CHAPTER FIVE

THE CRUCIFIXION OF POLAND

In the late morning of Monday, August 28, 1939, a young British journalist who had just been sent to Poland by the London Daily Telegraph caught a riveting prevision of war.

Though new to her job, the 26-year-old Claire Hollingworth was already primed to make the most of what she suddenly saw. Born outside the industrial city of Leicester and raised on a nearby farm, she had not only set out early on to make herself a writer but had also absorbed the history of war from the ground up—while taken by her father to see battlefield sites in Britain and France. She grew up determined to play her part, if only as an articulate witness, in the key events of her own time. Breaking her engagement to a perfectly eligible young man whose family was known to her own, she served as secretary to a League of Nations organizer, won a scholarship to the School of Slavonic and East European Studies in London, and then studied Croatian at Zagreb University. In late December of 1938, after the Germans had seized the Sudetenland of Czechoslovakia, she went to work for the British committee set up to aid its refugees. Dispatched to Katowice, in southwest Poland, she helped several thousand Czechs get British visas until July of 1939, when M15--the British Security Service--shut down her operation because she was thought to have signed visas for “undesirables” such as Communists and Jews. Back in London shortly afterwards, she reportedly “ran into” Arthur Wilson, editor of the Daily Telegraph, and talked him into sending her back to Poland as a stringer.

Knowing what was coming and where it was coming from, she lost no time in seeking it out. On August 26 she flew to Warsaw, where packs of foreign journalists were already trading gossip and rumors night after night with a dizzying assortment of military officers, diplomats, socialites, spies, mistresses, and prostitutes in the restaurant and bar of the Bristol hotel—the city’s grandest (Olson and Cloud 44). But Claire Hollingworth did not join them. Instead she dined at the Hotel Europejski with Hugh Carleton Green, formerly chief of the Telegraph’s Berlin bureau, who had been kicked out of Germany to Poland and was now Claire’s boss. She might have stayed in Warsaw reporting on its prewar fever: on the gas masks that had just been issued to its people, on the windows criss-crossed with masking tape, on the thousands of Varsovians—including opera singers, rabbis, clerks, and artists—who came out with picks and shovels when Mayor Starzyński called for volunteers to dig zig-zag trenches (Olson and Cloud 44). But leaving such stories to others, she and her new boss agreed that she should decamp for Katowice, which was not only the Polish city she knew best but also sat just eight miles from the German border along Poland’s southwest.

After taking the night train, she was invited to stay at the British consulate there, for she already knew the consul—John Anthony Thwaites—from her work with refugees. On the morning of August 28, she made a cheeky request: she asked to borrow the consulate’s limousine and driver. When she explained that she wanted to see what the Germans were doing on the other side of the border, Thwaites roared with laughter—and let her go.

With a Union Jack fluttering by its side, the car soon rolled past open-mouthed border guards at Beuthen (now Bytom), Poland. About half an hour later, as the limousine climbed a hill on the autobahn just past Gleiwitz, a snakeline of German motorcycle dispatch riders roared past. At the same time, a gust of wind lifted the sheets that had been draped beside the road. As if a pair of theater curtains had been drawn aside, the valley below suddenly appeared as a stage set for war: hundreds of tanks, armored cars, and field artillery from the 10th Army of Field Marshall Gerd von Rundstedt and its Panzer corps. The next day, August 29, the Daily Telegraph ran Hollingworth’s scoop anonymously on the front page: “1,000 Tanks Massed on Polish Frontier / Ten Divisions Reported Ready for Swift Stroke.” At dawn three days later, the swift stroke reached Hollingworth herself back at the consulate, where she was jolted awake by explosions and distant gunfire. Phoning the British Embassy in Warsaw and asking to speak with her friend Robin Hankey, the second secretary, she said simply, “Robin, the war’s begun.” When he asked if she were sure, she simply held the phone out the window so that he could hear the roar of tanks (Moore).

While Hollingworth managed to leave Katowice, keep just ahead of the invading Germans, and go on filing her stories, a 25-year-old Polish Cavalry officer named Jan Kozielewski—who soon after became Jan Karski-- was not so lucky. 1

At 5:00 AM on September 1, just before German bombs would cleave the clear and balmy skies over a Polish army camp near the factory town of Oświȩcim, about 22 miles south of Katowice, Jan rose from his cot. Exactly one week earlier, at 5:00 AM on August 24, he and thousands of other Polish reservists had been secretly mobilized: given just two hours to pack up and join their units for deployment against what seemed to be an imminent invasion of German troops.2 Posted to the 5th Regiment of Mounted Artillery, an elite unit serving in Poland’s first line of defense, Jan was a superlative specimen of Polish manhood—a natural aristocrat destined to excel. Born in the textile-making town of Łódź, about 80 miles southwest of Warsaw, he barely knew his father, who owned a small leather-goods factory and died when Jan was very young. As the youngest of eight children, he was raised by his mother Walentyna, who died when he was 21, and by his much older brother Marian, who funded his education. After primary and secondary schooling by Jesuits, who reinforced the devout Catholicism that he had already imbibed from his mother, he studied law and diplomacy at Jan Kazmierz University in the eastern Polish city of Lwów, where he won a speech-making contest in his final year. He then became the very model of a citizen soldier. After graduating first in his class of cadet Horse Artillery officers in 1936, he went on to gain a First in Grand Diplomatic Practice and then—as of January 1, 1939—to land a job that would normally have gone to someone much more experienced: administrative assistant to the Director of Personnel at the Polish Foreign Ministry.

When the mobilization order reached him at 5 AM on August 24, Jan was staying at the Warsaw apartment of his brother Marian, and he was supposed to reach the train station by 7:00 AM. But before doing so he felt that he had to see his boss at the Foreign Ministry--Tomir Drymmer. So there he waited for several hours in full military regalia: crisp khaki uniform, gleaming patent leather boots, and a polished leather belt from which hung his prize possession: the silver-handled sword he had personally received from Ignacy Mościcki, President of Poland, for being first in his class of Horse Artillery cadets. Yet when Drymmer finally showed up in the middle of the morning, he chuckled at Jan’s regalia. “You look like a clown,” he said.

Both men saw the coming invasion as nothing but a chance for the Polish army to show its stuff. When Jan apologized for the suddenness of his departure, Drymmer told him: “You will be back here in a couple of weeks. All this stuff with Hitler will take care of itself. We just need to show him that we are not Czechs.” Jan thought likewise. Unlike the Czechs, he knew, the Poles were determined to fight—just as an American journalist reported in the New York Times.3 Jan also knew that Poland’s armed forces were widely admired for their discipline and gallantry, and that its leaders—including Foreign Minister Jozef Beck, who had served in Jan’s own regiment—were confident of winning. He knew too that Poland had guarantees of support from Britain and France. He should also have known that Poland was not only surrounded on three sides by the Wermacht but also had to defend a border more than 1750 miles long, with no natural defense lines (Olson and Cloud 51). But whether or not this disquieting fact ever crossed his mind, there were many things that neither Jan nor anyone else in Poland knew about—or seriously thought about—in weighing its chances against a German attack.

First of all, in spite of the commitments they had made to Poland in May, the French had no intention of attacking Germany (with one slight exception) either on the ground or from the air. Nor did the British. Though Chamberlain had promised British support back in March, he had been told by his own chief of staffs that “Britain could offer no practicable help to Poland in the event of a German attack.”4 Compounding this defection, neither France nor Britain delivered any planes to Poland before the war even though the Polish government had bought 160 fighters from France and 100 Fairey Battle light bombers from Britain (Kochanski 53). Secondly, Poland’s own forces were dwarfed by Germany’s. On September 1, 1939, Poland had about a million men under arms with another million in reserve, and in the year leading up to September ’39, it had spent almost half its national budget on its armed forces—over a billion zloty.5 But that was about one tenth of what Germany had spent on its air force alone, and one fiftieth of its defense spending as a whole. As for ground forces, Poland’s 37 infantry divisions were just over a third of Germany’s one hundred (Kochanski 53, 55).

Besides this gigantic gap in military spending and strength, Poland was woefully under-prepared to fight a modern war. It had no heavy tanks at all—just over 300 medium and light tanks in the armored brigades and 500 “tankettes” attached to infantry divisions. Also, with only 6000 trucks in the whole country, half the number needed to transport its troops, the infantry still relied heavily on horse-drawn wagons—and horse-riding officers—as if still living in the nineteenth century. Even though Polish leaders had come to see that its battles could no longer be fought and won by cavalry charges, even though they knew that cavalry officers could hardly withstand an armored attack, they still made the cavalry part of the nation’s first line of defense and drew its officers from the aristocracy as well as—in Jan’s case—their very best men (Kochanski 53). Neither Jan nor his superiors knew how devastating modern weapons could be, or how fast the German Panzer tanks could move . Worst of all, the Polish air force lagged far behind the German Luftwaffe. Poland’s bombers flew faster than Germany’s and could carry heavier loads, and Poland’s capital was guarded by the five flying squadrons of the Warsaw Pursuit Brigade, two of them led by a 35-year-old nobleman named Zdislaw Krasnodȩbeski, who had been raised to join the cavalry (like Jan) but had instead become a pilot. Nevertheless, Poland had only about one seventh as many combat planes as Germany, and at an Air Force exercise in early August, the American journalist William Schirer found them “dreadfully obsolete.” By comparison, the German Messerschmidt fighters were ultramodern: faster, better armed, and capable of higher flight.6

Knowing nothing of these disparities, young Poles like Jan who answered the call of duty in the early morning of August 24 had no idea what lay ahead of them. But in retrospect, it is startling to learn that during the summer of 1939, one of the most popular novels in Poland was Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind, the 1000-page epic of how the American South was devastated by the Civil War. Mitchell’s novel particularly struck a Polish writer named Rulka Langer, who thought of it as she watched her children playing at the family’s country house during what turned out to be the last summer of peace. Looking back at this time through the lens of war, she wrote of Gone with the Wind, “Somehow I considered it prophetic” (Olson and Cloud 39).

