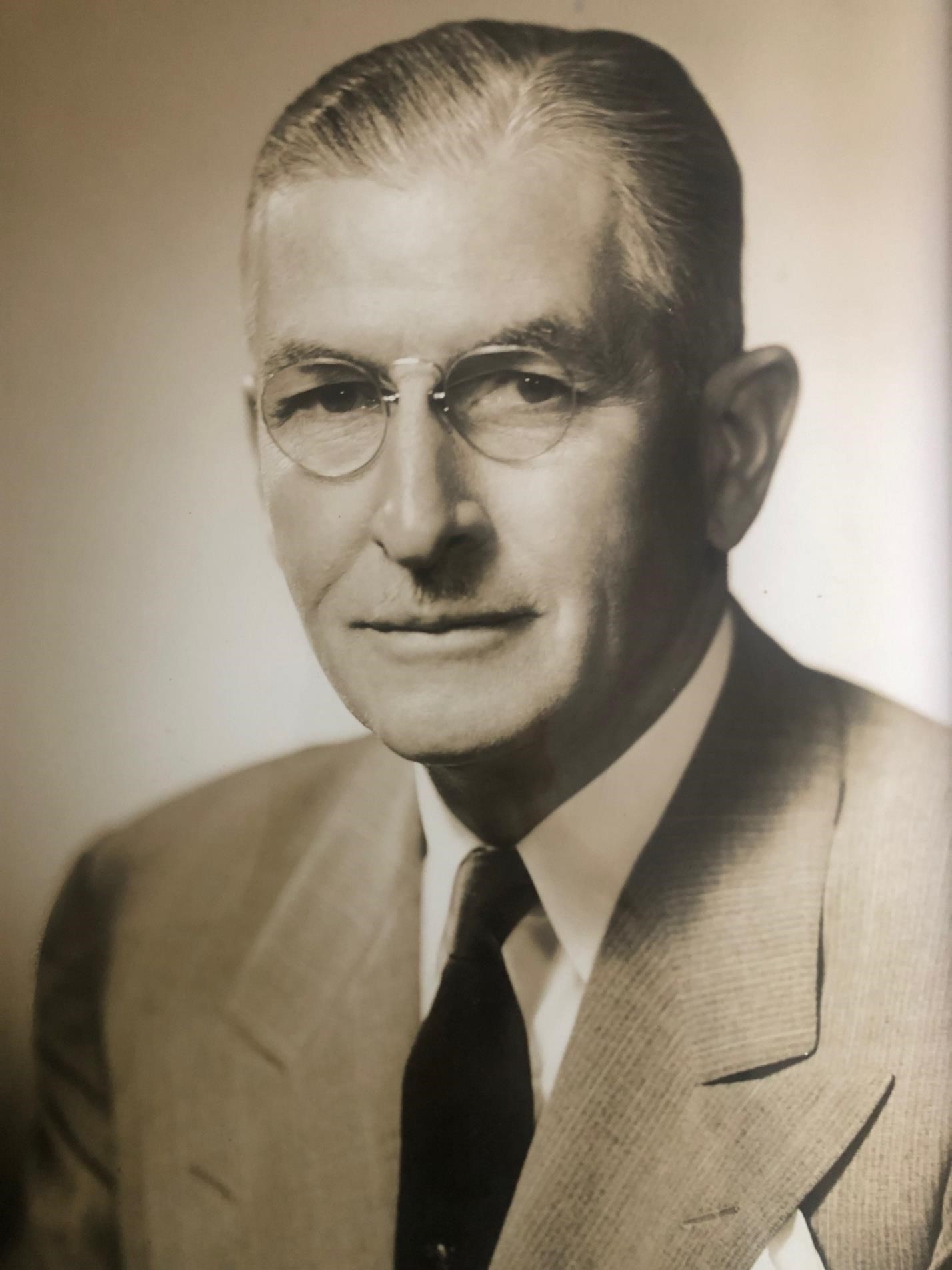

A few days after this event, she graciously sent me the following letter of thanks--not only recalling how I had served the Clinton campaign in 1992 but also citing my new book as well as Nancy's newly published Sisters of Fortune:

May 28, 1996 As his final project for the MFA at Pennsylvania State University, our son Andrew Heffernan gives a 90-minute one-man performance of Hamlet cut to ten roles and 90 minutes. For every one of those minutes I feel electrified. Easily one of the greatest thrills of my whole life.

