CHAPTER 2. FROM GEORGETOWN TO UVA

On entering Georgetown's College of Arts and Sciences (CAS) in the fall of 1956, I joined an all male, all white, and nearly all Roman Catholic class of 212 students. (I remember precisely one Jewish classmate, and we were always addressed as "Gentlemen of Georgetown" by GU's President Edward Bunn, a squat and savvy Jesuit who--except for the clerical black of his suit--always struck me as looking and sounding like nothing so much as a talking fire hydrant.)

Since my time in it, the CAS has dramatically grown. Besides more than doubling the size of each entering class, the College now takes students of all colors, races, creeds, sexes, and maybe genders too (though I don't know about transgenders). As a result, its acceptance rate has plummeted. During the years in which I spoke (as one of many "alumni interviewers") with something like forty applicants, I recommended many, but only one or two of them got in. In the early fifties, a Roman Catholic applicant to Georgetown who could write his own name and whose parents could pay the tuition (then about $1700, that's seventeen hundred dollars) was probably at least halfway there.

Fortunately, I once again lucked out with a place in the Honors group of my class. Given the dominance of STEM fields now, it's hard to believe how little we studied them. With just one course on set theory in mathematics (a course specially designed for clueless innumerates like us), we otherwise studied philosophy and literature, in which eventually I double-majored. Though I ended up pursuing literature, I loved philosophy, and in my sophomore year I had an epiphany of sorts while writing a long paper on "The One and the Many" in the Platonic dialogue called Thaeatetus, Years ago I chucked the paper out in a radical purge of our basement, but I can still remember one of its sentences: "To understand Plato we must walk a slender tightrope, as wary of the univocism of Parmenides as of the impossible relativism of Protagoras." And of course I remember the grade: "A resounding A-plus, but you're still over-writing." Which indeed I was.

Tall, Scots-blooded, highly kinetic (he almost always walked or rather jerked around in front of us rather than teaching from the chair behind his desk), and immensely stimulating, Professor Thomas P. McTighe specialized in Nicolas of Cusa, "arguably the most important German thinker of the fifteenth century" and did not pull his punches. Whenever he returned a stack of our papers, he would invariably diss the "goddam women English teachers" who had already corrupted our styles. In spite of his casual misogyny (rampant in the 1950s, now an all-but-mortal sin), he gave me once some very good advice. When I told him I was thinking about going into advertising or journalism, he said, "You should be a humanist." For playing even the tiniest part in my decision to do so, I owe him my heartfelt thanks. He died in 1997, and via Google I have just learned that in his honor the McTighe Prize is now granted to a top GU senior every year.

For recreation at GU I joined the Glee Club, which was then conducted by Paul Hume, who was also music critic for the Washington Post and probably best remembered now for daring to fault the singing of Margaret Truman at a solo concert in Constitution Hall in December 1950. He thus provoked from Margaret's father Harry a letter in which, among other things, the give-'em-hell president threatened to sock him in the eye. But since Hume greatly admired Truman, he cherished the letter as a prize possession.

I sang base under Hume for all four years of my time at Georgetown. A charming taskmaster who could be funny and fun even when scolding us for sometimes ignoring his baton (he would punctuate his short rants by banging the piano keys), he never ceased to amaze me with the rich totality of sound he drew out of our separate voices. In the spring of 1957, we sang for President Dwight D. Eisenhower during his visit to the School of Foreign Service, and I'll never forget the gleam of Ike's broadly smiling bald head as we belted our lungs out for him.

We rehearsed several times a week, and though I must confess that I never really learned to read music and had to pick up notes by just earing the other guys in my section, I loved to sing. By late afternoon on rehearsal days, I welcomed the break from reading and writing as well as the sheer pleasure of learning some great choral pieces such as Flor Peeters' Te Deum, Antonio Lotti's exquisite Crucifixus, and best of all, the magnificent Sanctus from Bach's B Minor Mass. While all of them helped me to feel the musicality of the Latin language, which I had up to then studied but scarcely heard, I best remember the time we first rehearsed the Bach Sanctus along with the women's chorus of Manhattanville College. Since most of us had never heard it with all sopranos and altos as well as our own bases, baritones, and tenors, the glorious blend of all those voices was a revelation. We finished by applauding ourselves--and the mighty Johann too--in sheer joy.

In my sophomore year, the Glee Club included a freshman in the School of Foreign Service named Paul Pelosi. He is now best known as the husband of Nancy Pelosi, the Democratic Representative from California who served with great success as Speaker of the House at two different times from 2007 to 2023. Though I barely knew Paul at the time, I remember two things. One was the fit of his shirt collars, which must have been tailor-made because they encircled his neck so precisely. (My ready-made shirt collars were almost always too loose or too tight.) The other was his raving about the beauties of Lake Tahoe in California, where he grew up. Since he eventually became head of a real estate and venture capital investment firm based in San Francisco, I have sometimes imagined his acquiring a sizable stretch of Lake Tahoe shoreline.

But quite apart from that, I was horrified to learn of what happened to him in his own house in San Francisco on the night of October 28, 2022, when he was struck on the head with a hammer that fractured his skull--thanks to a deranged conspiracy theorist bent on kidnapping Nancy, who was luckily in Washington, DC at the time. Though he has since been slowly recovering, I gather that he still suffers headaches and bouts of light-headedness. One more sign that the freight train of our partisan politics has jumped the rails.

Besides singing, I did some acting. As a freshman I played Lane the butler in The Importance of Being Ernest (which neatly introduced me to a play that I would later lecture on for the Teaching Company), and as a sophomore I landed the part of Brutus in Shakespeare's Julius Caesar. My performance was hardly brilliant. Though deftly guided by Donn Murphy of the GU Drama Department, who later won a Best Director Award from the DC Theater Alliance, I never really got inside the mind and heart of Caesar's would-be noble assassin. But the fault may not have been wholly mine. As I later realized, or at least concluded, Brutus is a prig, and it's pretty hard (sorry, Mr. White!) to make a prig sympathetic.

I must add that since GU in the 50s required all its "gentlemen" to wear coats and ties to all classes and other formal functions such as masses and class assemblies in Gaston Hall, we had our share of peacocks. Two of them, whom I will call simply Jack and George (mercifully suppressing their surnames) cast themselves as the sartorial heirs of Beau Brumell, the legendary dandy of English Regency fame. Clad in threads impeccably woven by the Brothers Brooks and mostly purchased from the wildly-expensive-but-worth-every-penny Georgetown Shop (the sole emporium of young men's clothing in Georgetown at the time), Jack and George spent much of their time seated together just outside Ryan Cafeteria, chatting with each other and displaying one after another tweed coat, starched pin stripe shirt, regimental striped necktie, and razor-creased pair of grey flannels that were all reputedly changed several times a day. Now and then they sniffed as guys like me walked past them in our shabby jackets, wrinkled shirts, ragged neckties, and rumpled khakis--all in the cause of complying only with the letter of the coat-and-tie rule. (I can't recall anyone's actually wearing a coat and tie over a bare chest and bare legs, but I sometimes put my own bare feet into a pair of dirty white bucks.) I should add that George's disdain for my threadbare outfits extended to my performance of Brutus, which he roundly thrashed in a letter to the Hoya that struck me just a little unfair.