Off across the Atlantic, in Culver City, California, movie makers had been looking at war through lenses of their own. In late June of 1939, after six months of work, they had finished shooting Gone with the Wind in Technicolor. Starring Clark Gable and Vivian Leigh and produced by David O. Selznick for $4.25 million (chump change now, but more than four times the cost of the average feature at that time), its script had been wholly re-written in February at the insistence of Victor Fleming, whom Selznick had hired after sacking the original director, George Cukor. In the ensuing months he also replaced the cinematographer and several other technicians, bitterly antagonized both Gable and Leigh (Leigh and Fleming also hated each other), and by his dictatorial meddling had driven Fleming to walk off the set for sixteen days. But Fleming returned in mid-June to shoot the film’s biggest scene: 800 injured soldiers writhing on the ground at the Atlanta railroad depot as Scarlet O’Hara weaves her way frantically through them. On September 9, when the film was first previewed at the Fox Theatre in Riverside, California, the audience loved it. Probably none of them knew that even as its scenes of fiery devastation flickered before them on the silver screen, cities and railroad depots all over Poland were actually being pulverized and incinerated.

On August 24, no one in Poland itself foresaw this devastation. Braced with confidence, Jan Karski got to the mobbed railroad station in the center of Warsaw and boarded a train headed toward Krakow. “Just in case” the war should last longer than two weeks, as his brother’s wife warned him, he was carrying a duffle bag stuffed with winter clothes plus a Leica camera which-- he jokingly told himself --might be used to snap photos of defeated German generals. As the train chugged south, he caught a disturbing omen at each station: hordes of weeping women on the platform bidding farewell to their husbands and sons. But once he joined his unit, Jan found his fellow officers sharing his optimism: all the Poles had to do was show Hitler they could fight.

Hitler could hardly wait. On the night of August 24, Jan’s very first night in his barracks, southwest Poland became a hot spot. With Czechoslovakia now under German control, Poland had to defend itself against Slovak as well as German troops, and after crossing the Slovak border into southern Poland about 42 miles south of Krakow, both sets of troops attacked the Jablonka railway tunnel in the Carpathians. Though the Poles repelled this attack, it was only the first of many overtures to the full-scale assault on September 1.

The Germans’ first target that day was Danzig-- in the northwest. At 4:45 AM the German battleship Schleswig-Holstein opened fire at the small Polish military depot on the Westerplatte in Danzig harbor, where a group of fewer than 200 soldiers would hold out for seven days. At the same time (on September 1), the German SS attacked the Polish post office in Danzig. When the postal workers refused to come out and took refuge in the basement, the Germans poured gas into the building, set it alight, and gunned down the workers as they rushed out to surrender (Kochanski 59). On the night of September 7, however, shortly after the Westerplatte soldiers surrendered, the Poles took their revenge. As the Nazis celebrated their success with a parade on Danzig’s Adolf-Hitlerstrasse, a single Polish hydroplane dropped six bombs on them (Jackson 55).

But the Germans dropped far more. Back in southwest Poland, in the army barracks near Oświȩcim, Lieutenant Kozielewski rose at 5:00 AM on September 1, as already noted. Expecting yet another uneventful day, he stooped over to peer into the bathroom mirror and carefully shaved a face still carbuncled by some adolescent acne. At 5:05, almost before he could have finished shaving, two massive explosions shook the camp, and for the next three hours a herd of Panzer tanks rolled in to pulverize the ruins. Altogether, the invaders wrought such death, destruction, and havoc as to make resistance impossible. Though Jan and a few other officers remained miraculously unhurt, the uncontrollable state of the horses left the Polish soldiers no way of hauling artillery against the invader, especially since the Luftwaffe kept raining incendiary bombs on the camp (Wood 5-6, Karski, SS 6).

Elsewhere in Poland, the cavalry was likewise overwhelmed. During battles fought in the village of Mokra near Jan’s hometown of Łódź and in Pomorze, north of Warsaw, Polish horsemen actually charged and routed German infantry. But when the Germans counter-attacked with machine guns, artillery, armored cars, and tanks, they cut down the cavalry in minutes (Kochanski 63). Altogether Poland was struck from three directions—the northwest, south, and southwest—and indiscriminately bombed. On the first day the Luftwaffe struck a hospital, a school, churches, and shops in the farming town of Wiehun near Łódź, killing over 1600 people—10 percent of the population. Given Hitler’s command to annihilate the Poles, the Luftwaffe bombed railways, towns, ambulances clearly marked with red crosses, ambulance trains, and passenger trains. On the ground, fleeing passengers were machine-gunned. During all of September, the hundred miles of road leading west from Warsaw displayed mounds of rotting cadavers—mostly those of women and children (Kochanski 62).

The capital itself was bravely defended by the Warsaw Pursuit Brigade. Facing a tidal wave of eighty German bombers and fighters, four fighter squadrons of the brigade did all they could to check it, soaring above the bombers so as to dive down upon them or even attacking them head on with guns blazing. As a result, the Poles downed six bombers while losing just three fighters. But Germany still had nearly 1400 planes in Poland, and its fighters quickly overwhelmed the Poles. In five days, the Warsaw Brigade downed 34 German warplanes and damaged 29 more. But the brigade also lost two thirds of its own planes—36 in all. As Poland grew ever more devastated, the mood of its frustrated fighter pilots was surely encapsulated by Miroslaw Ferić, whose P-11 had been shot down by a Messerschmidt 110 on the third day of combat and who had barely survived his parachute landing. Still nursing his wounds two days later, Ferić wrote in his diary: “The lovely Polish autumn [is] coming Damn and blast its loveliness” (Olson and Cloud 52-53).

Jan Karski would have grimly agreed. With the German Fourteenth Army pounding away at the artillery batteries of the Polish Army of Krakow—including Jan’s cavalry regiment—Jan and his fellow officers organized their men for withdrawal to the local railroad station. But as they marched through the town of Oświȩcim, which was heavily occupied by Volksdeutsche (Poles of German descent, the Nazi Fifth Column), the Polish troops were fired on from houses and buildings. Though the officers kept their men from setting fire to the town in retaliation, Jan never forgot the last thing he saw as the train pulled out of the station: “the treacherous windows of Oświȩcim” (Karski SS 7), a town whose Germanized name would later be used for the nearby concentration camp known as Auschwitz.

Crawling east through the night at what must have been no more than walking speed, the train did not even make the forty miles to Krakow by dawn. It was then an easy target for a group of German Henkel 111 bombers that smashed and strafed the boxcars for over an hour, leaving hundreds of men dead and dying amid the smoking wreckage. Miraculously, Jan’s boxcar was unhit. But all that he and the other survivors could do was leave the mess behind, walking east and picking up other soldiers just as dazed as they were. Their plight typified that of the Polish army as a whole. In the north, where two regiments of the Army of Pomorze had been obliterated by the Luftwaffe while being driven from the corridor, so few soldiers remained alive that “in reality the . . . Regiments had ceased to exist” (Kochanski 64). Likewise, Jan wrote later, the Army of Krakow—his own army-- had become “no longer an army, a detachment, or a battery, but individuals wandering collectively toward some wholly indefinite goal” (Karski, SS 7).

But the Army of Krakow was not yet finished. Though the armies of Lodz and Pomorze started retreating on September 2, the Army of Krakow managed both to defend Krakow itself and to keep the Germans from breaching its line to Army Karpaty in the east (Kochanski 64). Furthermore, on September 3, crowds gathered in Warsaw were mightily cheered by the news that Britain and France had both declared war on Germany: news that left Berlin crowds stunned into silence, as William Schirer observed. But when Warsaw got the news, a band played the anthems of all three allies—Britain, France, and Poland—and flags of each soon decorated the streets (Kochanski 65). Two days later, on September 5, the Poles themselves showed what they could do against the German 1st Panzer division in the battle of Piotrkow, fought between Lodz and Krakow in the southwest. Losing just two tanks of its own, the Polish 2nd Light Tank Battalion demolished 17 German tanks, two self-propelled guns, and 14 armored cars. But the Poles still lost the battle because they scarcely knew how to use their armor and capitalize on their success. They also found that rivers could no longer protect them against German armor—especially when the heat of summer had largely turned the rivers into dry beds. After the armies responsible for defending western Poland were ordered to move east on September 5, across the Vistula and Dunajec rivers in central Poland, German tanks and artillery could easily ford them (Kochanski 65-66).