August 31, 1997 And speaking of crackups: chauffered by a half-drunk driver desperate to elude paparazzi who were equally desperate to shoot her, albeit just photographically, Princess Diana of England and an Egyptian film producer named Dodi Fayed both die from a crackup in a Parisian traffic tunnel. I can't help remembering her wedding day (July 29, 1981) because Nancy and I were then visiting an English friend named David Lea in Camden Town, just north of Central London.

Knowing that the Earl of Spencer would take the bride along the Strand en route to St, Paul's, where the wedding was set for 11:00 AM, we three got to the Strand around 10, and though it was already jammed with crowds of other people eager to catch a glimpse of Diana, we managed to see over their heads by hoisting ourselves onto a giant spool of thick black cable that providentially happened to be standing by--as if for us. So for a few unforgettable seconds, we saw through the window of the Earl's Rolls Royce Diana's ivory taffeta silk gown spreading out over father and bride like a great white roll of California surf.

Later on, during the sunlit garden party that David gave after we had watched the wedding itself on TV, two London ladies got into a raging argument over Diana's wedding dress because one of them--herself a dressmaker--hated it.

October 12, 1998. Before an audience including the 98-year-old woman who first taught me the English language (thanks, Mom!), I try to answer the question "Who Needs Rhetoric?" in my Inaugural lecture as Frederic Sessions Beebe Professor in the Art of Writing at Dartmouth.

December 19, 1998 President Bill Clinton is impeached by the U.S. House of Representatives for "high crimes and misdemeanors"-- specifically for lying under oath and obstruction of justice regarding his affair with a 21-year-old White House intern named Monica Lewinsky. On January 20, 2001, after the Senate declines to convict him, he leaves office with a record high approval rating of 66%. (For more on this topic, see below.)

February 11, 2000 For a big family party held to celebrate the one hundredth birthday of my mother, Kathleen Walsh Heffernan, shown just above, I compose a free verse narrative of her life, which was not only long but exceptionally full. Besides having nine children who in turn begot 32 grandchildren followed by 44 great-grands, she had many adventures. In the summer and fall of 1920, after France had been ravaged by World War II, she went to work in Soissons, 60 miles northeast of Paris, for the Comité Américain pour les Regions Devastées de la France. In late December, after six months of learning the language, showing young children by day how to exercise, and teaching older ones in the evening how to dance, she was awarded a silver medal. In her fifties, she was twice the Women's Senior Golfing Champion of Massachusetts. And at age 95, as shown below, she realized a lifelong dream by taking a glorious balloon ride one sunlit early morning, courtesy of two generous grandsons (photo below). In the poem I called this tall and lovely woman a "long-stemmed rose." In late January of 2002, when her coffin was lowered into the grave, her 32 grandchidren laid on it 32 long-stemmed roses.

December 12, 2000 The Supreme Court stops the counting of Florida votes in the presidential contest between Vice President Al Gore and George W, Bush, Governor of Texas, making Bush the winner in the Electoral College even though Gore had beat him by 543,895 in the popular vote. On December 13, Gore declares, "While I strongly disagree with the Court's decision, I accept it."

September 11, 2001 On the very day and at almost the same time that Nancy and I see for the first and only time in our lives the ancient city of Troy in Hisarlik, "Place of Fortresses" near the Aegean coast of Turkey, two planes piloted by Saudi Arabian highjackers hit the nearly top floors of the two World Trade Towers in New York City, shortly sending them down through clouds of smoke and flame, and one more hits the Pentagon in Washington. Having long before read and studied Virgil's account of the flaming fall of Troy in the Aeneid, I can't help linking these two ruinous events across the 32 centuries stretching between 9/11 and the year 1200 B.C.E or thereabouts, when Troy actually fell.