And what of politics at Georgetown? Like many other leading universities in this country for many years, GU has been periodically caught up in political battles, as it was over the war between Israel and Hamas. But in the 1950s, Georgetown was mostly an apolitical hotbed of student rest: long on parties, drinking, and polo (no football in those days!), short on ideological feuds. Though my classmates included Patrick Buchanan, who later became a paleoconservative stalwart of the pre-Trumpian Right (as well as twice running for president in 1990s), I can't recall a single argument--let alone a stormy protest--over partisan politics, unless you count the punch that the pugnacious Buchanan reportedly gave a cop sometime during our freshman year.

But since Georgetown is just a few miles from the U.S. capitol, I would occasionally cut class to see what our lawmakers were up to there. In March of 1957 I attended some of the hearings of a U.S. Senate committee that was probing various kinds of illegal activity by the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. Chaired by Democratic Senator John McClellan of Arkansas, the committee included then-Senator John F. Kennedy, with his 32-year-old brother Robert serving as its special counsel. I will never forget the childishly high pitch of Robert's voice as he relentlessly quizzed Dave Beck, then President of the Teamsters, who invariably took the fifth in response to every question--exercising his Fifth Amendment right to decline to say anything that might incriminate him.

During a break on one day of the hearings, while I was sitting in the front row of the gallery (I'd managed to land a good seat by coming early to the caucus room), I fell into conversation with the trim, lively, dark-haired woman who had been sitting beside me. As soon as she learned that my name was Heffernan and that my father was Dr. Roy Heffernan of Boston, she introduced herself as Ethel Kennedy, Robert's wife, and raved about what a wonderful doctor my father was. (He had many admirers among his patients.) She even floated the prospect of having me out for dinner sometime at the Kennedy house on Hickory Hill. And a little later, when Joe and Rose Kennedy turned up at the end of the hearing, she introduced me to them and we all shook hands.

I then stood with the Kennedys for a moment just to imbibe the champagne fizz of their propinquity, I suppose, until Ethel turned to me and said, "What are you hanging around for? We can't give you a ride or anything." Her own champagne had suddenly evaporated, and I never heard from her again--nor ever thought I would.

Three years later, in late January of 1960, when John F. Kennedy was running for president in the Democratic state primaries, I went to his Senate office with my roommate Tom Allen and a few other Georgetown students for a publicity photo to help advertise our student show, a zany musical written by one of our classmates (more to come on him below), Before our photographer snapped Jack with all of us on either side of him, Tom (a born hustler who had arranged the shoot) introduced me to the senator as the son of Dr. Roy Heffernan, which prompted JFK to say, "Oh yesh, Bobby"--meaning of course that he knew my father had been delivering the babies of Bobby's wife Ethel. They included Robert F. Kennedy, Junior, whom dad delivered in 1954 and who is now running as an Independent for President of the United States. Nine years later, Dad was photographed with RFK Senior just after delivering another addition to the family:

Senator Robert F. Kennedy with Roy J. Heffernan at St. Elizabeth's Hospital in Boston on July 5, 1963, the day after Roy delivered Christopher Kennedy, Robert and Ethel's eighth child.

OK: back to JFK's office in late January of 1960. Between the introductions and the photo shoot came a short break during which the senator prepared himself in a way that I wish to record here for the special benefit of historians. My source is the impeccable memory of a classmate named Paul Janensch, who not only produced the student show we planned to advertise with the JFK photo but also later became Executive Editor of the Louisville Courier-Journal (Wikipedia). During that memorable day back in late January of 1960, Paul distinctly remembers walking by a restroom in the senator's office and seeing the door half open. Standing in front of the mirror, JFK was preparing himself for the photo shoot by carefully fluffing his hair.

As for me, I not only got to shake his hand but even worked up the courage to ask him a question about how long he thought a Southern filibuster against a then-pending civil rights bill would last. ("Oh, 'bout a week," he said.) Shortly after, he flew off to campaign in Wisconsin, where he won the primary--one of many that led to his triumph in July of 1960 at the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles, and ultimately to the White House.

To my great regret, I never got a copy of the photo that was taken of me and the others with the future president.. My only souvenir of the occasion was a pass to the senate signed by JFK--or maybe robo-signed, for all I know:

As for the photo, I don't know if it was ever used to publicize the student show. (What good would it have been, anyway?) But in my mind's eye I can still picture the whole encounter, which probably took less than fifteen minutes.

Just before we all left Kennedy's outer office, whose walls were crammed with framed photos of his whole clan, a classmate named Danny O'Neill asked to be photographed shaking hands with Jack. Since Danny's father was a Democratic Party delegate from Illinois, as I think Tom pointed out, Jack agreed to the extra photo, but since our photographer was standing behind Jack with Danny on the other side, facing him from against the wall, there was no easy way for them both to face the camera in the crowded office. Then someone reminded everyone that Kennedy could be recognized from any angle, front or back. So the photographer aimed his lens over Kennedy's shoulder to the face and extended arm of Danny shaking the future president's right hand.

While shaking Danny's hand, Kennedy was flanked by two of his aides, one facing him from the left and the other facing him from the right. Putting his left hand on the right shoulder of the one on the left, to keep him close, he looked to Danny's right and spoke directly to the other aide, no doubt about the campaign. Throughout this three-point contact, he was cucumber cool, calmly transitioning from an inconsequential photo shoot (though his favor to Danny might have paid a small dividend in Illinois) to the most important business of his life just then: winning the Wisconsin primary.

By this time in my senior year I had applied for a Fellowship-- to fund my first year of graduate study in English--from the Woodrow Wilson Foundation, now called the Institute for Citizens & Scholars, which has thus expunged the name of the slave-owner who flunked my grandmother Marian Wright at Bryn Mawr when he taught history there in the early 1880s (fit justice for his double hardness of heart!). Wavering on what to do with the rest of my life, I had also been considering advertising and journalism, and to try out the latter I had spent the summer of 1959 writing obits and various other articles for the Quincy Patriot Ledger in Quincy, Massachusetts (just south of Boston), where one of my deskmates was an attractive, highly articulate young lady named Pauline Rubbelke, a rising Radcliffe senior who would later become--as Pauline Maier--a renowned specialist in early American history. Though we dated a few times, she was already engaged to be engaged to Charles Maier, the eminent Harvard historian whom I now count among my good friends, and like countless others I was deeply saddened to learn of Pauline's sudden death of lung cancer in August of 2013.

But that summer was the beginning and end of my mini-career in journalism. Since the Wilson application required me to say that I was at least considering an academic career, I did so, and when I was lucky enough to win a fellowship for graduate study in English, it seemed to signal--strongly-- that I should spend my life on literature.

For the Class of 1960 at Georgetown, graduation day fell on a Monday afternoon in early June. The Commencement Address was delivered by Carlos P. Romulo, the Philippine Ambassador, whose son Bobby was graduating with us and who later became Philippine Secretary of Foreign Affairs. Though I remember not a word of his father's address, I well remember something I learned in the midst of a boozy, boisterous party at a Washington hotel suite on the previous Saturday night.