The Saar Offensive and the Joke War

In the face of German bombs, tanks, and machine guns, the Poles had strong moral support. In parliament on September 3, the day Britain and France both declared war on Germany, Arthur Greenwood—Deputy Leader of the Labour Party—greeted Poland “as a comrade whom we shall not desert. To her we say, ’Our hearts are with you, and, with our hearts, all our power, until the angel of peace returns to our midst” (qtd. Kochanski 64). But just what did these stirring words mean? What would Britain actually do for Poland? And what would France do? The less than stirring answers came soon.

On September 4, France finally ratified its military convention with Poland, which—as noted above in Chapter 4-- bound the French to do three things if Germany attacked Poland: 1) strike Germany from the air; 2) launch a diversionary offensive into German territory on the third day of French mobilization, which had been fully declared on September 1; and 3) throw the full weight of its armies into the war no later than fifteen days afterwards. Yet as also noted above in Chapter 4, General Gamelin—who signed the military convention with Poland—never intended to keep his commitments, and the British did nothing to stiffen his spine.

At a meeting of the British war committee on September 4 in London, the newly reinstated First Lord of the Admiralty—Winston Churchill—suggested that the Royal Air Force should support the next French attack on Germany’s Siegfried Line, or Westwall, as the Germans called it.7 The very next day, in a message sent to Edward Raczyński, Polish Ambassador to the United Kingdom, the Polish Air Force appealed “to the Command of the Royal Air Force for immediate action by British bombers against German aerodromes and industrial areas within the range of the Royal Air Force, in order to relieve the situation in Poland” (Kochanski 68). But Sir Cyril Newall, Chief of the RAF, argued that aerial intervention could only retard the delivery of German reinforcements, and in any case the French government would not authorize the bombing of Germany—by the RAF or its own planes-- for fear of retaliation against Paris.8

As a result, even as German Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers relentlessly struck Poland, the British and French would do nothing to Germany from the air, and the Saar Offensive was strictly a ground operation launched from northeast France. On the night of September 7, six days after French mobilization, General Gamelin sent a few light French reconnaissance units into German territory along a 15-mile front southeast of Saarbrucken. Two days later, he sent heavy infantry and mechanized forces from the Fourth and Fifth Armies while also ordering units from the Third Army into the Warndt (Wendt) Forest, which makes a bulge in the French border just west of Saarbricken. But Gamelin threw against Germany far less than the full weight of French forces, as he had promised the Poles. With 85 divisions plus 2300 tanks available on France’s northeast frontier, he could easily have overwhelmed the 23 German divisions facing them under German First Army Commander General Erwin von Witzleben, especially since Germany had sent all its tanks to Poland and the heavily armored French Char B tanks could easily withstand the Germans’ anti-tank shells. But Gamelin did nothing to exploit these advantages. He dispatched no more than fifteen divisions—and perhaps as few as nine.9

By September 12, the French Second Army had captured 20 deserted German villages and pushed five miles into German territory. On the surface, the Germans seemed pushovers. Rather than fighting the French in most villages, they posted signs—presumably in French-- saying that they had no quarrel with French soldiers. But they also mined fields, booby-trapped doors, and hid explosives under Nazi signs. And the slightest sign of real resistance gave the French pause. In one village, a single German machine gunner stopped the French advance for more than a day (Austra).

The Saar Offensive was little more than a timid feint. Rather than meeting their commitments to Poland by fiercely attacking Germany from the west, Britain and France together strove to provoke the Germans as little as possible. Though the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) landed in France on September 7, the same day that French soldiers marched into the Saar, the British never joined the Saar Offensive, and though Churchill proposed to float mines down the Rhine River, the French objected that Germany might retaliate by bombing the bridges over the Seine. Likewise, when a British MP proposed bombing the Black Forest to ignite uncontrollable fires in Germany, the Air Minister—Sir Kingsley Wood—overruled the suggestion on grounds that such fires would damage private property (Austra). It is startling to compare this punctilio with the ruthlessness of German attacks on Poland, as Jozef Beck explained to both the French and British ambassadors in Warsaw on September 2. The Luftwaffe, Beck told them, could throw all of their weight on Poland, and besides striking military targets, they were also bombing non-military factories, villages far from military targets, and large numbers of civilians.10 In spite of this information, which both the French and the British had by September 3, when they declared war on Germany, French Prime Minister Daladier not only kept the French Air Force out of Germany but also asked the British RAF not to bomb it (Austra).

On September 21, four days after Soviet troops invaded Poland from the east, Gamelin halted the Saar offensive short of the Westwall and secretly ordered that in case of a German counterattack, French troops should return to the Maginot Line. In other words, rather than pushing his troops onward toward the Rhine (which they might well have reached in two weeks), Gamelin feared that Germany would now move many of its own troops back from the east to the west. He therefore turned his offensive into a defensive crouch—all the while telling a purely fictitious story to the Poles.11 On September 30, he ordered General André-Gaston Prételat—head of the French Second Army—to withdraw his troops in secret by night. By mid-October, Germany had 70 divisions along its western border—quite enough for Witzleben’s First Army to counterattack the remaining French troops and, on October 24, cross the border into France itself. Occupying a sliver of French territory, Germany thus anticipated its conquest of France in May of the following year (Austra, Swick 1141). Furthermore, while the French lost some 2000 men to illness, wounds, or death (mostly from mines and booby traps), the Germans lost only about a third of that number.

For all the inoffensiveness of the Saar Offensive, however, the paralysis of the British and French in this period was perhaps best exemplified by a meeting between Chamberlain and Daladier that took place on September 12 in the town of Abbeville, which straddles the River Somme—here shrunk to a canal-- about 12 miles from the coast of Picardy in northwest France. The Somme has given its name to one of the bloodiest battles of the First World War. Sixty miles upriver from Abbeville, the Battle of the Somme killed over 19,000 British soldiers on its very first day--July 1, 1916--and by the time it ended in the following November, it took about 420,000 British casualties, plus about 200,000 French. Ironically enough, the British prime minister was invited to fish in the Somme during his visit to Abbeville. Whether or not he did, could he have failed to remember the river of British blood forever attached to its name?12

Chamberlain says nothing about this battle in his own account of the meeting--the first meeting of the Anglo-French Supreme War Council. It was held in France because Chamberlain felt that meeting Daladier in his own country would be a “mildly spectacular move on my part,” and it was held in Abbeville because—as Chamberlain himself records-- the British Air Ministry thought flying to Paris would be too risky: “Above the clouds, they said, the French would probably shoot me down. If below, I should almost certainly fly into a hill” (Self, NCDL 1: 445, 447). Reaching the Abbeville Aerodrome after a bumpy morning flight, he and Lord Alfred Chatfield, Minister for Coordination of Defense, were met by the commanding general of the district and—with the landing of another plane soon after—by Daladier, General Gamelin, and various other French officials. Driving together to the sub-prefecture of Abbeville (essentially a town office), they started talking at once, with Chamberlain taking the lead “as the French,” he noted afterwards, “did not seem to have any points of their own.” Chamberlain thought it all went swimmingly: “the most satisfactory conference I have ever attended. There was no point on which there was any disagreement between us and when we parted we felt both of us fresh hope and confidence” (Self, NCLD 1: 448). Their hope and confidence seems to have sprung from the simple fact that they agreed on every point. But what they agreed upon was to do nothing for Poland.

To be sure, France had just been trying help Poland by invading the Saar and thus trying to harass Germany on its western front. But so far as the record shows, the Saar Offensive was not even mentioned at Abbeville—perhaps because it had largely run out of steam by the time Chamberlain met Daladier there. Poland itself was a topic they finessed. Though both men knew very well what German bombs and guns were doing to Poland, and though they had both pledged to support it in case of German attack, they quickly agreed to do nothing. Two days before the conference, Chamberlain had coolly noted that “Poland is being rolled up much faster than our people had anticipated” (NCDL 4: 445). Now he simply wrote Poland off. “There’s nothing to do from a material point of view,” he told Daladier, “to save it. The only way of doing so is to win the war.” Daladier feebly raised the possibility of opening up an eastern front by sending supplies through Romania, and thereby encouraging the Polish resistance. But the only thing actually sent to the Poles at this time was a telegram from Gamelin to Marshall Rydz-Smigly, commander of the Polish army, gamely suggesting that Polish soldiers remaining in the country might wage guerilla warfare against the Nazi occupation (Paillat, 2 GI 198). Having left Warsaw on September 7, however, the Polish Marshall was already headed east toward Romania, which would shortly serve not as a conduit for war supplies but rather as a refuge for him and his staff as well as for Polish president Ignacy Mościcki and Colonel Jozef Beck, Poland’s Foreign Minister (Kochanski 72, 78-79).