But we get reliable news only after reaching our hotel in Çanakkale, where we learn that the front desk had already been called by our daughter Virginia, who then lived near the Brooklyn Heights promenade (and still does) but worked for the New York Times. Had she gone to the NYT that morning, her subway ride would have taken her right under the burning towers. Since phoning Turkey would shortly become impossible, she wanted us to know right away that she had got the fearful news just in time to keep safe at home, and the desk man had put her on speaker phone so that she could update everyone there.

We later learned that while we spent much of the night in our hotel room glued to CNN's coverage of the burning towers, she had spent much of the afternoon on the promenade watching papers of all kind floating across the East River like the fluttering dead leaves of autumn.

June 7, 2004 On my retirement from the Dartmouth English Department after 39 years in it, I am honored by a dinner served in the Library of

Sanborn House, the stately Georgian home of the department built in

1928. For the occasion I compose a long, clunky parody of

Wordsworth's "Tintern Abbey" that begins and ends as follows:

Thirty-nine years have past; thirty-nine summers

And the length of thirty-nine very long winters . . .

. . . and in after years,

When these wild ecstasies shall be matured

Into a fine senility, when your minds

Shall be a warehouse of all the wretched papers

That you ever graded. oh then!

If yet another Wall Street crash

Should devastate your assets, with what healing thoughts

Of tender joy will you remember me,

And these my exortations!

Of course I didn't remember to behave myself. Drinking more wine than

I should have at my age, I awoke next morning with something I thought

I had long left far behind me: a bleary-eyed hangover. What can I say?

I've always been a slow learner.

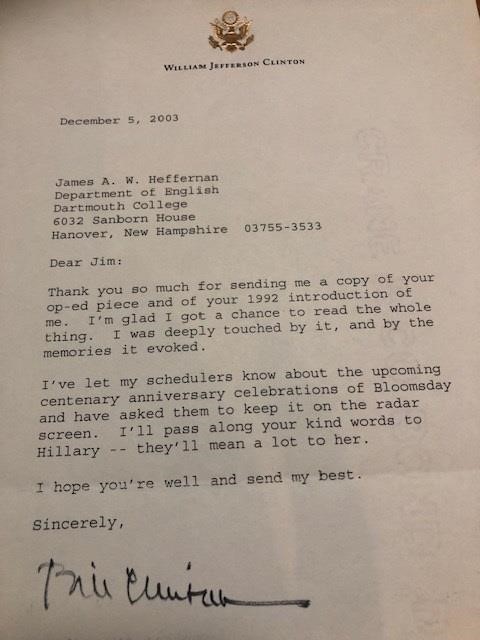

December 5, 2003 The now former President Bill Clinton thanks me for sending him at long last the full text of my introduction of him to his first Dartmouth audience just before the New Hampshire primary of February 1992 as well as for defending him against his detractors in an unpublished oped that I had also sent him:

Since he was "deeply touched" by my introduction "and by the memories it evoked," here's the full text of what I had to cut to just its final paragraph back on the momentous night of Bill's first speech to a Dartmouth audience.

He didn't make the Bloomsday centenary, but I was glad to know he thought about doing so, since I had sent him the videotapes of my lectures on Ulysses.

In the unpublished oped, I argued that in spite of its disgracefulness, Clinton's affair with the 21-year-old Monica Lewinsky did not justify his removal from office, any more than Alexander Hamilton's affair with a 23-year-old married woman named Maria Reynolds in 1791-92--even when compounded by a husband who blackmailed Hamilton for his silence--ever lost him the respect of George Washington, who still held him in "very high esteem."

The upshot of the Lewinsky affair, however, was heart-wrenching and heart breaking even though also--in one way--heart-warming. On one hand, the U.S. Senate declined to convict Clinton after he was impeached in the House, and he left office with a record high approval rating of 66%--a stunning tribute to all he had done for our country during his presidency, On the other hand, his affair with Monica led Kenneth Starr and his gang of cunning hired knaves (including Brett Kavanagh, later elevated to the Supreme Court even after being plausibly accused of attempted rape) to spend forty million hard-earned taxpayer dollars getting their investigative fingers into Clinton's underwear so as to rub our noses in their sordid picture of his unzipped rigid phallus being more than once mouthed by Monica.