In the midst of this mashup I fell into a quiet conversation with a classmate I had known since our freshman year--but largely on the surface. My first memory of him is a mental filmstrip. Pitching down the stairs at Ryan Hall, where I lived on the second floor and where we all took our meals in the ground floor cafeteria, John wore on his face what I can only describe as a shit-eating grin. It turned out to exemplify his persona. Slighting his courses, he chuckled a lot, drank heavily, and partied often with a few other party boys, as his clique were known. One night I spotted him stepping out in a black tux with a big red sash across his chest from upper left to lower right: the bar sinister of ancient heraldry, as if to flaunt his illegitimacy! Except for snickering once at the "shit" I put into the humor columns I was writing for the Hoya, GU's student paper, under the suave pseudonym of "George Townley," he seldom spoke to me.

But now and then, on the rare occasions when he did, I caught a glimpse of something deeper. When I once misidentified F. Scott Fitzgerald as the author of Eugene O'Neill's Ah Wilderness!, he not only corrected me but told me that Fitzgerald had written just one play called The Vegetable--surely a rare bit of theatrical trivia I had never met before and never since. And in the spring of our senior year, when I shared a room with him and two others during a weekend of Spiritual Retreat somewhere in Maryland, I sneaked a look at his notebook while he was out of the room. Crammed onto one page after another, its handwritten notes on Othello probed the jealousy of Shakespeare's doomed Moor with passionate, revelatory insight.

So beside the fact that he had also written the student show, a zany take on show biz itself (which he loved), I should probably not have been surprised by what John quietly told me in the midst of that graduation weekend party. Headed, he said, for the Yale Drama School in the fall, he planned to become a playwright. In retrospect, I link the memory of this moment with a line that John once quoted to me years later. In James Agee's Death in the Family, the narrator starts by remembering Knoxville, Tennessee, and "the time I lived there so successfully disguised to myself as a child." Talking with John that night, I began to realize that up to that point, he had been masquerading, disguised to me as a playboy. Now he was bent on being much more.

For the next ten years I heard nothing from or of him. But while watching the Dick Cavett show on TV one night in the spring of 1970, I suddenly saw him on the screen. Cavett was interviewing him about House of Blue Leaves, which had recently opened at the Truck and Warehouse Theater in Manhattan's East Village and had just won the Drama Critics Circle Award for Best American Play of the Year. Yes, you guessed it: I've been talking about John Guare.

The next day I went to the Hanover Post Office, dug his address out of a New York phone book, and wrote him a letter partly prompted by what he'd told a reporter for the New York Times about the characters in his play: while nobody ever said yes to their fantasies, he said, "somebody just said yes to mine." Bristling with ambivalence, caught between jealousy and admiration, I couldn't help needling him a little ("Do they call you St. John now? Pope John?") before seizing on what he had said. "You yourself," I wrote, "said yes to your fantasies." and kept on doing so for ten long years until you finally created this marvelous play.

Shortly afterwards, I saw the play, found it riveting, and then joined John for dinner. We've been good friends ever since, and since he's a voracious reader as well as a staggeringly prolific writer, I've never stopped learning from his own love of literature. When I told him a few years ago that I was working on a book about the literature prompted by the World War II, he steered me to Martha Gellhorn's A Stricken Field, a novel about the plight of Czechoslovakia that I ended up treating in Chapter 2.

Since Blue Leaves, of course, John has written a slew of stunningly original plays such as Lydie Breeze, for which he was called a "new American master." But he is probably best known for Six Degrees of Separation, which won an Obie Award, ran for nearly two years at Lincoln Center in the early 1990s, and has since been widely staged here and abroad. Lincoln Center also staged his Free Man of Color in 2010, which I must confess I found underwhelming. For all its satirical panache and the poignancy of its last act, this colossal contraption of a play reminded me of nothing so much as the gigantic linotype machine that ended up bankrupting Mark Twain. But when Nancy and I saw Nantucket Sleigh Ride at Lincoln Center in April of 2019, on the weekend of my 80th birthday, I loved every minute of it. As an octogenerian's madcap recycling of his life in the theater, it struck me as right up there with Verdi's Falstaff.

OK, now. Back to my life in 1960.

In the fall of that year I should have started my graduate work in English at Princeton. But having come down in September with both mononucleosis and Hepatitis B (a liver infection), I was hospitalized for a month of rest and had to miss the whole first semester of graduate courses. On getting out of the hospital and looking around for something to do beside getting a strong head start on course reading (which of course is what I should have done), I got a job selling Wearever Pots and Pans door to door to young single girls.

As Shakespeare's melancholy Jacques observes, one man in his time plays many parts, and since selling is not so far from teaching, perhaps it is just as well that I first took my turn at the former. From it I learned one thing above all others: there's nothing so chilling as a cold call.

I could sometimes get past the door by saying, "Mary, do you like nice things?" (as we were taught to say) and handing her a shiny little aluminum pan as a freebie. But standing in a strange living room with my big blue box of a sample case beside me, I often felt about as confident as Arthur Miller's Willy Loman on his lowest day. In two months I may have sold four Wearever sets, though that includes a whopper I unloaded on the very night JFK won the presidency. While the girl's whole family were going bonkers over early returns on the TV screen and rooting for him all the way, I somehow persuaded the girl herself to lay out a deposit on our biggest set of cookware before I went home to watch the remaining returns come in. I sometimes wonder if she still has those pots and pans.

I finally got to Princeton on a snowily wet day in February of 1961, settled into a ground-floor room on Dickinson Street (the

Graduate College rooms were all taken), and signed up for three courses that I'll say more about later. All graduate students were then fed in the Graduate College (the oldest residential college for graduate studies in the U.S.), and you had to wear a long black gown before sitting down to dinner each night at one of the long tables. But first the College Master intoned a stately Latin grace:

Pro cibo, omnipotens deus, atque potu, atque pro omnibus beneficiis tuis, gratias tibi agimus. Amen

For food, almighty God, and drink, and for all your benefits, we give thanks. Amen

On the rare occasions when somebody brought a female guest into the dining hall (she too had to be black-gowned for the purpose), the master's grace would include "atque puellis""--"and for the girls"--usually to murmurs of pleasure and/or ripples of applause.

Latin also came in handy for other purposes. One day when I had left my 1950 Chevy illegally or at least improperly parked outside the Graduate College, I saw the master about to give me a ticket. But just in time I said "Peccavi" (I have sinned), and he let me off.

When Andrew Fleming West became the first Dean of the Princeton Graduate College in 1900, he envisioned it as a forum for interdisciplinary conversation. At dinner each night, he imagined, budding physicists would talk with budding historians, philosophers, and literary scholars. But on my first night in that dining hall, I had a rude awakening. Shortly after I sat down with what turned out to be a table of physicists, I was told that the English grad students were all to be found "down there" at another table, which is where I sat for the rest of the term. So much for West's vision. But in starting out to study literature professionally, especially after missing one semester, I knew I had to give it my undivided attention. Only later would I link it to other fields such as history and visual art.

Soon after joining the English grad students at their special table, I started sipping Scotch before dinner with another English grad student named Jim Yoch, who had snagged a cozy, wood-panelled room at the College with its own fireplace. We were often joined by two other men--a classics grad student named Minor and an undergraduate named Clint. Though all thoroughly congenial, they would occasionally burst into giggles that mystified me until I discovered the cause after dimly suspecting it. One night Minor came to my room on Dickinson Street and told me what he felt that he had to tell me because he and Jim and Clint knew I was straight: they were all gay.

