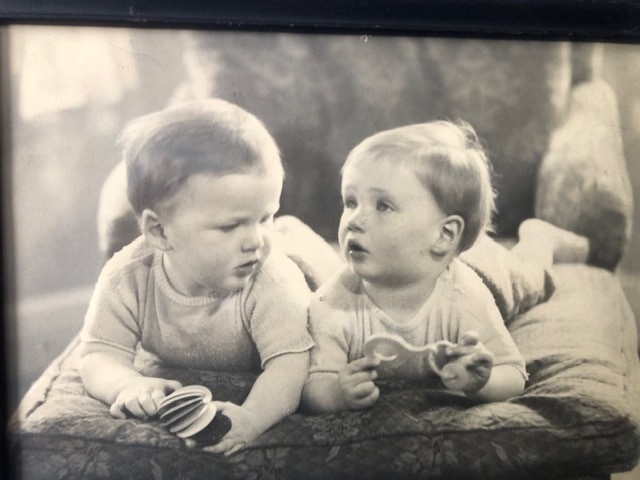

The author at left, with fraternal twin brother Tom, circa 1940.

Where do we find ourselves? In a series of which we do not know the extremes, and believe that it has none. We wake and find ourselves on a stair; there are stairs below us, which we seem to have ascended; there are stairs above us, many a one, which go upward and out of sight. But the Genius which, according to the old belief, stands at the door by which we enter, and gives us the lethe to drink, that we may tell no tales, mixed the cup too strongly, and we cannot shake off the lethargy now at noonday.

--Ralph Waldo Emerson, "Experience"

But who shall parcel out

His intellect, by geometric rules,

Split, like a province, into round and square?

Who knows the individual hour in which

His habits were first sown, even as a seed,

Who that shall point, as with a wand, and say,

'This portion of the river of my mind

Came from yon fountain?'

William Wordsworth, The Prelude

The one way of tolerating existence is to lose oneself in literature as in a perpetual orgy.

Gustave Flaubert

In comparing our lives to two different means of transit, a stairway and a river, Emerson and Wordsworth cut to the heart of the problem faced by anyone who sets out--as I do now--to tell the story of my life. Looking down the stairway of my ancestry, or (to switch the metaphor) into the roots of my family tree, I cannot get very far below my grandparents. Two years ago, at the age of 82, I launched a family website that reaches back just barely beyond three generations. My maternal great-grandfather was a wealthy Philadelphia merchant; my paternal great-grandfather was the son of an Irish tenant farmer who left his native village of Galbally in County Cork, Ireland, at the age of 14, in 1847, right in the middle of the Great Famine, and took ship for America, where he managed to raise a family by subsistence farming and small returns on a tobacco whose leaves were just good enough for wrapping cigars. Such is the wondrous weave--or the weirdly entangled roots-- of my genealogy.

But since Jean Jacques Rousseau launched the story of his life in the Confessions by recounting the courtship of his parents, let me say a few words about the courtship of mine.

Though second cousins, they were both in their twenties when they met for the first time at the Boston area wedding of a mutual cousin in December 1923--just over a hundred years ago. Almost twenty-four, Kathleen was tall, lithe, dark-haired, lovely, fun-loving, and doubtless a very good dancer. Three years earlier in Soissons, France, where she had worked with the American Committee for Devastated Regions in the wake of World War I, she had taught French schoolboys how to waltz and fox-trot. Altogether, she was quite enough to dazzle any young man in quest of romance, as Roy was at the age of 28.

And Roy himself knew how to dazzle. Tall, muscular, and stylish, with coal black hair, sparkling blue eyes, and a large, well-trimmed moustache, he might have passed for Ronald Coleman, hero of the silent screen. But looks were only part of what Roy had to offer. He was lively, witty, charming, and deft at seizing precious opportunities. By the time the wedding reception ended, he had made a date to see Kathleen again. They were engaged by the following April, and here they are at my grandmother's seaside house in North Scituate, Massachusetts, in the early summer of 1924:

They did not marry until January of 1925, when they headed north for a honeymoon of skiing and luxuriating at the Chateau Frontenac in Quebec, Canada, perched high on the banks of the mighty St. Lawrence. But in the previous summer they had to endure a whole month apart. While Kathleen supervised young girls at Camp Quinibeck (now defunct) in Fairlee, Vermont, Roy worked from dawn to midnight in Boston, sweating through a sweltering August (well before any air conditioning would cool offices, hospitals, operating rooms, or anything else inside) to build his practice in obstetrics and gynecology.

Thanks to a batch of letters that my sister Peg found in the attic after my mother's death (at the age of nearly 102), I know exactly how they felt. When they kissed goodbye on July 30, 1924, neither of them fully realized just how painful the separation would be, though Kath writes in her very first Quinibeck letter, "Darling, the nights will be the worst." Yet from the relentless ache of their longing for each other through what finally seemed to both an eternity--"18ages -- 14 1/ 2 eons and 39 3/4 dynasties," wrote Roy near the end of the month--sprang one letter after another for almost every single day of the month. We who can reach other instantly by cell phone, email, or text message can hardly imagine how precious a letter could be when it was almost the only means of communication between one place and another. Roy and Kath treasured each other's letters like gold. Through letters that somehow remained impeccably chaste they hugged and kissed with great big X's and O's; through letters they told their love in a hundred ways, never managing to tell all they felt, no matter how hard they tried: "I love you so much," writes Kath, "I just can't imagine what would describe how much -- except perhaps if you can imagine all the worlds and air and space filled with my love it would still feel like bursting because there wouldn't be room for anywhere near all of it."

They could sometimes talk by telephone, of course, since the phone had been around for nearly fifty years, but in the rural Vermont of 1924, phones remained scarce, and reaching anyone at Camp Quinibeck from Boston took an extraordinary combination of patience and luck. The camp had just one phone ("Fairlee 20"), so Roy had to call when Kath was most likely to be near that phone, which was Sunday after lunch at 2:00 P.M. But all he could do then was place the call with an operator,. who would then try to put it through for him in a process that might take up to an hour. On August 11, a Monday, he tells Kath what happened the day before:

If you hear of my arrest you will know that I have murdered one or several telephone operators. Yesterday I worked from five A.M. until two P.M. when I rushed home and called "Fairlee 20" -- I was just dying to hear your voice again, Darling. I had an unfortunate case at St. Margarets and told the toll operator to speed up the call. At 2 50 I had to cancel the call -- my heart just ached with disappointment and rage -- and fly to St. M's. . . .