What then could France and England do? Thrusting the short-term fate of Poland brusquely aside, the two prime ministers turned to what must have seemed a much more urgent question: the vulnerability of their own cities. Their strategy, insofar as it could be called that, was simply to avoid provoking their enemies—or potential foes. Italy, they agreed, must be given every reason to stay neutral, and since Germany had so far dropped no bombs on France or England, it must be given no reason to do so—especially because the Luftwaffe could do much more damage to the concentrated factories of France and England than allied bombing could do to the dispersed factories of Germany. Also, Chamberlain said, it would be very awkward to strike civilian structures under the pretext of targeting military sites, “above all with respect to the opinion of the U.S.”13

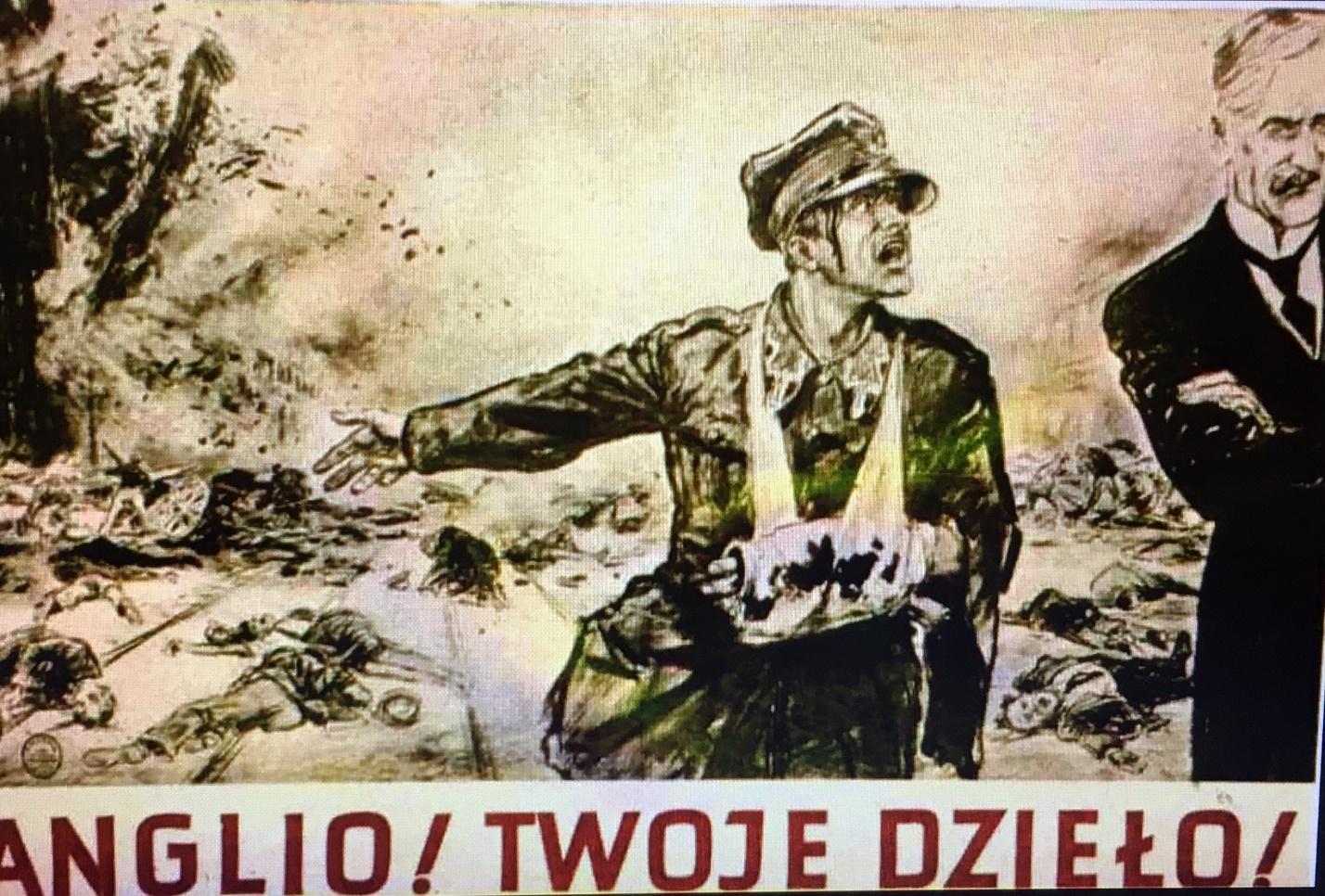

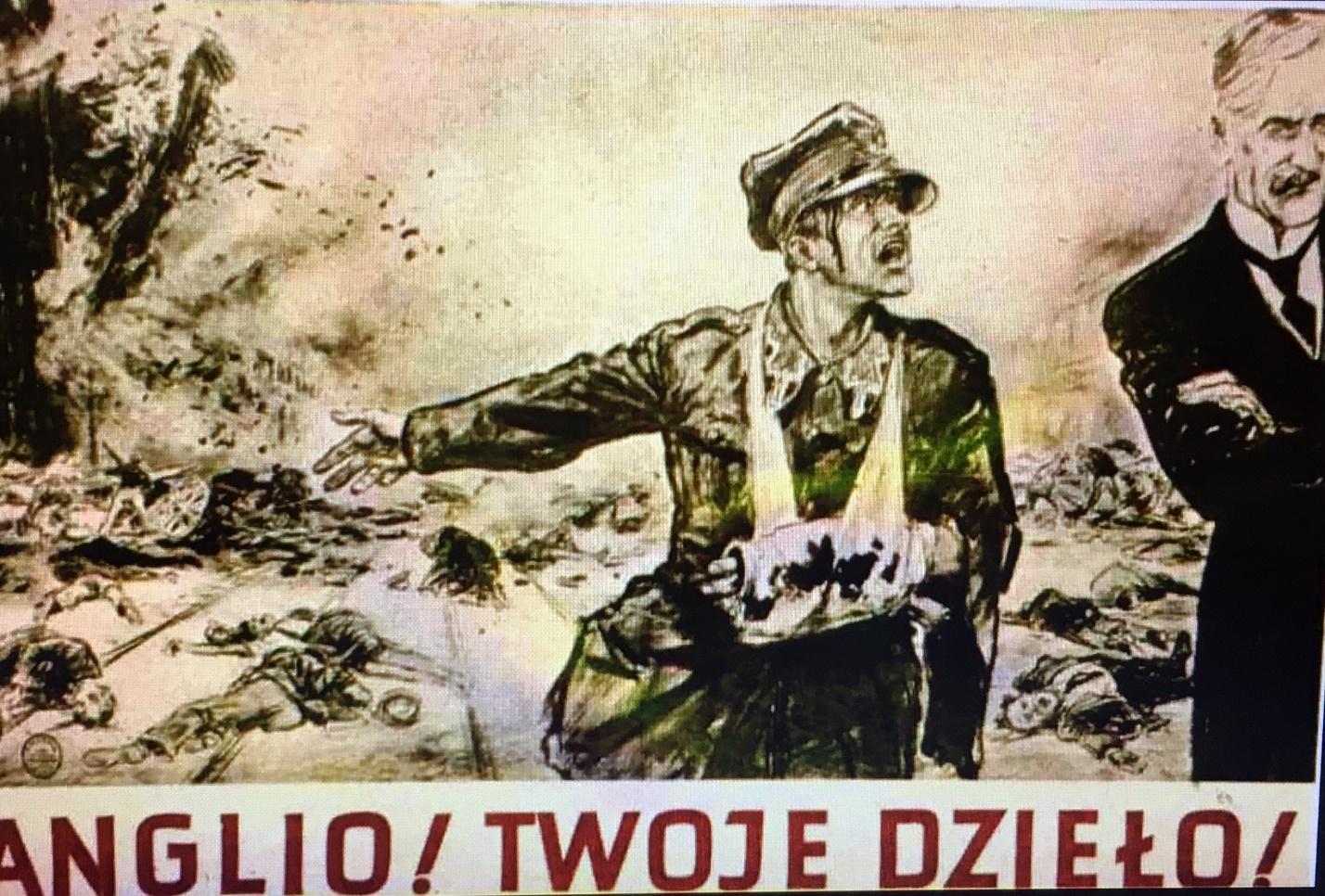

Besides the danger of ruffling public opinion abroad, then, both men worried far more about ruffling the feathers of the German eagle than about doing anything effective on behalf of Poland. And Chamberlain was almost equally vexed about a French move in the Middle East, where General Maxime Weyand, Commander in Chief of French troops in the Levant, was visiting Ankara in hopes of persuading Turkey to join the alliance against Germany. Instead of welcoming this move, Chamberlain saw it as evidence that France sought to challenge British influence in the Middle East, so his own ruffled feathers had to be smoothed by Gamelin (Paillat, 2 GI 199). In the end, except for savoring the good news that the allies would soon be able to circumvent America’s neutrality laws so as to buy planes, as noted in Chapter 4, the British and French ministers decided to rest on their hands. “Our interest,” said Daladier simply, “is to wait” (Paillat, 2 GI 38). Thus began the drôle de guerre, the funny war, the phony war, the joke war: the cruelest possible joke on Polish expectations, as exemplified by this Polish poster of a wounded soldier gesturing to a corpse-strewn battlefield as Chamberlain stands by with arms folded:

ENGLISHMAN! YOUR WORK!