Though accused of lying when he testified under oath that he had "not had sexual intercourse" with her, he was actually just within the bounds of strict truth. But the Starr report blew a hole in the presidential campaign ship of Al Gore, who would otherwise have surely sailed right into the White House and spared us the saga of the cliff-hanging, hanging-chad vote counting mess in Florida that the Supreme Court "resolved" by handing down an equally messy verdict on behalf of George W. Bush. It is heart-breaking to realize that if all the Florida votes had been fairly counted, Al Gore might also have spared us from invading both Afghanistan and Iraq and thus saved hundreds of thousands of lives (American and otherwise) as well as the trillions we have spent in our blind, unholy, and unending War on Terror.

But the mess of the Florida recount was not the first cause leading to that war, Ultimately, it can be traced to a few encounters between a president and a smitten intern in a White House corridor. There is no decent way to state this simple truth about the ultimate impact of the Lewinsky affair: in the long and winding riverbed of history, it is surely the first time in which the course of human events in the world at large was almost certainly made to swerve by a few blow jobs.

25 September 2006 Baylor University Press publishes Cultivating Picturacy, a collection of my essays on the relation between literature and art. I belatedly realize that the title is needlessly pretentious as well as neologistic, for it could simply have been called Reading Pictures, the title I used for a follow-up essay published some years later in PMLA. Since the book includes an essay on the rhetoric of art criticism from ancient times to our own (previously published in a journal called Word & Image), and since that essay concludes by saluting the work of Leo Steinberg, a renowned art historian whose books I greatly admired, I sent him a copy of the essay, which he graciously found both "eloquent and provocative."

I dedicated the book to W.J.T. Mitchell, the reigning master of interart theory and criticism, who is also a longtime friend. The book was generously received by several reviewers including Gillen D'Arcy Wood, who called it "a treasure for scholars and students interested in the history, theory, and practice of text-image relations." Thanks, Gillen!

September 2009. As Founding Editor I launch the online Review 19 (www.review19.org), which reviews academic studies of nineteenth-century British and American literature. To date (March 2024 as of this writing), thanks to hundreds of reviewers ranging from graduate students through emeriti like me, we have posted nearly 700 reviews and drawn over 200,000 unique visitors. It is now edited as well as digitally managed by Andrew Foust.

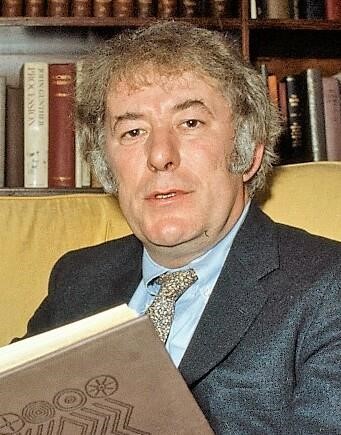

30 August 2013 Death of Seamus Heaney, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995. Sometimes called the rock star of Irish poetry (at his death The Independent called him "probably the best-known poet in the world"), he was actually a supernova beyond any comparison with lesser stars and their petty pretensions, of which he had not so much as a microbe.

I first met him in the winter of 1990, when he was based in Cambridge, Massachusetts as Poet in Residence at Harvard, and came up to Dartmouth to give a reading of his poems as well as a lecture on Joyce's Ulysses--"Dublin doubled," he called it--which I eagerly attended because I was just about to teach a Senior Seminar on this monumental novel for the very first time. Without getting into details, I can report that his lecture was somewhat informal but also delightfully personal and utterly captivating. (One line I remember re Joyce and Yeats: "Joyce lived for a few days in a Martello Tower rented by someone else; Yeats owned a tower!"

Now here's a sample of Seamus's utter disdain for pretension. In the spring of 1998, when I met him at a conference on Wordsworth in the Lake District of England and told him how much I had enjoyed his lecture on Ulysses at Dartmouth, he threw his great head backward and sputtered, "That was ludicrous!" How could he possibly presume to give a lecture on Joyce?

But in fact he was a brilliant critic of literature as well as an incandescent poet himself, and as soon as I read his essay on an 18th century poem by Brian Merriman (of whom I had never heard before) in The Redress of Poetry (1995), I suddenly realized that it held the key to Molly's monologue at the end of Ulysses--and promptly wrote a paper on it that later appeared in the James Joyce Quarterly.