My heart just ached with disappointment and rage. But it survived, as he did, and they went on to marry and bear seven children before finally begetting a pair of twins in 1939: my twin brother Tom and me.

We joined what became a proliferating clan. Looking up into the canopy of the family tree, I see literally scores of branches, for six of my seven siblings spawned a total of thirty children beside my own two kids, and my four grandchildren--just now ranging in age from 15 to 20--will no doubt add their share. But all I can do is list them and their myriad cousins on the family website, which I leave to them as a digital legacy.

On the other hand, I should say a little more about the Emersonian stairway leading up to my own set of steps.

At 46 Eliot Street in the metropolitan Boston suburb of Jamaica Plain, the house where I spent the first sixteen years of my life had five sets of stairs leading all the way from the basement to the third floor, including a set of back stairs that led from a landing in the two-story front hall down to the kitchen. So Emerson's stairway first of all reminds me of the countless times I spent tripping up and down those stairs, literally having the run of the house. But of course Emerson is using a flight of stairs to say something fascinating about memory. No matter how far my memory stretches, I cannot recall the moment of my birth, anymore than I can precisely foresee the rest of my life, or what my children and grandchildren may do after I leave. So instead, let me plunge into the middle, or rather leap to near the end, where I am now, and then work my back. How did I get here?

"Here" is a landing or even summit of sorts near the end of my life. As I write these words at the ripe old age (forgive the hoary cliché, please!) of 84, I am savoring a rare pleasure. In the Christmas 2023 issue of the New York Review of Books, my own latest book--Politics and Literature at the Dawn of World War II-- is lauded at length for probing the "punctual literature" provoked by the outbreak of World War II: works of literature that rival history by re-creating the experience of a time before anyone knew how the war would end. In America, the New York Review of Books is the most prestigious as well as the most judicious assessor of fiction, poetry, and books that generally qualify as academic. Since it reviews only a tiny fraction of the 12,000 academic books published each year, it is just about the toughest nut that an academic book can hope to crack. So finding this essay in the Christmas issue of the New York Review feels not just like the perfect Christmas present but a little like winning the lottery.

But since Rich's review--generous and comprehensive as it was--says nothing about my analysis of the relation between history and literature in the Prologue to my book, I took the liberty of asking for a verdict on it from Charles Maier, a renowned authority on European history who has long taught it at Harvard. In an email of December 22, 2023, Charles wrote:

Your prologue is important. Being of a critical spirit, my reaction is to interrogate every assertion--"Is that really true?" etc. Most of it is, but I would try to "complexify" some of your generalizations.

Since this is exactly the spirit with which I judge any piece of writing presented for my opinion, I could ask for nothing more. Thank you, Charles. I shake your hand.

So how did I come to write this book about literature and war? Let me briefly explain.

Since I was born on April 22, 1939, just over four months before Hitler's invasion of Poland ignited World War II, war found its way into my earliest years. War at a distance, that is, since all of the fighting took place across the Atlantic, far from Jamaica Plain. But etched on the copper plate of my memory from that warring time are three indelible vignettes.

First is a night in the winter of 1944, when two young soldiers came to our house to collect my sisters Joan and Peg, then in their late teens, for a night on the town. (The date was probably arranged by the Boston branch of the United Service Organizations--USO). I can see those soldiers even now from the little square purple velvet footstool where my four-year-old self sat in our living room. Standing before us, Al was tall and slim, Dick a bit shorter and stockier, and in their spanking dress uniforms they both struck me with awe.

Fast forward, then, to June of 1944, when my five-year-old self came home one day from kindergarten (we could easily walk home from school) to find Peg reading a letter by the light of the three-sided bay window at the far end of the dining room. The letter, she said, came from Al, and it reported that Dick was dead. I now realize that he must have been one of the 29,000 American soldiers killed in the allied invasion of Normandy, but at the time all I could do was register his death with a kind of click in my brain. Not grief, for I scarcely knew him, but the mildest--as well as somehow the most indelible--of shocks.

The second memory comes from an afternoon in early August of 1945, right after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended the second World War by forcing the Japanese to surrender. Though I knew nothing of those facts then, I can still see now on the kitchen table of our house the Boston newspaper whose big black headline shouted, THE WAR IS OVER. By then I must have already read many other words, but those are the very first words that I can distinctly remember reading.

Finally, I remember the game we called "war"--insofar as it can be called a game at all. We played it, I think, right through the 1940s, well beyond the ending of what had inspired it.

It was not so much a game as a spasm of frenzy with no rules at all. Whenever a fierce quarrel broke out in the midst of our other games such as baseball, someone would simply shout, "WAR!" That declaration alone would set us off. Taking sides at once, we felt absolutely free to throw anything we could find--sticks, stones, tools, toys-- at the other side. So far as I can recall, nobody ever socked anyone else, and miraculously enough, nobody got seriously hurt by a flying missile. Mostly, in fact, our wars were simply shouting matches that ran down after a minute or two, at which point we would flop down, catch our breath, get up again, and resume whatever game we had been playing. It has since occurred to me that the world would be vastly better off if all wars were fought by shouting alone.

At the age of fifteen, a few years after we stopped playing war, I wrote for the Botolphian magazine of Boston College High School a poem called "To War" that channeled the voice of a mother:

My son has gone to war

To the trembling battlefield of love and hate . . .

Since the U.S. was then caught up in the Cold War, I couldn't resist a pair of metaphoric allusions to the well-known icon of Soviet Communism:

What hammer stuns us to brutality?

What sickle severs our perception?

My own perception of war at this time was of course pretty hazy, and though my oldest brother Mike once served as a Marine officer and two other brothers trained for the National Guard, I never spent so much as a day in any of our armed services. When I turned 18 in April of 1957, I duly registered for the draft, but by the late 1960s, when I might have been drafted for the war in Vietnam, I qualified for deferment--whether rightly or wrongly-- because I was then teaching at Dartmouth.

During the rest of my almost forty years at Dartmouth, I wrote about various topics other than war, but after my retirement, when I set out to write Hospitality and Treachery in Western Literature, I felt bound to start with Homer's Iliad, which ends up with one of the most powerful scenes of wartime grief ever written. After Achilles kills Hector, the very last of Priam's sons to die at the hands of the Greeks, the old king goes to Achilles, kneels at his feet, kisses "his terrible, man-killing hands," and begs him for the body of his son. "Revere the gods, Achilles!" he says. "Pity me in my own right, remember your own father!" (Iliad, trans. Robert Fagles 24. 561, 588-89). Priam thus prompts Achilles to remember not only his own father but also his beloved friend Patroclus, whom Hector had previously killed:

And overpowered by memory

both men gave way to grief. Priam wept freely

for man-killing Hector, throbbing, crouching

before Achilles' feet as Achilles wept himself,

now for his father, now for Patroclus once again,

and their sobbing rose and fell throughout the house.