While Chamberlain took great satisfaction from the work done at Abbeville, Daladier felt exactly the opposite. According to William Bullitt, the American ambassador, who met him in Paris right after the conference, Daladier thought Chamberlain “a broken man.” Whether or not he knew that the British prime minister was already suffering from the cancer that would end his life in fourteen months, Daladier found him not only sunk in “decrepitude” but also shockingly indifferent to the bombing of Poland and just as shockingly opposed to using the bombardiers of the Royal Air Force against military sites in Germany (Paillat, 2 GI 201). Yet Daladier’s own Air Minister, Guy La Chambre, judged the RAF hardly better equipped to strike Germany than the French were. Even though he had just assured Daladier--on August 22--that the state of French aviation was no cause for concern (see above, chapter 4), La Chambre now knew that in a matter of hours, the Luftwaffe had destroyed 90% of the Polish Air Force. Given that fact, La Chambre feared it would be many months before either the French Air Force or the RAF could offer much help (Paillat 2 GI 201n27).

Hard as he was on Chamberlain after the conference at Abbeville, Daladier was even harder on himself. To Bullitt he confessed that his political career and probably his life itself could not last “three months.” Though it would be just over six months before Paul Reynaud would replace him (in March of 1940), Daladier saw nothing but disaster ahead. Once Poland is conquered, he said, Hitler would use the whole Luftwaffe against France, and its bombs would strike the nation so brutally that Daladier would be blamed for the shortage of French planes—whether or not it would prove to be his fault (Paillait, 2 GI 201-202). In any case, the waiting game that Daladier and Chamberlain so calmly agreed to play could hardly be a winning game. In a note sent to Daladier on September 13, the day after the Abbeville conference, Gamelin explained the price of delay. If France and Britain wait until spring to act, he wrote, Hitler will have time to reconstitute his divisions—around 200 in all-- from the Polish campaign, and France will have only about 70—plus some “barely trained” English divisions. In short, he wrote, “time here works against us!” (Paillat 2 GI 203n32).

Poland and the Ordeal of Jan Karski

Time surely worked against the Poles. As Daladier and Chamberlain opted “to wait” (for a miracle, perhaps?), the Luftwaffe continued its relentless bombing of Poland, and Lieutenant Jan Karski slowly made his way eastward along with a shell-shocked horde of survivors—soldiers and civilians alike. “We found the highways jammed with hundreds of thousands of refugees,” he wrote, “soldiers looking for their commands, and others just drifting with the tide” (Karski, SS 7). The only thing they knew about the war was that Nazi troops were advancing from the west. None of them knew that the Non-Aggression treaty just signed by Germany and the Soviet Union included a secret protocol; none of them knew that since the two countries had agreed to carve up Poland, Soviet troops would shortly invade from the east, catching the Poles in a vice.14 For the first half of September, then, the only thing that Jan and his fellow refugees could imagine doing was to keep shuffling eastward, sleeping in barns, scrounging for food, doing everything they could to keep ahead of the Germans.

Besides turning food into a precious commodity, the war suddenly wiped out the value of Jan’s most precious possession. When his military rations ran low after a few days, he traded his new Leica for a bag full of bread and cured meats. But after more than a week, when he decided to sacrifice his silver-handled sword for more provisions, he discovered that it was worse than useless—even for barter. From Jan’s point of view it was priceless: a gift from the president of Poland to recognize his stellar performance as a cavalry cadet. “It’s quite valuable,” Jan told a country storekeeper, and might have “historical significance.” But the storekeeper wouldn’t touch it. “You’re crazy,” he said. “Get that piece of shit out of here, before it brings misfortune on both of us.” The sword was no longer a sign of distinction, a token of Jan’s excellence in cavalry school. Instead it simply marked him as a member of the ruling class—a prime target of the invaders. No more an asset, it had suddenly become a dangerous liability. So Jan left the store with it, took a few steps, flung it into a field, and walked on (Wood 7).

Bad news now followed them, Jan writes, “like vultures feeding on the remnants of our confidence” (Karski SS 8). Besides seeing what German bombs had done to their country, besides finding towns, cities, villages, and railroad junctions turned into smoking ruins, they heard the names of Polish cities now occupied by German troops: Poznan, Kielce, Jan’s native city of Łódź, and Krakow--where Jan and his fellow officers had spent a couple of happy evenings less than two weeks before.

By September 18, as Jan approached the city of Tarnopol in southeast Poland, the Red Army had begun to occupy all of eastern Poland, offering what it called its “brotherly help” with merciless brutality. “In one town,” we are told, Soviet soldiers “dragged a Polish general from his car and killed him before the eyes of his wife; in another they disarmed 30 policemen and then executed them; in still another town they shot 130 schoolboys and cadets” (Wood 13). Two more vividly detailed accounts of their atrocities have been left us by two Polish women who were each just 14 years old when the Red Army arrived.

One was Danuta Mączka, who lived with her parents, three siblings, and a grandmother in a big brick house on a farm that was part of the Krechowiecka Settlement (“Osada”) near Równe, about 60 miles northeast of Warsaw. The settlement had been established by volunteer soldiers of the first World War on land given to them by the Polish government in 1920, after the territory had been won from Russia. Long after the ordeal of 1939, after living in England for more than forty years and consulting a diary that she had begun to keep (like a Polish Anne Frank) at the time of the invasion, Danuta recorded what happened starting September 17. While the Polish army was off fighting the Germans, she wrote, “the Soviet Army entered the Eastern Borderland of the Polish Republic under the false pretence of helping Poland in her fight against Germany.” On the same day she saw Russian tanks rolling through the Settlement, and Russian police promptly arrested leading Polish citizens. “During the following days,” she wrote, “Polish soldiers and even whole regiments were transported by train and put into labour camps in Siberia and other parts of the Soviet Union.” With the whole county of Wolyn (to which Równe belonged) made part of Ukraine, a newly formed Ukrainian Committee expelled from their properties all of the Polish soldiers who had settled there after the first war. From this moment, she recalls, “my happy childhood on the Krechowiecka Settlement ended.” Fearful, confused, and feeling deserted by Polish Officials (who had in fact been arrested and imprisoned), the settlers were at first assured by the Soviets that they would not be thrown out of their houses or driven from their farms. But this was a hollow promise. In just over a month, Danuta’s family and about a dozen others would be forced to leave their homes with just a few possessions—in what proved merely a prelude to deportation. After spending not quite four months in a rented apartment in the nearby Polish town of Tuczyn, they were dispatched to Siberia by sledge and freezing cattle cars along with hundreds of others. There they were kept in work camps until December 1941, when—after being attacked by Germany—Russia proclaimed an amnesty to all Poles living in its territories.15

Still more painful was the ordeal of another 14-year-old girl who witnessed the Soviet invasion some 250 miles from Danuta’s settlement—in the northeast corner of Poland. On September 17, Elizabeth Piekarski was living on a family estate near the medieval city of Wilno (formerly Vilnius), which the Poles had wrested from Lithuania in 1920 and which Lithuanian troops backed by Germany and Soviet Union recaptured—after four days of fighting-- on September 23. Awakened on the 17th by the loud droning of heavy planes, Elizabeth and her nine-year-old sister soon heard explosions and then saw smoke and flames rising over the nearby city. The Germans, they shortly learned, had first bombed a bridge over the Neman River and then incinerated a wooden factory standing next to it, killing 68 people from Elizabeth’s village alone. A little later in the day, Russians came to their house, arrested their father, and took him away. Then about 20 Polish Communists who had come from somewhere outside the village starting killing. Armed but dressed in plainclothes, they made Elizabeth and her sister watch as they shot to death 42 people from the neighborhood—including two Orthodox priests--just outside the family estate, and then dug a hole for the bodies. To frighten the girls, the killers said, “Now it’s your turn,” and stood them against the wall. Though that was sadistic make-believe, the men took all they could from the estate, where her father had been breeding riding horses for the Polish army—for cavalry officers such as Jan. After killing all the pigs, they took away the few horses they found (some had just been sent off to the army and struck by bombs en route), killed all the pigs, seized many goods, and moved on to the next house.

Since Elizabeth’s mother was staying at a neighbor’s house and the frightened servants had run away, the two young girls were now alone and terrified in the family house. When their mother returned, she immediately set out to find their father, who was being held prisoner in the village school. Though his Communist guards fed him nothing, they let the girls bring him food, and though only jam and preserves remained in the family house, the girls managed to kill a chicken for him, and during the night some of the villagers brought food to them. But they lived in constant fear, with Communists threatening to kill them and calling them krovososy—Russian for “bloodsuckers,” a word Jan Karski would soon hear often flung at anyone who looked like an officer. Sheer terror struck down one of their neighbors—a friend of their father’s with a lovely estate about 10 miles away. When he heard that the Russians were coming, he burned his whole farm, shot his favorite dog and then killed himself-- because he knew what awaited him.