Meanwhile I corresponded with Seamus occasionally. Since he was born on April 13, 1939, precisely nine days before me, I actually began to think of him as my literary twin brother (though of course I never told him that) and felt free in particular to tell him about our very first grandchild, Kate Robin Heffernan. When Kate was not yet 3 years old, her father Andrew started reading poetry to her, and since Andrew (like me) is a great fan of Heaney, the poems included "Postscript," which was inspired by what Heaney saw one day as he and some friends were driving along "the flaggy shore" of County Clare, with the whitecapped Atlantic on one side of the road and on the other a pond all lit up with the whiteness of swans: a sight, the poem ends, to "catch the heart off guard and blow it open."

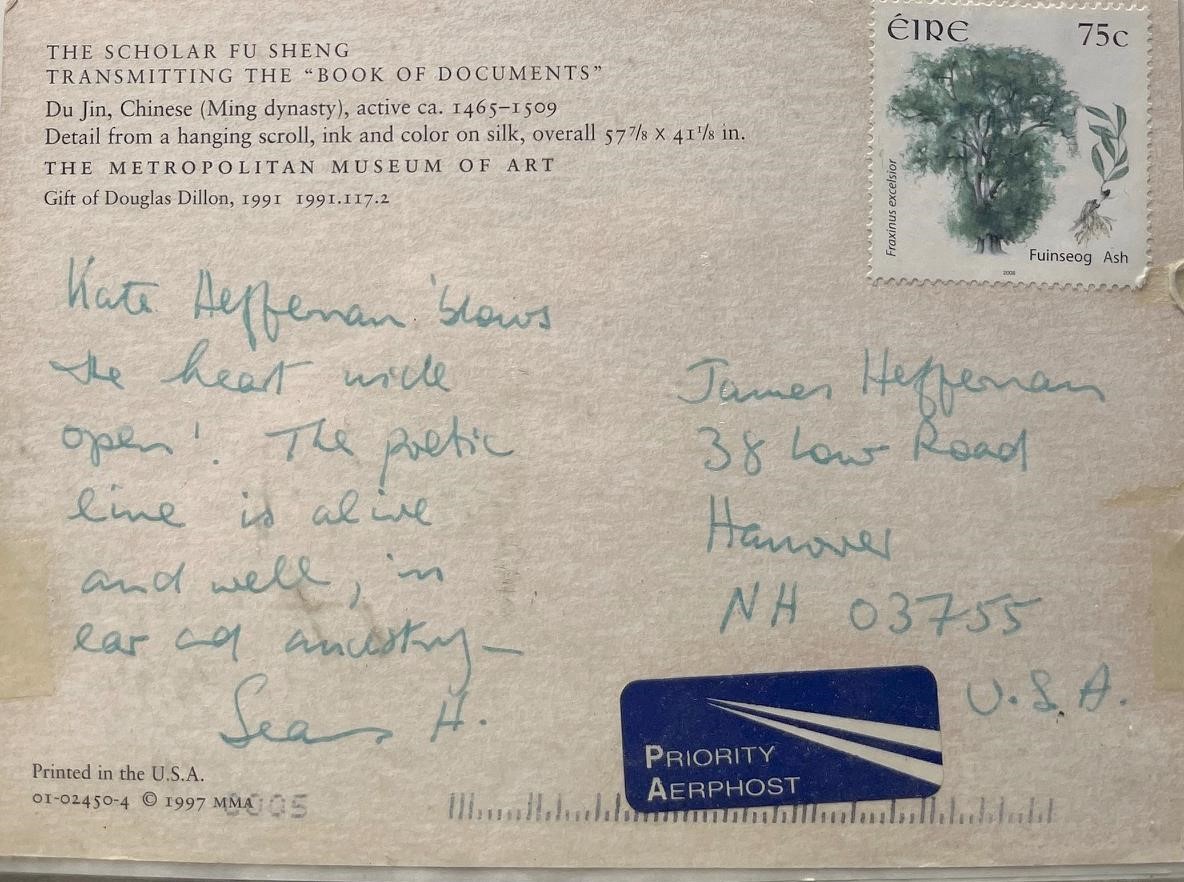

When I wrote to Seamus that our two-and-a-half-year old Kate had not only heard the poem recited by her father but had also recited it--or much of it--back to him, Seamus replied by handwritten postcard:

"Kate Heffernan blows the heart wide open! The poetic line is alive and well, in age and ancestry --Seamus H."