(Iliad, trans. Fagles 24. 594-99)

Sobbing for a beloved father, a beloved son, and a beloved friend, sobbing for all the pain that each has suffered from the merciless cycle of killing and retaliation, these two men weep also for us. At this very moment in our own history, when grief for the many thousands of Palestinians killed by the Israeli bombing of Gaza clamors to drown out grief for the hundreds of Israelis killed by Hamas, could any Israeli ever weep with a Palestinian as Achilles did with Priam? Or are the two sides doomed forever to attack and revenge, to kill and retaliate, to relieve their desperation--as Milton's Satan does in Paradise Lost--"only in destroying"?

Without even trying to answer that question, let me finish answering--at least for now--the question of how I finally came to write a book about war. Quixotically enough, it originated from an impulse to write about myself. Since I was born in 1939, I set out to write a detailed history of that year, with my own birth--preposterously enough--tucked into it as a mini-event. I took my cue from the opening chapter of Melville's Moby Dick, where Ishmael reports his decision to go to sea as something sandwiched between

more extensive performances. I take it that this part of the bill must have run something like this:--

"Grand Contested Election for the Presidency of the United States."

"Whaling voyage by one Ishmael."

"BLOODY BATTLE IN AFGHANISTAN."

With absolutely no training as an historian but with lots of help from Wikipedia, I read my way from the Munich Agreement of September 30, 1938 through Hitler's invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, drafted five chapters on the results, and showed them to a good friend named Phil Pochoda, a thoroughly seasoned editor of academic books. His verdict hit me like a rock. As he joined me for lunch one winter day at a pub in Lyme, New Hampshire, where he now lives, he dropped just two words: "potted history." Which it was. However readable it might be, it was all distilled from secondary sources, with no new ones and no new take on the old.

But as I slipped into the driver's seat of my car after that lunch, I had a minor epiphany. I was not an historian, after all, but a critic and scholar of literature. Since I now had a pretty good grip on the political history of 1939 and the outbreak of World War II, why not shift the focus back to literature? Why not see how the dawn of that war inspired writers such as Hemingway, W.H. Auden, Bertolt Brecht, and Evelyn Waugh? Inevitably, I would have to probe the relation between literature and history, which--as noted above-- I ended up treating at length in the prologue to the book as well as briefly elsewhere. But my chief subject, I decided, would be literature--as a rival to history.

After drafting nine chapters of this book and sending them off to Bloomsbury Academic, I got mixed reports from two anonymous readers. While both liked the book, one of them thought I should do more with the historical context, that I should juxtapose history and literature by setting, for instance, Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls beside an historian's account of the Segovia Offensive in the Spanish Civil War, on which it is based. So that is just what I did, and the book was promptly accepted.

By amazing coincidence, the unfolding events of our own time re-animated the historical moment explored by this book. In February of 2022, when I was polishing the final version of the Prologue, Vladimir Putin's invasion of Ukraine re-enacted what Hitler had done to Czechoslovakia and then Poland in 1938-39. So I couldn't help making this link explicit as I sent off the final version of the proofs.

Behind this brief sketch of what finally led my 80-year old self to write a book about war is a much longer story about how I came to be a writer. Not a famous writer, of course, nor even what is now called a public intellectual, but at least a man with something (I hope) interesting to say about his own experience of learning to read, write, and teach literature at a time when literature and the humanities in general are more than ever threatened by our obsession with more marketable subjects such as STEM. Given the present cost of higher education, which is rapidly approaching six figures a year at top universities, who needs the humanities--or literature?

One answer is that STEM has lately begun squeezing an A (for Arts) into its acronym, so that it becomes STEAM, aka Science-Technology-Engineering-Arts-Mathematics. But under this arrangement, all arts are steam-pressured between Engineering and Math--as if "arts" were a lunchtime class on finger-painting stuck between Engineering 302 and advanced Calculus. Sorry, STEMers, you can't buy me off with finger painting, and I can't find either literature or the humanities in your catchy new acronym. To me it's just a puff of industrial steam. So from here on I will use the original acronym: STEM.

So once again I ask, "Who needs the humanities?"

Having tried to answer this question recently in the American Scholar, I won't repeat the answer here except to wear the heart of it on my sleeve. I have taught and studied literature throughout my adult life for the simple reason that I love it. One big bad reason why the humanities are shedding so many students right now is that too many of its professors--especially professors of literature--don't love it. They strive instead to enlist it in wars against racism, misogyny, homophobia, capitalism, power in all forms, and every kind of foundational assumption which they believe literature is ordained to deconstruct. Though generally familiar with such landmark studies as Roland Barthes' The Pleasure of the Text (1975), they stigmatize reading for pleasure: if you savor so much as a single well-wrought sentence, they believe, you sacrifice the political value of a text--especially its deconstructive energy--to a purely aesthetic frisson that can feed only the jaded appetites of the elite, not the hungry mouths of the politically oppressed.

If that sounds both reductive and reactionary, let me give you a good example of exactly what I mean.

Almost fifty years ago, in an article published by the Massachusetts Review in 1977, the Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe threw a rhetorical bomb. He lobbed it at Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness, the story of a would-be emissary of European light whose lust for ivory among natives of the Belgian Congo drives him into madness and human sacrifice. But in Things Fall Apart (1958), his first novel, Achebe implicitly challenged Conrad's version of Africa by re-creating the pre-colonial life of southeastern Nigeria and its European invasion in the late nineteenth century. In 1977, his article made the challenge explicit. Meticulously analyzing Conrad's novel, he clearly showed how much it is driven by ignorance of native customs and the natives themselves, who barely qualify as human beings: they are simply "not inhuman." And from this analysis Achebe concluded that "Joseph Conrad was a thoroughgoing racist."

But was he really a thoroughgoing racist? Could that epithet fairly describe a writer whose novella--whatever its blind spots-- had ruthlessly undermined the assumption that white men are inherently superior to blacks? Years after publishing his charge, Achebe himself in my hearing came close to retracting it. In the winter of 1990, when he visited Dartmouth as a Montgomery Fellow, I had the pleasure of meeting him at a seminar for Dartmouth faculty, and we could hardly resist asking about The Heart of Darkness. His response was telling. Besides admitting that he had overstated his case against Conrad, he stated that Heart of Darkness still deserves to be taught and read, just as he read it himself at the age of 14. And he clearly implied that it had played an important part--positive as well as negative-- in his own literary education.