Worse still, Elizabeth learned that her father had been taken away to some unknown location, and her mother resolved to track him down. So leaving behind her sister, whose weak lungs were not up for any journey, Elizabeth and her mother spent a long day tramping from one place to another asking for news of her father. When they returned to the house that night, they found it a wreck, with all the doors and windows broken and no sign of Elizabeth’s sister—until they finally spotted her crouching behind a piano in one of the big rooms. The girls had often been told that the ghost of their grandmother haunted that room, so Elizabeth asked her sister if she was afraid of the ghost. “No,” she said, “I’m afraid of the people”—meaning the Polish Communists who had vandalized the house and taken what remained of its valuables. The next day Russian soldiers arrived. Though they did no more damage and complained of what the Polish Communists had done, their words were hardly consoling. “Never mind,” they said, “we’ll take you to Russia and teach you our ways.”

They were taught to suffer. Within a month the family estate was turned into a collective farm. Though they were allowed to live on it for a time, Elizabeth’s father was soon deported to Minsk, where—as they learned much later—he was shot before the end of the year. In the following March his wife and daughters were deported to Kazakhstan, where they were made to work in brickworks, road-building, and collective farms as the mental health of Elizabeth’s mother slowly disintegrated and many other Polish deportees died of such things as heat stroke. Like Danuta, Elizabeth herself was freed in 1941 and travelled to Pahlevi in Persia (now Iran), where she was aided by the British Army. But her mother and sister did not leave Russia until 1945.

The Capture of Jan Karski

With the obvious exception of the Communists who vandalized Elizabeth’s house, every Pole who witnessed the Soviet invasion could tell his or her own story of shock, anguish, and misery. But Karski’s is above all a story of perseverance. On the morning of September 18, the day after the Russian invasion began, he was approaching Tarnopol (now Ternopil, Ukraine), a small but proudly multicultural city in southeast Poland. He had been marching for fifteen days. Averaging about 20 miles a day since leaving Krakow, he had covered about 300 miles. Though he was now walking with a group of medical officers whom he had met while getting a bandage for his blistered heel, his “ridiculous patent-leather shoes”—as he later called them--were so badly worn that he had to walk beside the road, which the broiling sun had turned into a gridiron. Suddenly he and his fellow officers caught a piece of news that someone had picked up from a radio: the Russians had crossed the border. From somewhere inside Poland, they learned, a long stream of announcements broadcast in Polish and Ukrainian as well as in Russian had been telling the Poles that the Russian soldiers had come not as enemies but liberators—“to protect the Ukrainian and White Ruthenian population” (Karski, SS 9). In fact the Red Army had been secretly ordered to “destroy the Polish Army” and annihilate the Polish state even while pledging to free their Slavic “brothers”--the Ukrainian and Belarussian populations-- “from the yoke of Polish capitalists and nobility.” They also pledged to free Polish soldiers from their bloodsucking officers (such as Jan himself) who were said to be part of the nobility (Wood 368-69n5). Though Jan knew none of this yet, the word “protect” made him and the other officers nervous. They knew very well that Spain, Austria, and Czechoslovakia were now “protected” by the Nazis. “From whom,” they wondered, “were we to be protected? Were the Russians going to fight the Germans . . . ?” Since no one could answer these questions, they decided to press on toward Tarnopol, about ten miles off. The prospect of learning something definite put even a little spring into their weary steps (Karski, SS 9).

The spring soon turned to wintry gloom. After rounding a bend about two miles outside the city, they found a horde of refugees standing far ahead of them on an otherwise deserted stretch of road, with a long file of military tanks and trucks behind them and a stream of unintelligible words flowing from an unseen loudspeaker. On barely making out the sign of a hammer and sickle painted in red on one of the military vehicles, they realized that what they were hearing were Polish words spoken with the sing-song intonation of a Russian speaker. Soon after, another voice amplified by a megaphone on one of the Soviet tanks identified itself as that of a commander. Assuring everyone that they had nothing to fear (“We are Slavs like yourselves, not Germans, We are not your enemies”), the commander asked to speak with some officers. The confused hubbub that followed turned to fearful silence when a Polish captain finally emerged from the mob of soldiers, waved a dirty handkerchief over his head, walked gingerly toward the Soviet tanks, politely met a Red Army officer, and walked off with him toward the tank holding the commander. After fifteen minutes of agonizing suspense, Jan heard yet another voice speaking through the megaphone of the commander’s tank, but this time it was the voice of the Polish captain delivering “grave news.” Announcing the end of the Polish High Command and of the Polish Government as well, he ordered all the Polish soldiers around him to join the Soviet forces—specifically to join the commander’s detachment “immediately, after surrendering our arms.”

The paralyzed silence that greeted these words was broken only by a desperate sobbing that came from somewhere in front of Jan and then turned into hysterical speech. In the final moments of his life, the speaker—who turned out to be a non-commissioned Polish officer-- had just realized exactly what the Russians and the Germans were now doing to his country. “Brothers,” he shouted, suddenly reclaiming the true meaning of the word, “this is the fourth partition of Poland. May God have mercy on me.” He then blew his brains out (Karski SS 12-13).

The pandemonium ignited by this act was soon quelled by the sing-song voice of the Russian commander speaking Polish once more through his megaphone. With just one exception, he ordered the soldiers to surrender every weapon they had—machine guns, rifles, hand weapons, bayonets and belts—by leaving them in front of a white hut standing on the left side of the road. The one exception—“Officers may retain their swords”—was of course useless to Jan, since he had already thrown his away (Karski SS 13).

Short of suicide, the Poles had no choice but to comply. With two colonels taking the lead by dropping their revolvers in the doorway of the hut, other officers followed one by one as their men looked on in disbelief. “I took my turn,” writes Karski, “as if hypnotized, unable to convince myself that all this was really happening.” Unlike everything else about him, his barely used revolver was “still sleek and smart-looking” as he dropped it on the pile of weapons. He and his fellow soldiers were now utterly defenceless. Told to line up in good order facing Tarnopol, they were flanked on either side by Soviets bearing light machine guns, and before as well as behind the marching Poles rumbled tanks whose guns all pointed straight at them. The Poles had not been released from bloodsucking nobles, nor liberated by their Slavic “brothers.” In Jan’s own words, they were now simply “prisoners of the Red Army” (Karski SS 13-14).

As more than two thousand Polish soldiers made their way at dusk to the Tarnopol railroad station with machine guns pointed at them every step of the way, Jan first began to think of escape. Though Soviet guards walked beside them as they marched about ten abreast in ragged lines, the guards were spaced about five lines apart, and since the streets were flanked by crowds of civilians, one Polish soldier at the edge of a line just ahead of Jan—who watched with a thrill of amazement--managed to disappear into the crowd. But Jan’s line had a guard at the end of it who seemed be looking—or rather glaring—only at Jan. So Jan felt he had no chance. As his line neared the railroad station, all he could do was emulate the charity of some of the onlookers—“the good people of Tarnopol” so different from the treacherous Volksdeutsche of Oświȩcim. Moved by the kindness of a woman who audaciously handed a coat to one of the soldiers, he covertly tossed into the crowd his wallet (containing his money and papers) and a gold watch that his father had given him. Keeping only some of his money, a ring, and a gold medallion, he entered a station that was stinking and crowded with men sprawled everywhere, sat down on the floor, and fell asleep.

Two or three hours later, he awoke feeling “utterly wretched” both physically and mentally, but still managed to catch a conversation among three Polish officers discussing the war. While one of them—a lieutenant—calmly declared that the Polish Army had been wiped out by German planes and tanks, the other two held out hope of successful resistance, and Jan silently sided with them. “The whole Polish Army smashed in less than three weeks!” he told himself. “It was fantastic” (Karski SS 18)—clearly meaning impossible.

Yet it was nearly true. Though Polish forces still held Warsaw, the capital was under siege and many other cities in western Poland were now occupied by German troops, as Jan had already learned. Furthermore, the Polish government had left the country. On September 17, the day before Jan became a prisoner of the Red Army, the president of Poland had slipped across the border to Romania along with the Commander of the Polish army, Marshall Rydz-Smigly, and Colonel Jozef Beck, the Foreign Minister.16 Three days later, in a final broadcast to his Polish troops, the Commander effectively ceded the eastern half of Poland to the Soviet invaders. Since most of the Polish Army was fighting the Germans, he said, we must “avoid pointless bloodshed by fighting the Bolsheviks.” Withdrawing as many troops as possible to Rumania and Hungary, and thence to France, he aimed to form a new Polish army there (Kochanski 79).

Within days of the Jan’s capture, therefore, Soviet troops occupied the eastern half of Poland with no virtually no resistance from Polish troops—let alone their allies.17 By September 18 the city of Lwów, about 80 miles northwest of Tarnopol—the city where Jan had spent his university years—had been under siege for a week by the German 1st Mountain Division and about to be caught in the same vice of partition that had closed upon Jan. On September 20, just after the Polish commander of Lwów had rejected a German demand for surrender, the Germans ceased firing because the Red Army had entered the city—whereupon the Poles surrendered it to the Soviets, who they believed were allies. Two days later, the northern fortress of Brest was directly transferred to the Soviets by the Germans who had besieged it: with the Poles ready to surrender and the Red Army set to advance, the general of a panzer division handed the fortress to a Soviet Colonel of the Red Army (Kochanski 75-76).