In late August 2013, when I learned of Seamus's death, my own heart was blown wide open by what I learned were his last words, "Noli timere." And when I later learned that my daughter Virginia had actually purchased a work of art inspired by those words, I felt impelled to write about them--partly because they spoke so powerfully to my own lifelong love of classical Latin:

NOLI TIMERE

for Seamus Heaney

On a wall in my daughter Virginia's Brooklyn apartment

hangs a work of art wrought by Deepa Mann-Kler:

a neon sign of faith.

Shining white against a coal-black rectangle of wood,

its words radiate something

darkness will never grasp

even if the plug is pulled,

even if the whole borough's power grid

all at once fails.

Noli timere.

Do not fear,

Have no fear.

Do not wish to fear.

Do not even think of being afraid.

Whatever they might mean in English,

they were the last words Seamus Heaney

texted to his wife Marie from a hospital bed in Dublin

just before he died at the age of 74

on August 30, 2013.

He thus foresaw the dying of the light,

the coming of the night

without fear

and without rage.

Of course he could have tapped out English words

or flashed one final Continental wave

with "ti amo sempre" or "au revoir."

Better still, he could have tapped deep down his well of Irish

words:

the language spoken centuries ago

by the fathers of his fathers' fathers' fathers,

before the strangers ripped it from their mouths

tearing out their tongues at the root.

But leaving those roots unstirred.

he felt instead the tongue

of the much older strangers

who sailed to Britannia two thousand years ago.

and whose words must have struck fear

in everyone who heard them,

whether Celt or Caledonian, Gael or Gaul.

"Timete nos!" The Romans must have said.

Fear us!

"Cedite vel morite!"

Give up or die!

Four centuries later, the Roman Empire died.

Yet its tongue endures

throughout the English-speaking world

in roots that sink so deep

inside the words we speak

that we could sooner wipe away

all traces of our DNA

than rip out all the Latin from our speech.

So "timens" lurks in "timid,"

"lumen" in "luminous,"

And "monumentum" leaves its monument for all to see.

It stands right up there in the nearly final words of Horace,

the ancient Roman poet whose friends and fans included--inter

alia--

Augustus, Emperor of Rome.

Horace went out with a flourish.

After writing many poems of many kinds--

odes, epodes, satires, epistles, and the Ars Poetica,

his lyric treatise on the art of poetry--

he proudly told his patron, Maecenas,

"Exegi monumentum aere perennius."

"I have built a monument more lasting than bronze."

The death of Horace was shortly followed by the birth of Christ,

who grew up to build a monument of faith.

One day in the deepest part of Lake Gennesaret

he calmly calmed the fears of Simon Peter

when, having netted scores of fish with James and John,

he felt their overloaded boats were sinking--for his sins.

But in the Roman tongue of St. Jerome, Christ told him,

"Noli timere."

Seamus Heaney never claimed

that he had built a monument of any kind.

But in negating timere,

in echoing Christ,

his own last words

said something bolder:

I have shone a light more lasting than darkness.

It cannot fade.

It will not die.

Have no fear.

October 2021

May 27, 2014 Yale University Press publishes my Hospitality and Treachery in Western Literature. Having taken about ten years to write, it is reviewed nowhere in print and online just twice, one of which two I commissioned for Review 19. But it has so far sold around 650 copies.

June 27, 2014 Nancy and I celebrate our Golden wedding anniversary with dinner and dancing for about fifty people on the terrace of the Lake Morey Inn in Fairlee, Vermont, about 20 minutes drive north of Hanover via Route 91. Miraculously, the threat of rain abated just in time for us to hold the party outside under the stars, with the lake waters sparkling beside us. Though Nancy thought that hardly anyone of our aged friends would dance, the live band led nearly everyone--regardless of age--to do so, and besides a giggly performance by our four grandchildren (then aged 5 to 1l), I myself stood at the mike and croaked out "As Time Goes By," the ageless theme of Casablanca. I also offered the following toast to Nancy:

FOR NANCY ON OUR FIFTIETH WEDDING ANNIVERSARY

Full fifty years ago this very day,

You smiled at me and sweetly said, "OK."