It has much to teach any aspiring writer. Consider just this single sentence about the River Congo:

Going up that river was like traveling back to the earliest beginnings of the world, when vegetation rioted upon the earth and the big trees were kings.

This one sentence could easily generate a whole class if not a whole course in the art of writing. First of all, the parallel structure of its opening clause neatly brackets voyaging through space with travelling through time. Though I have co-authored several textbooks on grammar and rhetoric, I have belatedly realized something never mentioned by any of them: one very good way of learning to write well is quite simply listening to the body and reviving its earliest moves. Long before we learn to talk, let alone to write, we learn coordination, including parallel structure. Instinctively we start to crawl by reaching forward first with one hand and the opposite leg, then with the other hand and the other leg, and so on. Essentially, Conrad's sentence re-enacts our very first moves. It starts by crawling along with parallel phrases about space and time.

But that's just for a start. Consider what Conrad does with metaphor in what comes next, when "vegetation rioted upon the earth." Could anything be more startling than this way of picturing vegetation, which we commonly visualize as just sitting there and vegging out? In a poem called "To His Coy Mistress," Andrew Marvell once compared his love to a huge, sluggish vegetable that would grow "vaster than empires, and more slow." But if you've ever traveled in a tropical country, as I have, you can see how fast the roads can be overtaken by roadside shrubs, which in the Yucatan (for instance) have to be cut back almost every day. Whether or not you've ever seen such runaway growth, Conrad's metaphor ignites in your imagination a whole new picture of vegetation as something not just alive but running wild.

No charge of racism, however justified, can erase that verbal picture--or the picture of big trees as kings. To study a sentence such as this is to learn what I have long believed. As teachers of literature, nothing we do is more important--more important-- than cultivating within our students a profound and lasting admiration for the beauty and power of the English language as deployed in works of literature that have stood the test of time. I don't for a moment underestimate or overlook the power of literature: its power to unmask hypocrisy, self-delusion, cruelty, and all of the ways in which we may blind ourselves to our own complicity in oppressing the powerless. But I firmly maintain that literature works quite as much by means of beauty as well as power, and that great literature embodies both.

So the question now commonly, anxiously, and repeatedly asked--"Why do we need the humanities?"--is exactly the question I have tried to answer here, by telling my own story, How did I come to know and love language, literature, and the art of writing? When all three seem almost eclipsed by the wizardry of Artificial Intelligence and ChatGPT, which promise to do all our reading and writing for us, can my story be anything more than a dead letter? I hope not. And just as strongly, I hope to explain how an academic writer learned to practice throughout his life the art of writing--which I have never presumed to master--even as the professoriat rose, like figures basketed under a vast balloon, to the almost unbreathable air of high theory, leaving far behind them what Yeats once called "the foul rag and boneshop of the heart."

Safely out of that lofty basket, let me cycle from where I am now back to what I might call the beginning of my life. If the mind is a river, as Wordsworth suggests, its very flowing makes it different from one second to the next, as first noted by the ancient Greek Heraclitus, who also insisted that everything flows (panta rei), which must be the pithiest aperçu of all time. (Just imagine making your name for millennia by mere fragments like that!) And even if the waters of the mind had somehow remained the same, how could I identify all the tributaries that flowed into it and thus quite literally influenced it? Impossible. But along with my parents, my siblings, my wife, my children, and the scores of other people who have done their part--often unwittingly--to nurture me, one stream of metaphorical water has kept me steadily afloat: literature. Which is why, besides Emerson and Wordsworth, I've also quoted Flaubert on the orgiastic pleasure of getting lost inside it.

When I was a plump frog of about ten, I loved nothing better than flopping around in water. Not exactly swimming, just hanging out--occasionally paddling, flapping, or floating--especially in a large but shallow pond called Ponkapoag, in the Blue Hills Reservation south of Boston, where my mother often took us in the summer. Doubtless I was unconsciously revisiting the amniotic waters of her womb, as any good Freudian shrink would tell you. But even the memory of that, if there were such a thing, would have been complicated by the fact that I shared the womb with my twin brother Tom, with whom I went on to fight nearly every day of our childhood--mostly by wrestling on the hardwood floor of our common bedroom. (We get on fine now, thanks.) Rather than evoking the womb, then, the lovely waters of Ponkapoag seem to me rather to prefigure what lay ahead of me: the ocean of literature in which I have happily swum for the past seventy years.

Its waters never dry off. I can hardly see anything without looking through them, as if they had turned into lenses. Whenever I look up at a clear night sky, I think of a line from Joyce's Ulysses: "the heaventree of stars hung with humid nightblue fruit." Whenever I write to a friend that I haven't seen, phoned, or emailed for a while, I steal the title of a poem by Yeats--"After Long Silence"--to say "Greetings after long silence." And as I try to conjure up my very earliest memory, I think of what Wordsworth aimed to do in The Prelude, the long autobiographical poem that he spent much of his life writing and re-writing. Among other things, he said, he aimed to re-awaken

lovely forms

And sweet sensations that throw back our life

And almost make our Infancy itself

A visible scene, on which the sun is shining.

Remarkably enough, these words help to retrieve my own earliest memory, which I am pretty sure dates from the spring of 1940, when I was just one year old. Tom and I had been put into a playpen on the side porch of our house--a porch that led by a short flight of wooden steps down to a gravel driveway. Beside the steps, a golden spray of forsythia spilled out under a bay window, and though I know this only from later experience, I think I dimly noticed it even then. But what I clearly remember is the moment when a shiny black car pulled up to the bottom of the steps and out of it stepped a man in a dark suit with coal black hair and matching moustache--a man we instantly recognized. "Daddy, Daddy," we shouted as he climbed the stairs and took us each in his arms.

Like all early memories, this one now takes its place with later knowledge. After many years, I gradually discovered that the vibrant, genial, affectionate, irrepressibly voluble man I knew as my father for the first 53 years of my life (he lived to be 98) spent most of his own life secretly nursing a broken heart. In late February of 1939, just under two months before Tom and I were born, my parents' firstborn child--Roy Heffernan, Junior--died of pneumonia after having his appendix out at the Faulkner Hospital of Jamaica Plain. Just 13 years old, Roy was the victim of cruel circumstance. In the very year of his death, a German pathologist named Gerhard Domagk won the Nobel Prize by discovering the first of the antibiotic sulfa drugs--Prontosil--that could successfully treat bacterial infections. But this drug was not available in time to save Roy's life. And the thought that he died in a hospital, the very place where my father had delivered scores of babies (he practiced both obstetrics and gynecology in various Boston hospitals for some fifty years) could only have doubled the shock of his death.