Meanwhile, in the west, Warsaw had become the first European capital to be devastated from the air. To smash its resistance before sending in ground troops, the Germans had been bombing it for more than a week, and by September 25 the onslaught of bombs and artillery had ignited 200 fires, crippled the city’s waterworks, knocked out its power station, and killed about 40,000 civilians. Two days later the city was surrendered by General Tadeusz Kutrzeba, and on September 30, 140,000 Polish troops marched out of Warsaw into captivity (Kochanski 62, 81-82). But the Germans did not immediately arrest Stefan Starzyński, the mayor of Warsaw, who had done all he could throughout the bombing to keep alive the spirit of what he called –in a radio broadcast-- “wonderful, indestructible, great, fighting Warsaw in all its glory” (Kochanski 81). The mayor’s right hand man (as well as longtime friend) was Jan’s older brother Marian, who had been Chief of Police in the capital since 1934 and who had helped the mayor to organize the Civil Guard, created on September 6. On September 28, the day after Warsaw surrendered, Mayor Starzyński awarded Marian his third Medal of Valor, and since the Germans asked him to keep the city functioning as before, he decided not only to keep his job but to urge the police to go on doing theirs—while secretly doing all they could to resist the occupation (Karski GPP 368n2, Wood 25). Starzyński was soon arrested by the Gestapo and probably killed at Dachau (Kochanski 83). But Marian remained Chief of Police until May 7, 1940, when he was seized by the Gestapo in the dark early hours of the morning and in mid-August sent to Auschwitz, built on the site of the army camp where Jan had first felt the shock of German bombs.18

The whole conquest of Poland had been personally supervised by Adolph Hitler. Starting on September 4, when he was driven in a six-wheeled Mercedes to Plytnica in northwest Poland, he visited the frontline nine times—always with the rest of his staff and escort trailing in identical cars. On 22 and 25 September he joined German troops massed in the suburbs of Warsaw, where he watched the relentless shelling of the city through a large periscope. On October 5, after Poland was wholly defeated with over 150,000 of its citizens killed (Piotrowski 301), he returned to a shattered Warsaw for a grand triumphal parade up the Aleje Ujazdowski, the city’s most beautiful boulevard, where he and his henchmen stood on a podium facing the American Embassy. On this very day in America itself, a large cartoon on the front page of the Chicago Tribune hailed the “Isolation” of Uncle Sam as “the Envy of the World,” and a big black headline at the top of the page-- “VANDENBERG: SELL NO ARMS!” -- summed up what a leading Republican Senator had said about the new Neutrality Bill, which FDR strongly backed because it would allow fighting nations to buy American war materials. The bill passed anyway in early November, but it could do nothing for Poland—let alone for the young Polish lieutenant who had just walked into the arms of the Soviets.

Turning back to the morning of September 19 at the Tarnopol railroad station, Jan and his fellow soldiers woke up to the chugging arrival of a long chain of cattle cars. With no formalities such as identity checks, the Russian guards herded the Poles onto the train—sixty in each car. Jan later learned that as more Polish prisoners arrived while all this was happening, many men took advantage of the confusion by slipping out of the station and melting into the local population. But for now, Jan remained among the prisoners. Told to stock up on water from the station faucets, they were each given a pound of dried fish and a pound and a half of bread and packed into a nearly lightless box that was shut with the slamming of doors and the clang of an iron bar that bolted them in. Since Jan’s car was among the first of more than sixty, he had to sit for two hours waiting for the others to be filled (Karski, SS 18-19, Wood 14).

With just fifteen minutes a day for fresh air and a chance to shake out his aching limbs, Jan spent four days and four nights sitting or lying in the jammed car as it rattled slowly northward. On the cold nights of late September, he and the others got a little warmth from the iron stove in the middle of the car (tending it was their only relief from the monotony of the ride) and they each got a daily ration of black bread and salted fish. But all the light they had came from a narrow ventilation slit on top of the walls and a hole in one corner of the floor that served as a toilet. Only when they stepped out of the train on the second day and heard the local population speaking did they realize that they had crossed into Russia, though it was actually a Russian-speaking part of Ukraine. In the ensuing weeks, more than a quarter of a million Polish soldiers and officers would be thus transported—in many cases never to return (Karski, SS 19, Wood 14).

At one of their daily stops, the prisoners in Jan’s car were touched to be offered water and cigarettes—a precious commodity. But one Polish officer got a rude awakening when he thanked a Russian woman—in Russian—for a tin of water and then eagerly tried to claim kinship with her and the others. “You are our friends,” he said. “Together we will fight and defeat the German barbarians.” Backing away and stiffening, she sneered at him. “You!” she said. “You Polish, fascist lords! Here in Russia you will learn how to work” rather than “oppress the poor.” Suddenly Jan saw himself and his fellow officers through Communist eyes. Just as his prize silver sword had suddenly become worse than worthless—a sign of hated aristocratic status—officership itself was here and now in Russia despised. Presumably, a Russian offer was a champion of the people. But a Polish officer could be nothing but a bloodsucking fascist lord-- unworthy of even the pretense of brotherly friendship.

On September 24, having covered a little over four hundred miles in five days since leaving Tarnopol, the train of prisoners stopped at the village of Kozel’shchina in central Ukraine—a village so small that it had no railroad station, only a platform and a few small houses. Shivering, coughing, and sneezing in summer uniforms that were no match for an icy wind, the Poles were ordered to march for several hours, mostly uphill over bleak terrain, while Jan could think of nothing but escape—and returning to his native land. Bitterly he recalled his last, festive night as a civilian--the night before he was mobilized. His parched throat made him long for the cool wine he had drunk at the Portugese Legation ball as well for as the music and of course the lovely young women.

After passing through a forest to a broad plain partly defined by dense forest, the men were led single file into the prison camp, one of 140 that the Russians had prepared for their Polish prisoners. It was a cluster of stone buildings, wooden shacks, and ten huge wooden barns encircled by a barbed-wire fence with a watchtower standing at each corner. As officers and enlisted men were sent to their respective quarters, Jan was once more made to realize that by Communist standards, his rank was a liability rather than an asset. While ordinary soldiers were lodged in the stone buildings of what had once been a monastery and a church, Jan and most other officers were packed into huge wooden barns that had been turned into barracks (with 400 men to each barn), and policemen as well as reserve officers who had ranked high in civilian life had to build their own wooden huts in the yard of the former monastery. Doctors were stuck in a pig shed. The message implied by this inverted system of housing was made plain on the very first day by the camp commander, who told all the officers that they were “exploiters and bloodsuckers” and that they would have to earn their keep by working just as hard as enlisted men (Karski, SS 21-22, Wood 15-16).

Demeaning as it was, Jan quickly grasped the rules of this new order. Just as he had earlier thrown away his prize silver sword, he now carefully disposed of his diplomatic passport during the first two nights by shredding bits of it into the various latrines around the camp. He also tackled willingly the hardest and grimiest jobs: not just chopping wood in the forest, as all the officers were made to do, but volunteering to clean the huge kettles used to cook their food. Besides drawing a “queer satisfaction” from doing these jobs, he gained a precious dividend from the second one: with the scraps he pried from the sides of the kettles, he got more food than any other prisoner (Karski, SS 22, Wood 16-17).

But no food could assuage his hunger to escape, or at least get out of the Soviet Union. Believing (as most educated Poles did) that Russia was a land of barbarians, and knowing that Polish prisoners of Tsarist Russia had been dispatched to Siberian oblivion, he calculated that he would do better in the hands of the Germans. After weighing every possible means of escape and finding none of them practical (the trains were too well guarded and the country too unfriendly), he learned from a young fellow officer that the Russians and the Germans had agreed to swap prisoners ranking no higher than private. By what Karski thought was a provision of the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact of August 23, the Germans would hand over to Russia all Ukrainians and Byelorussians, and in return, the Russians would release to Germany all Poles who were ethnically German or who had been born in Polish territories now occupied by German troops.19 This arrangement seemed to legitimize the claim that each side made to its half of Poland, with “German” Poles sent west and “Russian” Poles sent east. But Jan cared nothing for geo-politics in this case. All he cared about was meeting the requirements for transfer. Though his diplomatic passport was gone, he still had—tucked into his cap—a birth certificate showing that he came from Lodz, now occupied by the Germans.

One big question remained. As Jan put it to the young lieutenant who had told him about the prisoner swap, how could he pass himself off as a private while wearing the uniform and patent-leather boots of an officer? The lieutenant had an answer: trade the uniform and boots for those of a private who either can’t or doesn’t want to be exchanged. Jan could do it while both he and the private were out chopping wood in the forest, and then Jan could go back to the private’s barrack, where the Russian guards knew men only by numbers.