I have since come to know many gay men and count a few among my closest friends. But I had never before known any gays, and had grown up thinking they were all freaks or what we then called "fruits." I had known just one young man who had closeted himself so well that I didn't see the light until years afterward. When I was about 14, Paul's family moved into our Jamaica Plain neighborhood, and I soon found that he was interestingly different from the other kids Tom and I knew. In a word, he made better conversation, and I came to enjoy his company as much as he enjoyed mine. Since he too went to BC High and also seemed to share my nascent interest in girls, we often got together with two or more of them--most memorably when, before getting my driver's license, I drove the four of us around our neighborhood block in my mother's convertible and dented the right front door while grazing a driveway post on the way back in. (My parents were then off in Florida for a week, and I used my golf-caddying money to get it fixed before they returned.) A few years after we went our separate ways to college, Paul married a woman, and once in the late 1960s Nancy and I spent with the two a boozy night which, to Nancy's amusement but also the acute discomfort of Paul's wife, included a strip show in Boston's "combat zone."

Sometime in the 1970s, however, Paul finally came out and started his own gay bar. Though I had lost track of him by then, I later learned that sometime in the 80s he succumbed to AIDS.

So far as I can recall, the grad students of 1961 included just two black men--one an American studying musicology, and the other an Oxford-educated classicist from Ghana. With the regal bearing of an African prince, Alex Kwapong was tall, impeccably well-spoken, and about ten years older than the rest of us. He was also slightly condescending. After dinner he would sometimes stop by the English grad table, lean over it with a smile, and a sing a few bars of a commercial jingle such as the one for Alka-Seltzer: "Ploo plop fizz fizz / O what a relief it is."

Years later I heard a story about him from Conor Cruise O'Brien, an Irish historian and politician who spent several terms at Dartmouth in mid 1980s. (Juicy stories about O'Brien himself are available on request.) In the early sixties, I learned, when O'Brien was Vice Chancellor of the University of Ghana, Alex was his deputy (and he later became Vice Chancellor himself from 1966 to 1975.) One day they were visited by a band of young Marxists bent on radicalizing the whole university. O'Brien's response was fair but also firm and clear. If one of the group wanted to give a speech, he said, he would give them a hall for the purpose and even advertise it to the students, But he would not allow a mass rally on university grounds incited by a "band of ruffians." Incensed by this phrase, the leader of the band turned hotly to Alex, his fellow Ghanian, from whom he clearly expected a more sympathetic response. "Ruffians!" he shouted. "He called us ruffians!" To which Alex replied in his impeccably British accent,"It's a perfectly good word. You'll find it in Shakespeare."

Turning back to those I knew well at Princeton, Jim Yoch remained a good friend for years, ended up happily married to a lovely woman named Nancy, and managed to combine the teaching of Shakespeare at the University of Oklahoma with a thriving practice as a garden designer in this country and abroad. (His books include one on his aunt, Landscaping the American Dream: The Gardens and Film Sets of Florence Yoch : 1890-1972.) Apart from Jim, the English grad students I got to know were all straight as well as white and male. With the single exception of one woman who came for just a term (and whose name now escapes me), the professors too were all white and male, and in the spring of 1961, they could hardly foresee what waves would be breaking on the shores of academe by the end of the decade. They knew nothing of feminist criticism, Orientalism, post-colonial ideology, African-American literature, or deconstruction. Stuck in Princton amber, they mostly taught literature in its historical contexts, one period after another.

A perfect example was the second (spring semester) half of the Eighteenth-Century Literature seminar that I took under Louis Landa, who treated every work of poetry, fiction, and drama in the course as a web of threads leading to other texts: not just its sources (and there were always sources) but the whole literary-historical context surrounding it. In the previous decade of the 1950s, this kind of spidering had been attacked by the New Critics, who argued that a work of literature, especially a poem--could and should be read, studied, and interpreted all by itself, without reference to anything outside it, not even the biography or intentions (who knew what they were anyway?) of the poet who wrote it. What mattered, they claimed, was not the poet or the contextual web that might be found woven around it but rather the imagery of the poem itself and its own internal network of threads running between one image and another.

Professor Landa was not a New Critic. On the contrary, he considered that kind of criticism just a game for undergraduates to play. Graduate students, he believed, should learn to read works literature through the lens of literary history, or within its great webwork, for only then could one say or write anything worthwhile about a poem, novel, or play.

Since we were each assigned a long paper at the end of the course, I sought his advice, and for some reason he suggested that I write on "the picturesque." Though I'd never heard of it before, the picturesque turned out to be a web of its own threading pictures to landscape, garden design, and poetry, so it ended up leading me later into the interdisciplinary study of literature and art--one of my chief pursuits. But at the time, as I was told by an older grad student, the name of the game was scavenging: searching the period for just about anything I could find on the topic assigned. Though I soon learned that the great big bag of "the picturesque" included Payne Knight's "The Landscape: A Didactic Poem. In Three Books. Addressed to Sir Uvedale Price, Esq." (1794), my job was not to investigate this poem, which I think I can safely say--after slogging through about a dozen lines of it-- hardly makes the cut as a work of literature. No. My job was to mine the turgid prose of Uvedale Price, who became the "master theorist of the picturesque," and then ransack the periodicals and pamphlets of the 1790s to see what else was being written about the topic. "The more obscure and fugitive your sources," I was told (again by an older grad student), the better.

So I scavenged for a slew of sources, wove them together, and somehow managed to earn a grade of Excellent. But since my prose was then strongly infected by the hyper-kinetic style of Time magazine, which led me to lean heavily on verbs such as carped, sneered, and pounced, Professor Landa noted that he had sometimes felt the paper turning convulsive in his hands.

Though some of my other professors were somewhat more ready and willing to savor the pleasures of literature, there was just one major exception to the kind of literary criticism exemplified by Landa's approach. He was Richard Blackmur, the poet and critic I mentioned above in the previous chapter. Blackmur was sui generis, a man whose incandescent mind could light up any work of literature he cared to mention. He was largely self-educated. Born in 1904, son of a boarding house in Cambridge, Massachusetts run by his mother for Harvard boys, he was kicked out of high school in his junior year for quarrelling with the headmaster. Living thereafter on the edge of poverty, he made his name so well as a critic and editor of the "little" magazine Hound & Horn that he had been invited to join the Princeton English faculty in the fall of 1940. At the time, a friend told him that his joining of the English Department would mean the death of its literary historicism. "As if anything could kill it," he told some of us later.

In his own way, however, he did his best to "blow up the neighborhood with his chemistry set," as Russell Fraser wrote in a wonderful piece about him now readily available online ("Richard Blackmur: America's Best Critic," Virginia Quarterly Review, Autumn 1981). He taught with no syllabus, no pre-ordained list of assignments. For his graduate seminar on Poetics, which I audited in the fall semester of 1962, he would simply improvise his agenda from one week to the next--and sometimes even ask us what we would like to hear him talk about next. After I ventured to propose "Samuel Johnson" at the end of one session, he turned up for the next one with a sheaf of linen paper (imported from Italy, I was told) on which he had written--in an exquisitely fine hand--a magisterially compact account of Johnson's literary criticism. It was couched in the signature style of the Great Cam himself (suspended predication, tidy parallelism, deft antitheses), which Blackmur felt bound to adopt (he said) when writing about Johnson. Best of all, or worst of all for those who found him too esoteric (as some did), he was given to Sybilline musings such as "Dante and Shakespeare: strange apparitions of possibility." He was something of an apparition himself. Troubled with bad circulation, as he told me one day after class while we stood by a crosswalk on Nassau Street, he died in 1965 at the hardly advanced age of 61.