In chapter 2 of James Joyce's Ulysses, a character named Stephen Dedalus--a fictionalized version of Joyce's younger self-- teaches a class of unruly boys at a grammar school in Dalkey, a coastal town ten miles southeast of Dublin. Questioned about algebra by a rather slow student after class, Stephen silently ponders the inner life of the boy--and of himself: "Secrets, silent, stony sit in the dark palaces of both our hearts: secrets weary of their tyranny: tyrants, willing to be dethroned." Dad never dethroned his secret. On the contrary, as I learned only after his death, he actually told my mother right after Roy's death that he never wanted to hear his name again. Unlike my mother, who wept freely, he could not cry. His eyes were sealed by the iron habit of self-discipline, and all he could do with his grief was to bury it--alive. In all the years I knew him, I never heard him speak Roy's name, nor heard anyone else speak it in his presence (though of course I heard it mentioned otherwise). But in 1955, when my older brother Mike phoned my father to say that he and his wife were naming their firstborn son Roy, Dad could not speak. As Mike later learned from our mother, the man of words for all occasions could do no more than silently hand her the phone as his tears spoke for him. Some years later, when I first read Byron's Child Harold's Pilgrimage, I found a line that perfectly captured my father's inner life. In Canto III of this poem, a canto written in the spring of 1816, Byron writes of all who have mourned those freshly killed--the previous June-- in the battle of Waterloo. Like a day persisting through storms that block the sun, Byron writes, "the heart will break, yet brokenly live on."

Dad hid his broken heart so well, however, that his pain never became mine, or passed to any of his other children. On the contrary, he gave me what was probably his most precious gift: his love of language. At the family dinner table each night, he often played what he called "the word game." Starting with the letter A, he sprang on us a sequence I can still remember--at least up to E: acidulous, blatant, clandestine, diffident, and even eleemosynary--that wriggling eel of a synonym for "charitable" known mainly to speakers of legalese. Since none of us recognized any of these words, he would carefully explain each one, and I in turn digested his definitions along with each meal.

Quite as much as language he loved literature. With scarcely more than a high school education at Somerville Latin School (and just one year at Boston College before entering Tufts Medical School, which in 1913 required no B.A.), he loved reading, and he also loved quoting such things as Shakespeare's Hamlet, Coleridge's "Rime of the Ancient Mariner," and Dickens's Oliver Twist. His concentration was amazing. Many years back, on a morning when our house in Milton, Massachusetts was swarming with preparations for the wedding of my older sister Peg, Dad quietly sat in his favorite living room chair with a book on his lap. Dumbfounded by the sight, a gracious African-American woman who had been hired to help us that day told my sister, "Your father is the most decomposed man I ever saw." Fortunately, however, he stayed fully composed until he died in December of 1992.

Long before then, my mother had started composing me. So far as I can recall, it was she who read to me in her bed the first book I ever saw: Mother Goose. (I also remember trying to read for myself in that same bed Grimm's Fairy Tales and barely getting through its first sentence.) At this time Tom and I slept together in a small room at the front of the house that was wallpapered with Mother Goose characters, and I once had a waking dream in which they all waddled around and prattled to me: a bit startling but not at all scary.

Though I can't remember learning to read, I do recall learning the word "beautiful" one day in kindergarten class at the Agassiz School of Jamaica Plain (now long gone) and I can also vaguely remember learning to write under the tutelage of Miss Cleveland, a middle-aged woman who bravely taught a class of something like forty first graders. (Perhaps as a result of the strain, she dropped dead of a heart attack the following year.) By this time, in any case, I had begun to be fascinated by words such as "bold," which Miss Cleveland once flung at a classmate: "You are a bold, bold boy!" she said. Later on, of course, I learned that "bold" could mean not just rudely defiant but also daring, venturesome, and fearless. (A pilot once told that there are old pilots, and bold pilots, but not many who live to be both.)

The first books I can remember reading on my own were all about the Hardy boys, a fictional pair of young detectives concocted by a team of ghostwriters named Franklin W. Dixon and featured in a series of books first published in 1927. But until about the age of 12, most of my reading consisted of comic books, especially of the Disney characters Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse. It was in one of those comics that I first met one of my favorite words: "crave." "I crave action!" said Donald Duck. That was all I needed to make the word my own.

The first "grownup" book I can remember reading was an historical novel: Mutiny on the Bounty (1932) by Charles Nordhoff and James Hall. Based on the celebrated mutiny of British sailors against the tyrannical Lieutenant William Bligh in 1789, the novel fascinated me. Aptly enough, I read it by the sea in July of 1952, when my parents rented a beach house in Duxbury, Massachusetts. After riding the waves and soaking up the sun each morning on the beach, I spent the afternoon with Bligh and his mutineers. What could be better?

It must have been about this time that I started--just barely started--to think about the art of writing, though I never put it into those words. At the risk of sounding insufferably precocious, I had actually written my first poem in the third grade. By then Tom and I had been taken out of the Agassiz school and sent to an all boys' Catholic school called Walnut Park in Newton, Massachusetts, where we were taught by the Sisters of Saint Joseph. Unlike the Agassiz school, it offered a fully equipped playground, large grassy playing fields, small classes, and even an indoor swimming pool. But when one of the nuns told us one day how privileged we all were, I had absolutely no idea what she was talking about. Ah, the blissful ignorance of jeunesse dorée!

The nuns were long on God and saints and North American martyrs, adequate on mathematics, and fairly short on just about everything else. (One day we were each asked in turn to answer the question "Who made me?" with the steadily repeated answer, "God made me," which of course made no allowance for our parents. ) But one of Sister Tracy's lessons about angels inspired this little quatrain, whose sheer banality has made it unforgettable:

St. Michael fought the devils;

He fought the devils well;

He beat them and he thrashed them

And sent them all to hell.

Though much impressed with these lines, Sister Tracy was not so happy with a little jingle which, after circulating around the class, was for some reason attributed to me:

Glory, glory, hallelujah

Hit the teacher with a ruler,

Bop her off the bean with a rotten tangerine,

Our truth is marching on.

Since I have no recollection of writing these lines, I must have heard them somewhere and then passed them on (they've been floating around for years, and versions of them can now be found via Google). In any case, since I was charged with originating the quatrain, I was made to write a little essay on "The Need for Respect" that I have totally and mercifully forgotten.