Well--not exactly that, my dear, it's true;

To be precise, you spoke the words, "I do."

And what you did was pledge for all your life,

To be my lawful, faithful, wedded wife.

So first we settled in Virginia,

Where you thought we would live forever--hah!

Instead I dragged you all the way up here,

Where ice and snow besiege us half the year;

Where spring brings mud in great long filthy streaks,

And summer, if you're lucky, lasts six weeks;

Where autumn leaves soon turn to bare ruined choirs,

And winter drives us desperate to our fires.

Yet braving all the weather of these years,

You've borne up with a minimum of tears;

You've cooked our meals with never-failing grace,

You've made our home a most inviting place;

You've also found the time to teach and write,

To bring us all your special brand of light.

Till you and Ann Page plumbed the mystery,

New Hampshire scarcely knew it had a history;

And when you wrote about the sisters three,

The New York Times applauded--strenuously.

And now your tale of sisters and their plight,

Of Betty's trials and Hannah's desperate flight,

Has made us realize what we never knew--

That such a gruesome story could be true. [SEE FOOTNOTE]

On top of that I cannot fail to see

How much you've done for our own family:

You've been a supermom to both our kids,

Supporting them in everything they did.

And having raised both Andrew and Virginia,

You've proved yourself a sterling grandmamma;

For you can never sate your appetite

For grandchildren who fill us with delight:

For Ben and Dylan, both of whom are great,

For sweet Susannah, and for charming Kate.

So I give thanks for all you're fashioned of,

For years of laughter, friendship, warmth, and love.

As I stand here and lift my glass to you,

I'm very glad that you once said, "I do."

*FOOTNOTE

Nancy has not only co-authored two books on New Hampshire history, including Sisters of Fortune (saluted by the New York (Sunday) Times Book Review) but also singly authored a novel (Blood Sisters) about Hannah Dustan, a New England colonial wife and mother captured in 1697 by Abenaki Indians and held until she made her escape by killing an extended family of them as they slept, tomahawking them with the aid of the midwife who had just delivered her newest child--a child they had killed. See what I mean by "gruesome"? Betty--Hannah's sister--was tried, convicted, and hanged after her illegitimate twins were found dead and buried outside the house of her parents, where she was then living while also denying that she was pregnant.

June 5-10, 2019 For the first time ever, Nancy and I take our whole gang--two kids, one spouse (Virginia was temporarily single), and four grandkids--on a five day safari in Tanzania, riding in two Land Rovers through Ngorongoro and its mighty crater and around the Serengeti, which--our guide explained-- means "endless plain," but which I at first mis-heard as "endless play," Our play felt endless, and it was easily the best family trip we've ever taken--before or since. How could it fail with sights like this gazelle?

Or these gazelles?

In fact, as soon as we spotted our first elephant crossing just in front of us on the very first day of our trip--

we were all hooked. Our two Tanzanian guides were so good and so eager to make sure we saw every possible animal they knew about that we have kept up with them ever since--especially since safari tourism fell off drastically after COVID struck in the spring of 2020, leaving almost all safari guides in Tanzania out of work. One of them-- Joseph Sandilen Kivuyo, who was born in a Masai village to a father with something like 20 wives and scores of other children, got himself educated in a Christian school and has a daughter named Norah, who is seeking a degree in pharmacology from the College of Pharmacy of the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center in Moshi City, Tanzania. When we learned that her tuition was just $2500 a year, we decided as a family to fund her three years there.

Here's the author having the time of his life on safari:

June 24, 2022 By a vote of 6 to 3 in the case of Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health, the U.S. Supreme Court overturns nearly fifty years of precedent (starting with Roe v. Wade in 1973) by ruling that the Constitution does not guarantee a right to abortion and therefore that states are perfectly free to regulate it and/or criminalize all abortions--with no exceptions even for pregnancies caused by rape or incest, or even when termination of a pregnancy is --in the words of RJH and Lynch- - "the undesired, unintentional and inevitable result of the radical attack on the malignant disease"--in which case, they say, it is "not a therapeutic abortion."