Strangely enough, I remember with particular fondness the course on Old English that I took in that first spring semester of 1961. Taught by a spirited, congenial guy named Jack Campbell (we called him Jolly Jack), it opened my eyes and ears to the haunting beauty of the Old English tongue. Once you dug into the roots of English, I learned, and scraped the accumulated mud off what you found there, you could finger thousand-year-old nuggets such as this one from "The Traveller's Song":

eal scaceth

leoht and lif somod

light and life together

disappear all at once

Whenever I hear of a sudden death, these two simple lines on the evanescence of life run through my mind.

From short Anglo-Saxon poems we moved on to Beowulf, the epic probably best known for neatly bookending the history of English lit from Beowulf to Virginia Woolf. For my final oral exam in the course, I memorized the passage (and I can still recite some of it) in which the titular hero bids farewell to Hrothgar, King of the Half-Danes, whose people he has relieved from two murderous monsters--Grendel and Grendel's "dam" or mother--by killing them both. As the two men hug and kiss each other goodbye, they hope to meet again but feel in their bones and burning blood that they will never do so. Years later, while revisiting Beowulf for Hospitality and Treachery in Western Literature, I not only used this poignant passage to exemplify the parting of a royal host and his guest, but also discovered that when Beowulf tracks the mother of Grendal to her lair at the bottom of a lake, he is called, by a grim and wonderful irony, the monster's gist--her guest.

During my next two semesters at Princeton in the fall of 1961 and the spring of 1962, I took a year-long seminar on Shakespeare from Professor Gerald Eades Bentley, a precise and exacting Midwesterner who had made his academic name years before with a history of English Renaissance drama: The Jacobean and Caroline Stage (1941). Meeting us once a week for two hours, he filled the first half of each session with a carefully prepared and kinetically delivered lecture (though sitting, he would sometimes pivot his shoulders to emphasize a point.) After his lecture on Midsummer Night's Dream, I learned something juicy from an Australian classmate named Gary Scrimgeour, who was some years older than the rest of us and considerably better read. (Though he never got around to following a normal academic track, Gary went on to publish a fascinating novel called A Woman of Her Times in 1982). As he and I left the seminar room after Bentley's lecture on MND, Gary told me, "He got all of that out of Harley Granville-Barker." I don't think all the lecture had been swiped from Granville-Barker's "Preface to Midsummer Night's Dream" (from his much-published Prefaces to Shakespeare), but my own reading of that preface led me to see exactly where at least some of the lecture originated. And I suddenly realized that for all the rules against plagiarism on college campuses, rules that require the writer to cite the source of every line quoted or paraphrased from someone else, there are no rules against a professor's ventriloquizing of any source without citing it--so long as it's done in a lecture.

For the entire year long course, Bentley assigned just one paper of about twenty double-spaced pages that was due in mid-February with absolutely no chance of an extended deadline. After deciding to write on Shakespeare's use of Ovid in the early plays, a topic he suggested and that sounded fairly manageable, I started thinking about it sometime in the fall but put off working on it until early January--a month before its due date--when I rather casually got started. In later years, when I gave myself plenty of time to meet deadlines, I would normally finish writing well before they landed. But in this year, when I could have taken months to write the Shakespeare paper, I put off writing nearly all of it until the night before it was due.

Like just about every other student in the class, I pulled an all-nighter, which makes absolutely no sense but was nonetheless the kind of thing we often did. And somewhere in the dark wee hours of the morning, as I struggled to explain on my clacking Royal typewriter how a young English playwright re-purposed for the stage the words of an ancient Latin poet, I had a minor hallucination.

From the small Norelco radio that I had set going to keep me awake through the night, I heard the name of my father. As I learned only then, he was in the news because he had just performed an operation on Rose Kennedy, mother of the sitting President JFK. (Reporting it as a hernia repair though it was actually something more intimate that Rose did not want publicized, he charged her $500.) Maybe that bit of news helped me finish hunt-and-pecking my way through the paper, because it earned a respectable grade.

In the fall of 1962, I passed my general exams for the doctorate at Princeton after just three semesters of course work. If you think that means I must have been a Wunderkind, you would be dead wrong. Woefully under-prepared, I nearly flunked it, and passing it was mainly the product of luck.

Without such luck, which has many times saved me from various scrapes and disasters, my life might have ended one spring afternoon in the mid-fifties, when I was about sixteen. When a friend and I rented a couple of horses from the Canton Equestrian Center south of Boston, I mounted my coal-black stallion without a care in the world for what I've since been told is the first rule of riding: keep the reins tight and make the horse know who's boss. Though I had doubtless heard something about this rule at North Woods summer camp, where I first learned the rudiments of riding, I blithely ignored or forgot it on that afternoon--to my peril.

Since my stallion had probably spent nearly all of the winter boxed up in his stable, he was just as probably itching to stretch his legs. So as soon as the stony bridle path turned long and straight, he took off at what was at least a gallop if not a full run. Then he suddenly dropped his head, dug in his front hooves, and flung up his rear end. I was thus front-somersaulted over his head and thrown down flat on my back on the stony path right before the horse. Though unhelmeted (at age 16, who needs a helmet?), my head was perfectly intact, and though I felt a bit shaken, I had broken no bones nor even suffered any bruises.

So what did I do next? The second rule of riding, I've been told, is that whenever you fall or get thrown off a horse, you should get right back on again so as to forestall the paralyzing trauma that might otherwise keep you from horseback riding ever again. While unknowingly heeding this Rule #2, I still gave no thought to Rule #1. Somehow imagining that the horse would now be more considerate, I re-mounted, gave him his head, and underwent a second somersault that left me once again flat on my back on the ground--and also once again miraculously unhurt. But this time was different. What made it so was something I'll never forget: the gleam of fury in the eyes of that horse as he looked down at me from on high. So I walked him back to the stables and got another horse.

In 1995, about forty years after this episode, Christopher Reeves--aka Superman, and a far better rider than I ever was--was paralyzed from the neck down after falling from a horse during a cross-country event, and Wikipedia lists a slew of others who have been killed or badly injured while horseback riding. Whenever I recall my own sequence of somersaults, I am freshly amazed at my own folly in doubly tempting fate and freshly aghast at what might so easily have happened to me.

At Princeton in the fall of 1962, I was hardly better equipped to take the general exams for the doctorate than I had been to manage my headstrong horse. In that era we had no reading lists to guide us. Officially, at least, we were responsible for all of English and American literature from Beowulf to Virginia Woolf and beyond. At my parents' house in Milton I had spent the summer cramming with mimeographed purple "poop sheets" worked up by older grad students: potted answers to questions asked in previous years' exams. But I knew I was skating on very thin ice, and I nearly fell through it.

Given what I had learned from my courses, I did very well on a question about Beowulf and reasonably well with questions about Jonathan Swift and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. But I had nothing to say about Milton's Paradise Lost, which of course I should have studied closely, and I had almost nothing to say about American literature, which I knew only from a single undergraduate course. So when I walked into the oral exam after submitting the written one, I was hardly brimming with confidence.