After the sixth grade at Walnut Park, Tom switched to middle school in Jamaica Plain and I went to Boston Latin, near the city's Kenmore Square, a renowned public school taught by men (and men only then) far more demanding than the nuns had ever been. Starting in the seventh grade as a lowly "sixie" (like British public schools, Latin numbered its grades from six to one instead of 7 through 12), I coped as well as I could with the culture shock of being suddenly surrounded by "non-Catholic" boys of various faiths, colors, and ethnicities--and almost all ranging from restless to bold, with occasional mutinous roaring at any teacher they found at all vulnerable. Standards were fearfully high. At school assemblies our short round headmaster, George Mc Kim, never failed to remind us that "a Latin School boy does three hours of homework every night." Though meant seriously, that was a joke, at least for me, because I could never finish my homework in that amount of time. And in spite of my nightly labors, I can still remember flunking a history quiz on which I wrote--among other things-- that the chief engineer responsible for the Panama Canal was Charles Boyer. Having somehow confused the famously suave French actor with George Washington Goethals, I desperately wanted to write something on that question. (Years later I learned all about Goethels from David McCullough's mesmerizing Path Between the Seas.)

Among homeroom classmates who also flunked that quiz (as quite a few did) was a kid named Dratch. Short, plump, red-faced, and crowned with spiky black hair, he was one of several Jewish boys in the class, but hardly among the brightest of them. When he got his quiz back, he stood up in the aisle just behind me and--clearly distraught at what his parents would have to say--began to weep. But just ahead of me in the front left corner of that classroom I can still see a chubby, happy-go-lucky Black kid named Bansky, who turned around and grinningly said, "Dratch, we'll flunk together!" Whereupon Dratch let out a fresh wail and a fresh Niagara of tears.

The top two students in that class were also Jewish kids, but neither one got top grades because they were damn near impossible to get. Case in point: if you passed all your courses in a term, you got "approbation." If you averaged at least 70, you got "approbation with distinction." I was among the few who occasionally got "approbation," but nothing higher--though I think one or two of the Jewish kids did.

My favorite teacher at Boston Latin was Conrad Pappas Jameson, an avocational actor who poured his resonant voice and captivating theatricality into the teaching of Latin. I was hooked as soon as I first heard his booming words heralding his entrance into the classroom on the very first day of class, With his black wavy hair and his volatile temperament (due partly, no doubt, to the Greek ancestry on his mother's side), he kept us entertained as well as instructed: a perfect combination of the Horatian "utile et dulce," useful and sweet.

Outside of class, by happy coincidence, he regularly appeared along with my father in zany skits mounted by the Clover Club of Boston for its occasional dinner meetings. (The club liked to have one or two professional actors to spice up the proceedings). One night my father invited me to have dinner with Jameson and the rest of the cast after a skit rehearsal. So I got to know him as a friendly mentor, and he was one of the first to vet my juvenilia, which he found over-subjective, as indeed they were at the time, but also perhaps promising.

I recall just two kinds of writing that I did during my two years at Boston Latin. One was a regular exercise in summarizing assigned by Mr. McNamara, who taught English. Given a few paragraphs to read for each class session, we were told to summarize them in a single paragraph and set that down in our notebooks, which were sporadically checked. Meeting us every day right after lunch, when I suppose he was feeling just about as drowsy and/or dyspeptic as the rest of us, he would settle his hefty, tweed-swaddled bulk into the chair behind his desk and growl something like,

"Antimachus, let's have your notebook."

As often as not, the piccolo-piped answer would be,

"Haven't got it, sir."

To which invariably came the reply:

"Take a plum."

Meaning a zero for the hapless Antimachus in Mr. McNamara's own notebook.

If a student was lucky enough to have his notebook, Mr. McNamara would take about thirty seconds to paw through its pages and then award some number higher than zero, probably 8 out of 10--a default score. All he wanted to see was that at least some of the lines in the notebook were filled with words, which of course he never bothered to read.

Strangely enough, I can't remember ever having my notebook called and thus examined, or rather skimmed, but I do remember writing my summary for every class, and actually taking some satisfaction from composing it. Besides learning to comprehend what I read, I also started learning how to prioritize one point over another in my own writing--learning what to include, what to exclude, and what to feature. I thus began to practice the art of subordination, which is essential to writing well.

The only other kind of writing I recall from these years was an in-class composition assigned by another English teacher with something like the following prompt: "Everything looked clean and fresh after the long rain." Are you kidding? I was stumped. The only thing good about that prompt was the simple, hard (though unintended) lesson that you can't make a piece of writing out of marshmellow fluff. You've got to have meat, flesh, and bones, or at least a few telling facts. As Lear tells Cordelia in the first act of King Lear, "nothing will come of nothing."

In the fall of 1952, after two years at Boston Latin, I brought a little more than nothing to my first year at Boston College High School, which was then largely staffed by Jesuit priests (now long since replaced by unordained "lay" teachers) and partly conducted at its original building on Harrison Avenue in South Boston. (With freshman and sophomores taught there, juniors and seniors met on the new campus at Columbia Point on Morrissey Boulevard, where its urban copse of its handsome new buildings stand today.)

Luckily enough, I was put into the freshman Honors class (Class 1C) under the genial tutelage of Father Ecker, where my two years of previous work on Latin allowed me to sail along comfortably beside classmates learning it for the first time. Thanks to that and to whatever study habits I had acquired from my years at Boston Latin, I did so well that for a late spring assembly of the school, I was the first student called upon to deliver a speech. Not of my own making, that is: we had all been told beforehand to memorize any speech we chose and have it ready to deliver if called upon to do so. When speech time came at the assembly, I suddenly heard Father Francis Gilday call upon "James Heffernan of the Class of 1C." Struck by a lightning bolt of adrenaline, I stood up, marched to the stage, and recited Patrick Henry's "Call to Arms" right up through its boffo final words: "Give me liberty or give me death." Roundly applauded, I felt for the very first time the power of the spoken word.

For the summer after my freshman year, Tom and I returned to North Woods, a YMCA camp on Lake Winnepesaukee in New Hampshire, which we'd been attending for eight weeks every summer since we were seven (having started with four weeks). Since we were now 14, we gradually transitioned from campers to "counsellors in training," which meant learning how--in a fairly haphazard way-- to supervise other kids. I learned just enough to compose the first piece of writing I ever published: "Confessions of a Camp Counselor" in the Botolphian. Leavened with feeble efforts at wit and somewhat enhanced by an editor who retouched it without consulting me, it made me just about as proud then as it now makes me wince.