But for all I know, 8 states would prosecute doctors for performing just this kind of operation. Do you really think, Dad, that state governments should have the power to oversee and overrule decisions made by obstetricians in cases like these? That obstetricians in Texas should be prosecuted for terminating a pregnancy at anything short of death's door for the woman involved? That a pregnant woman whose waters have prematurely broken and whose fetus has absolutely no chance of surviving must nevertheless be forced to carry it to term? Or that a 10-year-old girl impregnated by rape should be forbidden to abort her fetus by Ohio state law, which meant that she had to leave the state to find relief ?

Almost as much as you hated abortion, Dad, you hated any kind of government interference with the practice of medicine. So perhaps it is just as well that you did not see live to see what has become of obstetrics--your beloved profession--in states like Texas. Consider where we are now in light of this passage from your article:

Pregnancy is a troublesome complication in the women suffering from chronic nephritis or hypertension. However, most of the serious difficulties that arise in the patients develop after the period of viability. Prior to this, miscarriage frequently occurs and nature thereby solves the problem.

In other words, Dad, miscarriage means that nature terminates the pregnancy--right? And since you firmly believe in God, you would at the very least admit that God allows the "natural" termination of a pregnancy whenever a disease such a hypertension makes it necessary--right?

But would you still insist that no obstetrician--no matter how thoroughly experienced--should ever be allowed to terminate a pregnancy? So that even if there was absolutely no chance of a live birth and / or no chance of a viable infant, an obstetrician working in Texas, would have to choose between letting this pregnancy run its possibly fatal course (for mother and/ or baby) or risking prosecution for aborting it?

Or do you not now, at last, find the Dobbs decision an intolerable insult to the rights of pregnant women and their doctors to act as freely as their own consciences and their own best medical judgment allow? Please, Dad: search your own conscience, and listen to the voice of your own heart.

December 21, 2023 My latest book, Politics and Literature at the Dawn of World War II, published by Bloomsbury Academic the previous December (though copyrighted 2023), is praised at length in the New York Review of Books which is probably the toughest nut an academic book can hope to crack. To this moment I remain thrilled. (For more on what led me up to the writing of this book, see Chapter 1.)

November 13, 2023. The Valley News, our local newspaper, publishes my oped, "Are We Getting it Wrong on Prostate Cancer Screening?"

The oped explains just how the widely circulated advice of the US Preventative Service Task Force (advice dangerously wrong but still thriving, unlike me) led me to stop getting tested for prostate cancer in 2012 and thus give it plenty of years to invade my skeleton until finally detected in 2017--as stage 4 metastatic prostate cancer.

After five years of managing fairly well with hormone therapy (aka "chemical castration"!), I was diagnosed as a terminal case in late September of 2023, and am now in hospice care. In response to the many emails and visits I've had from kind and sympathetic friends, I tell them that I feel perfectly calm after a long and burstingly full life of 84 years. that I am being treated like a king by Nancy and the children, and that I still have marbles enough in my head to write this memoir, which has been great fun because the deep well of memory has proven a geyser--as I hope by now you can see for yourself.

January 2, 2024 After just six months and two days in office, Claudine Gay resigns from the presidency of Harvard. For almost three months, the first Black person ever to hold this office had survived the little war on Ivy League university presidents waged by Republicans bent on routing their supposed tolerance for anti-semitism on college campuses, But on December 21 the New York Times reported that in Dr. Gay's 1997 doctoral dissertation, Harvard found two examples of "duplicative language without appropriate attribution"--on top of the two published articles that Harvard had already found in need of additional citations. Twelve days later, she was made to step down.

In light of this regrettable story, I re-examined the whole concept of plagiarism itself. Setting aside the new seductions of AI and ChatGPT, which really offer a whole different can of worms, I set this case within a brief history--the hair-raising history of celebrity plagiarism. But since I was unable to place it anywhere except on my own website (too hot to handle?), that's where you'll find it--if your fingers are brave enough.