I can scarcely remember the questions. But to several I had to plead ignorance, and for some of the others I had little more. What saved me in part, I suspect, was my previous work. Since I had earned grades of Excellent or Very Good in all my courses, the professors might have felt that they had to stop short of the guillotine. So I squeaked through with a grade of "Passing" and a warning that I would be asked about Milton on the final oral for the doctorate. I have long since realized that "mastering" the full range of English and American literature takes a lifetime of study, teaching, and writing--if it ever gets mastered at all.

Next came my dissertation. Having taken English Romantic poetry with Professor Carlos Baker in the spring of 1961 and written a paper on Wordsworth's theory of imagination as laid out in his prefaces and essays, I decided to write on the whole topic of imagination as not only described in his prose but exemplified by his poetry. Baker took me on while pursuing a quite different project of his own. Though his first book had examined the poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley, he was then working on his much-admired biography of Ernest Hemingway, which would come out in 1969 (eight years after Hemingway put a rifle to his head). But he kindly agreed to supervise my work on Wordsworth, and proved to be extraordinarily prompt and generous with his advice. Whenever I hear tales of doctoral students slighted by their advisers, who (to be fair) sometimes have to oversee half a dozen or more projects at one time, I marvel at what I got from Baker in the summer of 1963, when I was his one and only advisee. By September I had finished all but some footnotes and the bibliography--just in time to start my teaching career as an Instructor in English at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

With all my worldly goods (clothes, books, assorted pots and pans) packed into the pea-green 1950 Chevy that I had bought for just $100 in the spring of 1960, I reached Charlottesville for the first time on a warm sunny day in September 1963. After hiring a young Black man to help me unload my stuff, I drove to a local fast-food eatery to buy us lunch--only to learn that he would not be allowed in. So I bought us sandwiches to go. A few weeks later, I signed on for a sit-in at the same restaurant, but I must confess I was relieved when for some reason it was cancelled at the last minute. My only real brush with segregationist sentiment came in December of 1964, soon after the local Daily Progress published a letter of mine about the Nobel Peace Prize just awarded to Martin Luther King Jr. For strongly defending King's right to the award against the rather grudging stance of an editorial, I was scowled at by a few of my colleagues.

Most of them, however, proved quite congenial, and a few became lifelong friends, as I shall shortly explain. But first a word about working conditions. At UVA in the fall of 1963, the English Department was not just chaired but ruled by Fredson Bowers, a brisk and balding autocrat who had made his name with books on Shakespeare and Elizabethan drama but now specialized in bibliography--the study of printed texts and all their peculiarities. As a mere Instructor, I was never invited to meetings of the English Department faculty, but once a week, after all of its members including me had lunched at a local restaurant, Fredson would announce a pyramidal sequence of meetings: first, Full Professors plus Associates and Assistants; second, Full Professors and Associates; third, Full Professors. But all major decisions, I suspected, would be made a final meeting of Fredson with himself at the very top of the pyramid.

The teaching load was heavy. Though I had just two courses to prepare, one on English comp and the other on a survey of English and American literature, I taught them in two sections each, with 20 students for each section of English comp and 35 each for the survey. So besides preparing classes on composition and literary works that I had sometimes never read before, I had to grade papers written by a total of over one hundred students, including 40 a week from the comp students and 70 x 2 from the survey sections--one short paper at mid-semester, and a longer one near the end. In other words, I had to grade several hundred papers that first semester.

Throughout my teaching career, which lasted 41 years, I have always found paper-grading the most tedious part of the job. Now and then, of course, I have read student papers so well-written that all they needed was the letter A. But those were far outnumbered by papers needing far more. To grade such papers conscientiously, to identify their strengths and weaknesses clearly, was almost always a task I dreaded, and was immensely glad to put behind me when I at last retired.

And in spite of the workload, I found time for booze and parties, which were readily available then. (So far as I can tell, younger members of the professoriate now seem much more sober and far less frivolous than we were.) But on one memorable occasion, I made the nearly disastrous mistake of attending a party on the Sunday night before I was scheduled to teach three classes on Monday--including one on a Shakespeare play that I had somehow never got around to reading before, even during that year-long course with Bentley. (Academic craziness: he had us reading so many secondary sources for each week's class that I sometimes skipped the play assigned for it.)

Let me first give you a short history of my drinking life. Though never an alcoholic and now a quite moderate tippler, I have had my drunken bouts, and the worst of all came in the spring of my freshman year at Georgetown, when--during the Spring Weekend Fling or whatever it was called--I joined a cocktail party at Washington's Shoreham Hotel along with a onetime high school girlfriend who had obligingly flown down from Boston to be my date.

Since I was running for Sophomore Class President at the time (my one and only abortive fling at student politics: I came in dead last), I should have been schmoozing with every other classmate I saw. Instead, sheer nervousness drove me to a little table that happened to be momentarily abandoned--except for three or four stemmed martini glasses that I saw were still half-filled. In about sixty seconds I downed them all. A few minutes later, when a friend suggested we move on to a steak dinner, it sounded like a perfect idea, but I never made it to the restaurant. Instead I was driven back to Ryan Hall, hauled up the stairs to my room, and deposited fully clothed on my bed, where I woke around three in the morning with what felt like a railroad spike driven right through my head.

I wish I could say that this episode cured me of drinking--or at least heavy drinking--but it did not. Six years later, in the fall of 1963 at UVA, I was still ready to party hard, and ready too now for bourbon (a Southern favorite, of course) as well as for that demon called gin. So I not only accepted the invitation to a post-prandial party on Sunday night but steadily drank my way into the wee hours of the following morn. After driving back to my ground-floor UVA apartment on Mimosa Drive (I was just barely able to do that), I set my alarm for 5:00 AM, flopped into bed, and fell asleep.

Duly awakened at 5:00 AM, I began reading for the very first time the play I was scheduled to teach in two classes later that day: Shakespeare's Henry IV Part I, which begins with the words of the king:

So shaken as we are, so pale with care.. . .

I couldn't believe it. Exactly how I felt.

After halfway digesting the play, I decided to open the class by frankly confessing that I was suffering from a major hangover and then segue into talking about the political hangover caused by Henry's deposition of Richard II, his predecessor, and the resulting turmoil of the kingdom. Anything to get me through my three classes: English comp at 10, lit survey at noon, and again at 2:00. But unlike the first two classes, which took 50 minutes, the third was a killer at 75. All day long, I told myself that if I could stagger through this one day, I could probably survive anything that might come thereafter, and to my amazement I did. My reward was a heady ride in a private plane piloted by a colleague named Jim Colvert, who had earlier kindly offered to take me up on the afternoon of that very day.

The first two colleagues I got to know well were a fascinating pair of gays who were very good friends of each other though not romantically attached. One was a tall Kentuckian named Fred Bornhauser, the other a short, trim gnome from Gary, Indiana named Donald Mull. A Rhodes scholar who at 37 was still working (or shirking?) on his Cornell dissertation, Fred was the most cultivated man I ever met, breathtakingly well-versed in art and music as well as literature. He shared with Don his particular passion for opera, and together they introduced me to Wagner, especially the four operas of the Ring cycle, whose fiendishly complicated story Don had thoroughly mastered.