The second editor I had turned out to be my first and only ghost-writer. Though I can't recall his name, he ran a local paper based in Milton, Massachusetts called the Milton Transcript, which (as Google reports) is now called the Milton Record-Transcript. In the fall of 1955, when my parents moved from Jamaica Plain to Milton, I went to the office of this newspaper, volunteered to write for it, and was offered the chance to submit articles at the rate of one dime per column inch. (My son Andrew, who writes about fitness for magazines like Men's Health, has recently bagged as much as $2.27 per word.) After the paper had run a few of my articles on local affairs (including a long one drawn from the memories of a retired fireman), the editor asked me to "cover" a town meeting in Milton, which I promptly agreed to do. But just before the meeting I discovered a conflict: on the Saturday for which it was scheduled, I was slated to join the BC High debate team for an out-of town tournament. What to do? My mother, of course! Who kindly offered to take notes at the meeting and give me what I needed.

Unfortunately, the sharp-eyed editor did not fail to notice that I had missed the meeting. On top of that, my mother's notes on the long-windedness of at least one of the speakers did not furnish the kind of material the editor wanted. What he wanted was an awestruck report on my first experience of small-town democracy. So a few days after the meeting, he published under my name on the front page of the paper a piece that started out something like this:

Last Saturday, for the first time in my life, I attended a meeting of Milton's good people in the Town Hall on Canton Avenue. After hearing all kinds of citizens--from doctors and lawyers to shopkeepers and housewives--discuss and debate the leading issues of our town, I wish every teenager in America could have been there with me to witness democracy in action.

Pure drivel, of course. Let the record show, in case anyone ever tries to find this item in the Milton Transcript archives, that I never wrote such stuff for publication, though of course I have just now channelled the voice of that ghost-writing editor.

In the fall of my junior year at B.C. High, when it moved from South Boston to the new campus at Columbia Point, I first encountered the eloquence of Cicero. Not just the leading orator of ancient Rome but one of the greatest orators of all time, Cicero poured all of his speechmaking talents into an oration which, as I have lately learned from Mary Beard's book SPQR, hit the Roman Senate like a nuclear bomb. Early in 63 BC, just after beating out Catiline in the consular election, Cicero learned that the near-bankrupt aristocrat was plotting to assassinate him along with several other elected officials and burn the city so as to cancel all debts --including those of Catiline himself. It took months for Cicero to gather convincing evidence, but on November 7 of 63 BC, he delivered a speech that made the Senate realize just how dangerous Catiline was.

I have long cherished its opening words--and never more so than right now, when the prospect of a second presidential term for Donald Trump scares me quite as much as Catiline ever scared Cicero:

Quo usque tandem abutere, Catilina, patientia nostra?

Quem ad finem sese effrenata jactabit audacia?

Try as I might, I've never managed to translate these resounding lines to my satisfaction, but here's about the best I can do:

How long will you abuse our patience, Catiline?

To what boundary (or limit) will your unbridled audacity fling itself?

OR

How far will your unbridled audacity go?

Though my second version of the second line is obviously more idiomatic, I've always wished there were some way of catching in English the picture drawn by the original line--of Catiline as a wild and rearing horse, totally out of control. Just like Donald Trump right now.

I never fully mastered Latin and its literature, which I studied every year from the seventh grade up through my freshman year at Georgetown, but paradoxically, studying Latin taught me a lot about the English language. Unlike Latin, English leans heavily on syntax, on a word order that tells you what role each word is playing. If I say, "She loves chocolates," you instantly recognize the sequence of Subject (She), Verb (loves), and Object (chocolate). Since most Latin words are inflected at the end, Latin syntax is far more variable, often setting words in what seems a crazily reverse order. When Virgil launches the Aeneid with "Arma virumque cano," the um in "virumque" tells you it's the object of "cano," I sing. So instead of SVO, it's actually OVS: "Arms and the man sing I." (The final o of cano means "I.")

Odd as that may sound in English, it tells you something about English syntax, which is far more pliable than most people realize. Now and then it's fun to see how far it can stretch. Though you can't say "The cow milked Ben" if Ben did the milking, you can say, "Arms and the man I sing," or even "Arms and the man sing I," or "Dancing she loved, jogging she hated." Why not? If you want to keep a reader awake, which is surely the minimum required of any good writer, you have to put a spring in your step now and then. You have to break the lock-step march of SVO syntax.

Just about the time I first met the eloquence of Cicero, I picked up a copy of what has long been the vade mecum of aspiring young writers: E.B. White's Elements of Style. Since my writing had become too hypotactic, with too many dependent clauses stacked under main ones, I was struck by the easy grace of White's own style, which tends to the paratactic: one main clause after another, with nothing but and between them. I also loved his command of metaphor, as in warning against such hackneyed adjectives as little,, very, and pretty. These, White wrote, "are the leeches in the pond of prose, sucking the blood of words." Who could resist such a blood-sucking picture?

Which doesn't mean, of course, that I never again used any of those leechy words, or always took his advice on other matters. One of his favorite maxims, which he credited to Wilfrid Strunk (co-author of the Elements) was "Omit needless words!" I thoroughly share his loathing for excess verbiage, which is the bane of much academic writing, but deciding just what to cut can be tricky. I could shorten that last sentence, for instance, by writing "deciding what to cut is tricky," but "just" sharpens the edge of my editorial knife and "can be" makes allowance for non-tricky cuts. For my money, there is no short cut to perfect prose, no simple rule that always applies. But White comes close when he argues that every word in a sentence should pay its way by telling us something we need to know and would otherwise miss.

OK, back to my last two years at BC High.

Besides learning how Cicero's Latin eloquence flayed Catiline in 63 BC, we also studied two great epics of classical literature in their original Latin and Greek: Virgil's Aeneid and--in my senior year--Homer's Iliad. If that sounds impressive, I must tell you something very strange: so far as I can recall, neither I nor anyone else in the class ever got all the way through these works--not even in translation. Instead we crawled just part way through them--like ants in a long deep trench. Assigned about twenty lines of the original for each class and given a hasty "pre-lecture" on them in English, we were told to work them up for the next class: ready not just to translate them but to pick them apart, to say exactly how their parts fit grammatically together. Years later, having read the whole of the Aeneid in Latin during my freshman year at Georgetown and having taught both the Iliad and the Odyssey to various students, I have come to know and love the shapes of their mighty narratives. But I don't for a moment regret my years in the trenches crawling from one line to the next. I know no better way of getting inside the texture of an ancient epic and hearing the timeless music of its tongue.