Miraculously, the plan worked. After getting to know a Ukrainian peasant of private rank named Paradysz, Jan managed to meet him behind a large tree standing some hundred yards from the nearest guard. There Jan traded his shirt, jacket, and boots for the uniform and shoes of the private, who simply ripped off Jan’s insignia and buried it under a rock. (Luckily, though patent-leather boots should have made the guards suspicious, Paradysz was not afraid of being thought an officer himself because he had the papers to prove himself a private. ) That evening, Jan quietly joined a group of privates as they entered the onetime church that was now their barracks, and the Ukrainian slipped in through an unguarded window in the back. Unquestioned by his new mates, who had already been briefed about him, Jan thus became a private.20

Early in the morning of the next day, which would have been about November 6, he asked to see the camp’s commander. Speaking broken Russian, he posed not only as a private but as a one-time laborer—a house-painter who had born in Lodz and thereby qualified for transfer back to German-occupied territory. He also claimed that he wished to rejoin his wife, who (he said) was pregnant with their first child. Whether or not the commander swallowed this bit of sentimental fiction, Jan could prove his birthplace by means of a birth certificate, and that was enough to secure his release. On the next day, therefore, six weeks after he had reached the camp, he joined two thousand other Polish soldiers who were sent to the Germans in exchange for about that many Ukrainian and Byelorussian prisoners. If Jan had not contrived to fake his way out of the Kozel’shchina camp, he would shortly after have been sent to another Russian camp and then—in April or May of 1940—he would have been executed by pistol shot at the edge of a pit in Kalinin, Kharkov, or the Katyn Forest: the fate of some 22,000 other Polish officers and leading citizens (Karski SS 26, Wood 19).

Instead he was sent back to the German half of Poland. Retracing the miles he had covered enroute to the prison camp in the Ukraine, Jan and two thousand other Polish soldiers were shipped in boxcars to the town of Przemysl, which straddles the river San about 60 miles west of Lvov. At dawn on a cold, windy, drizzling day in early November—probably about the 6th--the shivering, raggedly dressed Poles were lined up in a muddy field on the outskirts of the historic city center on the southeast bank of the San, which now belonged to the Soviet half of Poland. A few miles away, across the bridge leading to the northwest bank, were the crisply uniformed officers of the German army, which now occupied western Poland.21

Since the Poles had to wait in the field for five hours, and since the the Russian soldiers not only allowed the prisoners to step out of formation but also talked with them, Jan moved around, doing his best to learn what lay ahead for the Poles. With his broken Russian all he could learn is that life would be worse under the Germans—that the Poles would have to work very hard (Karski, SS 28).

He had of course no way of learning what Hitler was planning. Flush with the quick conquest of Poland, the Fuhrer was determined to strike in the west—specifically in France—on November 12. But on the 6th, General Walther von Reichenau was doing all he could to forestall this attack, or at least postpone it. Though the general was absolutely loyal to Hitler, he hoped the British could be persuaded to do something to check the Fuhrer’s bellicose plans, so he sent a message to Britain by way of Hans Robinsohn, a German-Jewish businessman who had emigrated to Denmark in 1939 and remained a leading member of the German Resistance (Klemperer 159-60).

By November 9, when the message reached London, Hitler had just survived a much more dramatic plot to check his designs on the west. On the evening of November 8, Hitler had returned as usual to the great hall of the Burgerbraukeller in Munich, where every year he addressed the Old Fighters who had helped him sieze power in the Beer Hall Putsch of 1933. Knowing not only when Hitler was coming but exactly where he would speak, a carpenter with Communist leanings named Johann Georg Elser hid out every night for a month inside the Beer Hall after it closed—so that he could chisel out a hole in one of its pillars and pack it with a time bomb. But the diabolical luck with which Hitler had already survived more than 25 attempts on his life saved it again on November 8. Though the bomb dutifully exploded, killing 8 and injuring 57, Hitler was unharmed—because he ended his speech and left the building about 10 minutes before he had been expected to do so. The only good thing to come out of the botched attempt was that the attack on the west was pushed to November 19, and then repeatedly postponed until Germany invaded France on May 10, 1940.22

At midday on or about November 6, shortly before Hitler was nearly obliterated in Munich, Jan and his fellow prisoners were marched two or three miles from the field where they had waited all morning to a muddy river crossed by a bridge. On the other side stood a mirror image of their motley, ragged selves—a horde of Ukrainians and Byelorussians headed for the Soviet side. They were guarded by German officers who had come to exchange them for Poles. Neither set of prisoners knew exactly whether to scorn or envy the other, but since every one of the prisoners had chosen to be transferred, each felt the need to assert the rightness of his choice. As a group of men from the German side passed a group of Poles headed the other way, a big Ukrainian shouted, “Look at the fools; they don’t know what they are letting themselves in for.” To which one of the Poles shot back, “We know what we are doing. We don’t envy you either” (Karski, SS 30-31).

But none of the Poles knew what lay ahead. After reaching the far side of the bridge, where they were promptly grouped in formation, they were told that they would be well treated, fed, and given work. But on marching to the train station, they were each granted only “a split second” to drink from the well and store up on water, and once packed onto the train—sixty men to a boxcar, as before—they were each given just one half a loaf of black bread and a bit of artificial honey for a journey of 48 hours. It was hardly an auspicious introduction to life under German rule.

Life got only worse when they reached the town of Radom, about 60 miles south of Warsaw. Though Jan—like most of the others--had succumbed to the wishful expectation that they would eventually be freed, his first sight of the distribution camp on the outskirts of town shook this belief. It was a huge, dismal expanse surrounded by barbed-wire fences. Once massed in the center of the camp, they were told that they would ultimately be released and put to work. But they were also told that any infraction of camp rules would be swiftly and severely punished, and also that anyone who tried to escape would be shot (Karski, SS 31-32). Paradoxically, this speech stiffened Jan’s determination to escape as soon as he could--even while crushing his hope of escaping from this particular camp during the ten days he spent there.

Life in the camp was so bad that Jan must have sometimes wondered if the burly Ukrainian had been right after all. The food was a cruel joke: two servings a day of revolting, watery slop plus barely more than half an ounce of stale bread. The prisoners slept on hard, bare ground thinly strewn with filthy straw under the roof of a building that looked more like a ruin than a military barracks. They were given nothing to protect them from the damp November cold—no coats or blankets—and no medical treatment for the colds and other diseases that sometimes ended their lives. Day after day, they were also made to endure what Jan had never seen before: abuse relentlessly prompted by a sheer love of brutality. Besides always addressing the prisoners as “Polish swine,” the guards seized every possible chance to kick them in the stomach or smash their faces, and Jan himself saw at least six men shot for trying to climb the barbed wire--or just for looking as if they had been trying.

Elsewhere in Europe, the Germans were just as vigilant with two officers of the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) who likewise tried something objectionable. On November 9 in the Dutch town of Venlo on the German border, Major Richard H. Stevens and Captain Sigismund Payne Best had expected to meet representatives of the German Resistance. But since the German SS had already penetrated the British SIS, and since Hitler felt sure that the SIS had a hand in the attempt to blow him up in Munich, he ordered the kidnapping of the two British agents, who were kept in German custody until the end of the war. The whole episode thus dealt a major blow to British hopes of negotiating an alternative to war (Klemperer 161-62).

Having jettisoned his own hope of escaping from the distribution camp, Jan nonetheless took comfort from two sources. One was the company of three privates he had come to know on the train to Radom, especially a peasant named Franek whose gaiety and warmth proved irrepressible. With them Jan shared such things as socks, leggings, and money, and since Franek had a shaving kit, he managed to give Jan what was probably his first shave since the fateful morning of September 1—more than two months past. Since Jan’s face was not only dirty and bearded but also hyper-sensitive and pockmarked with acne, the operation took nearly an hour and felt like torture. But it was just one of the things the men did for each other, which included the collection of their daily food rations and of paper-wrapped bundles thrown at various times over the barbed-wire fence.

That was the other prime source of comfort. Six years before Americans began sending CARE packages to Europe, some unseen hand or hands from the town of Radom covertly delivered packages of food, clothing, and medicine to Polish prisoners: mostly bread and fruit but occasionally a priceless pair of old shoes or a bit of money. One day Jan found and brought back to his new friends a bundle containing a bottle of something that stank. But when Franek joyfully recognized it as a medicine for lice and scabies, he carefully divided it among the four so that they could use it on their lice-ridden bodies, hair, and clothes. The relief was worth the stink.

Yet even more important than food, clothing, and medicine was a crucial piece of advice that Jan found early one morning. The day before, he had scrawled an urgent request on a piece of paper torn from one of the packages: “Could you supply civilian clothing? Four of us here will risk anything to escape.” At dawn the next day, he found a package containing a note as well as food: “Cannot supply clothing because I would be seen. You are leaving the camp in a few days for forced labor. Try to escape when you are on your way.” This advice may well have saved Jan’s life. When he shared it with the other three, they all decided that their best chance of escape lay with the train ride (Karski, SS 35).

Five days later, on or about November 16, Jan and all the other “Polish swine” who had come from the east were prodded with rifle butts onto a long train, with each group of 60 or 65 packed into a car that looked and smelled if it had been used for shipping cattle. Measuring about 50 feet by 10 feet by 8 feet high, Jan’s car let in light only through the door and through four small windows set at eye level. After being packed in with a tub of water to share and small portions of dried bread, they were told—once again—that they would eventually be freed. But once again they were also told that they would be shot if they tried to escape. Shortly after, the door was slammed shut and the familiar clang of an iron bar locked them in. With just fifteen minutes of outdoor exercise every six hours, they began a hot, stinking ride on a train that mostly crawled and often stopped.