We drank together often, especially at Fred's apartment, which was just a few steps from mine on the ground floor of the next building over. Uninvited, I often just dropped in him. He would let me through the door just about anytime I knocked at it, and as soon as we were joined by several other drop-ins, as we often were (especially by Don), the party was on. If it went on past 6:00 PM, Fred would often conjure up a meal for us in his tiny kitchen, and when the results were duly tasted and warmly praised, he would invariably say, "Just a simple supper: so happy you could share it with me."

But Fred never formally entertained anyone at his own place. During his first year at UVA, I later learned, his charm and wit got him invited to so many fancy dinners that he was finally urged (by a friend named Ruth) to start reciprocating them. To which he replied, "I like to entertain people in their own houses."

Somewhere in my second year of teaching at UVA, Fred actually finished writing his dissertation on the early poems of John Crowe Ransom ("Disowned Progeny," he called it), and since getting from Charlottesville to Ithaca was exceptionally complicated by any other means, he was flown there-- by our colleague Jim Colvert. The Cornell professors of English were so happy to see his dissertation finished at last that they asked him just one thing: what question would he like them to pose? Whereupon he told them, "How on earth did you get here today?"

Besides going to parties that year I looked around for some female company. Since there were almost no women of any kind on the faculty then and since the few women graduate students I met seem to have been already tied up with other grad students, I decided to call up a young woman named Diana, aka Dee, whom I had come to know during my senior year at Georgetown and who was now living and working in DC, about a hundred miles northeast of Charlottesville. Some might find that too far to go for an evening date. When William Faulkner was writer in residence at UVA in 1961, some years after winning the Nobel Prize for literature, he was invited to join a legendary dinner at the White House hosted by Jack and Jacqueline Kennedy to honor a whole galaxy of cultural stars. But Faulker declined. DC, he said, was "a long way to go just to eat."

Since it didn't seem a long way to me, I called Dee in Washington to ask her out. As the only child of a retired American admiral, she had lived in a number of places including Paris and Switzerland, but her family's summer house in Murray Bay, northeast of Quebec City in Canada, was the only permanent home she knew. She had entered the Georgetown School of Foreign Service (SFS) in 1956, the same year I started at the College, but we did not meet until the fall of senior year. Smart, vivacious, always ready to laugh, and just a teensy bit Rubensian (my roommate called her "hippy"), Dee not only zipped around in a bright red Triumph-3 convertible but also had her own apartment up on nearby Foxhall Road, where she gave the most cosmopolitan cocktail parties I had ever attended. I marvelled at the way she would introduce her Latin American guests to her various European guests--all fellow students from the GU SFS--without mispronouncing a single name.

During a flirtation that lasted a few months, I thoroughly enjoyed her company, and though we had stopped dating by the spring of 1960, she remained a good friend. The friendship survived both my marriage to Nancy (whom she came to like very much) and hers to the late David Nicholson, with whom she founded a legendary Montreal salon known as Wednesday night. Every single Wednesday night without fail from its launch in 1982 to 2018, when David died, he and Dee gathered in their commodious Rosemont house a company of Montreal notables (academics, artists, politicians, writers) to discuss the major issues of the day. And as I write these words, Dee is still holding the salon every week in her large new apartment.

Now back to the fall of 1963. When I phoned Dee for a date, she told me that she was moving to Montreal to work on planning the 1967 International Exhibition (Expo67), and invited me to her own farewell cocktail party. When I asked if she would like to have dinner with me afterwards, she said she was otherwise engaged, but also suggested that I make a date with someone else and bring her along.

Meanwhile, from a sociable young colleague named Conrad Warlick I had already heard about a young woman he had come to know while they had both been earning Masters degrees in English at UVA. Though she had gone on to teach for a couple of years at two small women's colleges in rural Virginia, she was now working in the Admissions Office of Mount Vernon Junior College on Foxhall Road. And though she and Conrad had remained good friends, his Southern gentlemanly tastes ran to girls conventionally decorous, so he was not drawn to her himself.

From his description Nancy sounded somewhat unconventional, a bit indecorous, and maybe even a little wild. (Years later, I learned, one highly conventional lady said of her, "If Nancy joins this group, all hell will break loose.") To me she sounded enticingly vivacious, so I invited Conrad to supper at my place (I could manage a simple one), and once we finished our meal, I asked him to call her, introduce me, and hand me the phone. Luckily enough, as I later learned, she liked the sound of my base voice, so she readily agreed to be my date for the evening of Dee's party.

On the night I picked her up, she'd been rooming in a swanky Georgetown townhouse in return for occasionally minding its pampered kids. The lady of the house, named Jean, was not only rich but laughably pretentious, which played a key part in my first conversation with Nancy. The only other thing you need to know is that at this long embalmed era in the history of fashion, no well-bred and well-dressed young lady would step out for the night with bare hands. They had to be sheathed in white gloves.

When Nancy opened the front door for me, I was dazzled. As William Wordsworth wrote of Mary Hutchinson, the woman he married way back in 1802,

She was a phantom of delight when she first gleamed upon my sight.

And to judge from the pictures of Mary that I've found online, Nancy was (and is) far better looking. Better still, feeling bound to explain why she was bare-handed, she told me that she had just asked Jean if Jean had seen her white gloves anywhere near the door. No, Jean had said, "I've seen only my Dior white gloves." Thus cracking both of us up in thirty seconds flat, Nancy perfectly launched our first evening together, which in turn led to a marriage that has now lasted sixty years.

She said yes on New Year's Eve, just six weeks after our first date, and we got officially engaged in March. On June 27, a couple of weeks after I passed my final oral for the PhD at Princeton (after duly fielding a softball question on Milton's Paradise Lost), we were married in Lynchburg, Virginia. At the rehearsal dinner on the night before--with dancing too at the James River Club in Scottsville, a few miles south of Charlottesville--I couldn't resist toasting Nancy with a line stolen from Shakespeare:

Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale her infinite variety.

Of course the Egyptian Queen who is thus described by a friend of Marc Antony in Antony and Cleopatra scarcely lived long enough to make good on this claim. Unlike her, Nancy remains wholly unwithered and infinitely various after sixty years.

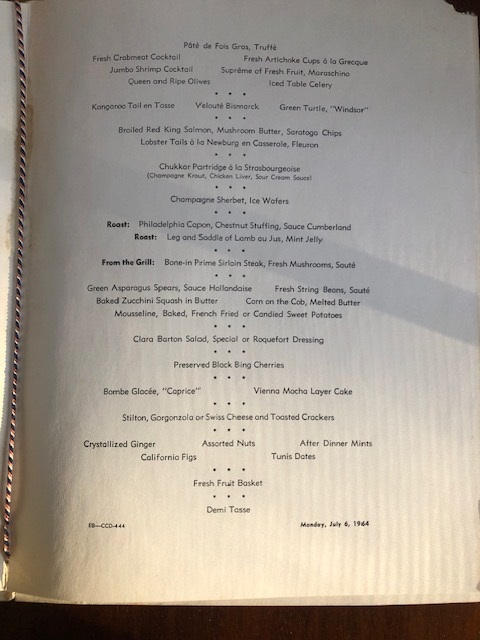

Thanks to the great generosity of my father, we spent most of that summer driving though Europe in a rented Sunbeam Imp just big enough to hold the two of us. But first we crossed the Atlantic in the old-fashioned way, by ship. During five langorous days on the SS United States (now rusting away, I'm told, at a dock on the South Philadelphia waterfront), the hardest thing we had to do was work up an appetite for the next meal. Lunch alone would run to nine courses, and since they were all included in our Cabin Class fare, we felt bound--or rather I felt bound--to sample all of them. Most Rabelaisian of all was the gala dinner served on July 6, 1964 and here preserved in the amber of a menu that Nancy has just retrieved from our family archives:

I wish I could say that like the undying taste of Proust's tea-tinctured madeleine, the taste of the kangaroo tail has lingered unforgettably on the palate of my memory. But I can't.