Looking back on my years at B C High, I now clearly see that the one thing sorely lacking among its students was ethnic diversity. Besides being all Roman Catholic, we were also all white—with the exception of just one kid named (I kid you not) Lou White! This left us not just totally oblivious of Black life but also perfectly free in our blissful ignorance to stage every year something mow recognized as grossly insulting to African Americans: a minstrel show.

In minstrel shows, which originated in America in the early nineteenth century, white performers typically blackened their faces so as to impersonate Blacks, whom they mockingly portrayed as dim-witted, superstitious, cowardly, lazy, buffoonish, or just plain stupid. Amazingly enough, neither any of us nor any of the Jesuit fathers who taught and supervised us during this period ever realized just how much our minstrel shows demeaned Blacks. So I must confess that for two years in a row, I blackened my face to play an "end man" in these shows, hopping around the stage, singing dumb ditties, and telling lame jokes in would-be Black dialect. Fortunately, however, the BC High minstrel show is now a thing of the long past.

In my senior year at B.C. High, our homeroom teacher was a frizzy-haired, slightly puckish taskmaster named Father Will Power. I did not impress him. Though he once remarked that some of his fellow Jesuits thought me "quite a boy," he did not, and he was always ready to pounce on any stupid point I might be tempted to make--as I often was. When he opened one afternoon class on poetry by inviting us to comment on Coleridge's "Kubla Khan," I put up my hand and blurted, "a lot of mixed metaphors here."

"Name six," came the reply.

And of course I couldn't name one.

Later on I realized that "Kubla Khan" does not mix metaphors. To report on the poem for a graduate seminar at Princeton taught by Professor Richard Blackmur, I dug deep into the structure of its imagery, which brilliantly deploys a pair of polarized symbols. Like Apollo hovering over Dionysius, I found, it sets the elegant order of the stately dome over the raging, turbulent river, deftly exemplifying the polar complexity of all great art, which shapes raw energy, encircles power, and thus gives it lasting form and life.

After making these points (which will hardly be news to anyone who knows the poem well), I did not expect a verdict from Professor Blackmur. A poet as well as a critic of breathtakingly wide range , he had so far never voiced a judgment on anyone's report--merely tugged one of its threads into a whole new web of his own wondrous weaving. But during his comments after my report, I clearly heard him say, "your report, which was very good. . . ." The sweetest relative clause I ever heard. Perhaps even Father Power might have approved.

Beyond learning from Father Power some things about classical and modern literature as well as about my own thoughtlessness, I did a few other things during these years. Since the Jesuits set great store by speaking as well as writing well, I not only joined the debate team but also practiced speech-making (having made my start with the "Call to Arms") and even entered a regional oratory contest--which I lost through thoughtless over-confidence.

Just too late for that contest, though, I discovered a speech that probably would have won it: the speech that Winston Churchill gave to the British Parliament after the Allied evacuation of Dunkirk in early June of 1940. When England stood all alone against the Nazis, against the mightiest and deadliest war machine ever assembled in the whole history of humankind, Churchill declared--in words I can recite from memory even now, almost 70 years after first memorizing them--

Even though large tracts of Europe and many old and famous states have fallen or may fall into the grip of the Gestapo and all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule, we shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end, we shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender,

Once I read these electrifying words, they drove all thought of Patrick Henry from my brain. No wonder Edward R. Murrow said that Churchill mobilized the English language and sent it into battle. Who could fail to be roused by such words?

Much later, while doing research for Politics and Literature at the Dawn of World War II, I discovered that not one of the writers I studied--not one who had been moved to write by the outbreak of World War II--felt anything like the spirit of heroic defiance voiced so eloquently here by Churchill. But all that was to come in my own continuing, lifelong education.

Meanwhile, back in high school, I had much to learn about my own defects. More than once, in fact, overlove of my own words led me astray. After joining Junior Achievement at the Boston YMCA, I was first appointed president of a little (!) company that made and sold metal brackets for plants, but was then booted out of office for spending too much time yacking with our grownup advisers (three executives from a factory in Jamaica Plain) and too little making brackets--or even trying to sell them.

But in December for two years running, I made about $70 (a small fortune!) selling around our Jamaica Plain neighborhood some Christmas wreaths that I bought in Haymarket Square and decorated myself with pinecones, berries, and big red ribbons. (Pricing note: while I charged $2.50 for small wreaths and $3.50 for big ones, my wife just paid twenty bucks (!) for the berried sprig of hemlock branches now hanging on our front door.)

And of course there were parties, girls, and the siren song of fifties fashions. In the spring of my junior year, I begged my ever-indulgent mother to buy me a white wool suit with jacket lapels so long they reached all the way down to a single button at the waist: a zoot suit! One look in the mirror made me think I was the living end. So I proudly wore it with a long red necktie (high there, Donald!) to every party and school record hop that came my way. But after just a few weeks I couldn't stand to look at it, and thus learned a hard lesson about the fickleness of my own taste.

I also remember my graduation from BC High in June of 1956, or rather one small piece of it.

Strangely enough, given my fascination with words, I cannot remember a single word of any speech delivered that evening at Symphony Hall in Boston, or even any of its ceremonies. What I do remember is the yellow dress worn by the lovely young lady who had miraculously consented to be my date for the dinner and dance held right after graduation at the Lenox Hotel. High-cheeked, bright-eyed, self-assertive, and bold in all the right ways, Nancy had already captivated me, and the result was the most enchanted evening I had ever had up to that point.

After the dance broke up, a classmate and friend named Fred Coffey treated several of us to drinks and more dancing at the Statler Hotel, where I first heard the famous tune from My Fair Lady (just opened on Broadway) that perfectly captured my mood: "I could have danced all night." Finally, en route back to Nancy's home in Charlestown, we stopped by Charles River Park. Sitting beside her in my mother's Ford convertible, with the top down and the car wide open to the moonlight and the heaventree of stars, I put my right arm around her neck and kissed her on the lips--our first.

To this very day, I can still remember exactly what I felt when, seconds after that kiss, the short stiff hairs of her left eyebrow grazed the edge of my lower lip. As a pair of good virginal Catholics, we stopped far short of Tom Wolfe's formula for modern courtship: "Their eyes met, their lips met, their bodies met, and then they were introduced." But that moonlit, starlit moment was as close as my seventeen year old self ever got to heaven,

Like most teenage crushes, this one soon expired, and a few years later I met another Nancy who became the love of my life--as explained further on.