Disembarking at L'Havre after a brief stop at Southampton, we trained to the Gare St, Lazare in Paris and checked into the Hotel Nancy (I kid you not) on the Left Bank Rue Bonaparte. Now long gone, the Nancy was a little snuggery run by Armand Janou (I still remember his name!), where for 25 francs a night --five bucks!--we had a double room with bidet (bathroom down the hall) and petit dejeuner delivered to us each morning. And French doors overlooking a tiny balcony from which I now and then addressed bemused passersby in my rudimentary French, sotto voce: "Bonjour, mes chers amis!"

Speaking of five bucks, our vade mecum for this trip was the first edition of Arthur Frommer's Europe on Five Dollars a Day, which had just been published. Since this book promised to guide us through Europe on five bucks a day per person, I reckoned that we two could afford $15 a day, which gave us five whole extra bucks to play with. And amazingly enough, it worked. With Frommer's help, we found our way not only to the Hotel Nancy but also to Left Bank restaurants such as the Beaux Arts, where 7 francs ($1.40) would buy you steak and pomme frites, and 20 francs ($4.00) dinner for two including a petit carafe of vin rouge.

One night there we got chatting with a couple of young American men who had flown in from New York, where they worked in the kitchen of the august temple of haute cuisine known as the Four Seasons. Duly impressed, I quizzed them about how to prepare for dinner there if we could ever afford to do so (eat lightly that day, they said), which in fact we never did. But in any case, after drinking several glasses of red wine after dinner, we were appalled to learn that we would have to pay 3 francs--60 cents!--for each of them.

Since we all felt a bit woozy as we got up from the table, one of the guys suggested we try a bowl of French onion soup at Les Halles, the great open air market then sprawled out in the center of Paris, from which it has long since decamped. As we taxied along through the night and rounded the Eiffel Tower on route, I drank up the lights of the city as if they were flutes of champagne. But by the time we reached Les Halles, Nancy needed my help in getting to a restaurant. While propping her up as we wobbled across the cobbled pavement in the dark, I was suddenly struck in the right ear and thrown to the pavement. I'd been caught by the edge of a little white van driven by a man who turned around, looked at me, and simply shrugged when I brandished my fist and called out "bâtarde!" in my bastard French. Bloodied but unbowed, I pressed on with Nancy and our nonce friends to the solaces of onion soup.

During that week we tried to tag all the requisite bases for first time visitors to Paris: Notre Dame, Sacre Coeur in Montmartre (Picasso's old haunt), the Louvre, the Hotel des Invalides with its huge purple block of porphyry commemorating Napoleon, and even the Lido, where for 35 francs or $7.00, meaning a just barely tolerable $14.00 for two, you could buy a drink at the bar and stand there among the packed crowd nursing it for an hour or two and thus get to savor the pirouettes of the lovely, bare-breasted ladies (Nancy didn't mind) whose charms would otherwise have been unaffordable.

From the rest of our trip, which took us from France to Italy, back through Switzerland, and finally to England and Scotland, I could revive many episodes but I will single out just a few. 1. At the Théâtre de la Gaïté in Montparnasse we saw Marcel Marceau, the world's greatest mime, practice what he called "the art of silence" by staging a self-contradiction: with face frozen into a smile he could not break, every other part of his body voiced its anguish. 2. Somewhere along the road in southern France one sunny afternoon I bought a pair of fresh, succulent yellow peaches and, standing by the roadside, grinningly devoured one as its juices rolled down both my chin and my neck. 3. In the Piazza di Spagna of Rome, just a few steps from the apartment (now a small museum) where the terminally tubercular John Keats breathed his last on 23 February 1821, we met a middle-aged man standing by a crumbling fountain that was then bone dry. "Are you Americans?" he asked us. We said yes. "I'm American too. And I'll tell you this: I've been all over Europe, and it's all crummy." 4. Lunching at a Roman trattoria one day, we hear a nearby young couple speaking British-accented English and soon learn that they too have just been married. Thus began our lifelong friendship with Jeremy Roberts, who became a distinguished judge, and his wife Sally. During our many trips to England they have treated us with exceptional hospitality. 5. In Chichester, England, we saw the 57-year-old Laurence Olivier impersonate Shakespeare's Othello as a minstrel in blackface--the layers of makeup reportedly took him three hours to don--with an accent so velvety thick it could be cut with a knife. (Though he poured all of his theatrical energy into the role, it's safe to say that in England at least, Othello was never again played by a white actor.) 6. Landing at Dover after the ferry ride from Calais, Nancy was so starved for the English language (which for weeks she'd barely heard from anyone but me) that she fell upon a customs officer and told him half the story of her life. 7. And in Scotland we caught the Edinburgh Festival including its "fringe," where Alan Bennet and the three other stars of what later became Beyond the Fringe on Broadway celebrated the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare's birth by gleefully riffing on his history plays: "Get thee to Salisbury, Worcester." Answer: "Get thee to Worcester, Salisbury." Answer: "O, saucy Worcester!!"

Altogether a great trip. Even though we fought like tomcats every time we got lost in the narrow, often one-way and sometimes dead-ended streets of a new city (Nancy would navigate from a page of the Guide Michelin while I disputed her directions), I can't think of any better way in which we could have launched our marriage. But I should add that on the flight home (no fancy ship this time), I spent what I thought was our last five bucks on a couple of gin and tonics. We would have landed penniless if Nancy hadn't salted away somewhere--fortunately without telling me--her last fifty.

On returning to the University of Virginia for my second year as an Instructor in English, I soon discovered that Fredson Bowers had no plans to keep me beyond the third and final year of my contract. (I had by then published nothing, and he must have known that I had barely passed my general exams at Princeton, which made me cannon fodder.) Fortunately, college teaching jobs were plentiful in those days (unlike now), so I decided to put myself back on the market. And since Professor Baker was not only a Dartmouth graduate but also kept in touch with its English faculty, he recommended me to its English Department (yes indeed, the old boy network at work).

Soon after, I was invited for an interview at the prime job-hunting ground for all young literary scholars: the Annual Convention of the Modern Language Association (MLA), which met that year in New York just after Christmas of 1964.

At Dartmouth now (and probably also at just about all other colleges and universities), getting a job is an obstacle course. After first being interviewed at a professional meeting such as the MLA Convention, a candidate who clears that hurdle is invited to give a sample lecture on campus to the whole department, and only then is he or she voted on by all of its members or at least all of its tenured ones. But way back in the good or bad old days of 1964, things were much simpler. After fifteen minutes of an easy and most enjoyable chat with three members of the Dartmouth English Department--one of whom, Jim Cox, I liked immediately--I was offered an Assistant Professorship at $8500--more than $1000 over what I was then getting at UVA. I accepted at once, and early the next September, towing a small U-Haul trailer behind us, Nancy and I drove for the first time to Hanover, New Hampshire, the home of Dartmouth College.