Francesco Trevisani, Banquet of Marc Antony and Cleopatra (1717), Oil on canvas. detail

Joshua Reynolds, Kitty Fisher as "Cleopatra" Dissolving the Pearl (1759). Oil on canvas. Kenwood House.

SERVING TWO MASTERS: PORTRAITURE AND HISTORY IN THE DISCOURSES AND ART OF SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS

Paper presented at Sir Joshua Reynolds: What's New?

Colloquium sponsored by Université de Lausanne / Musée d'art et d'histoire de Genève and organized by Jan Blanc (Université de Genève) et Pascal Griener (Université de Neuchâtel). 16-18 September 2010.

James A. W. Heffernan

Joshua Reynolds combined extraordinary ambition with remarkable humility. Just before the end of his very last discourse, where he salutes Michelangelo as the epitome of the great style that he urges young painters to cultivate, Reynolds admits that he has not done so himself. As an admirer rather than an imitator of Michelangelo, he says, "I have taken another course, one more suited to my abilities, and to the taste of the times in which I live" (D 282). He thus admits that his own practice has swerved from his precepts: rather than taking the high road to great style, he has trod what he had long before defined as the low road of portraiture. For even though he has ranked History Painting far above portraiture, even though he has privileged the idealized and generalized depiction of human action , he has practiced an art that aims to produce simply the "likeness" of an individual face and form: an art that cannot equal history painting because its subject is "a particular man, and consequently a defective model" (D 4, 60, 70).

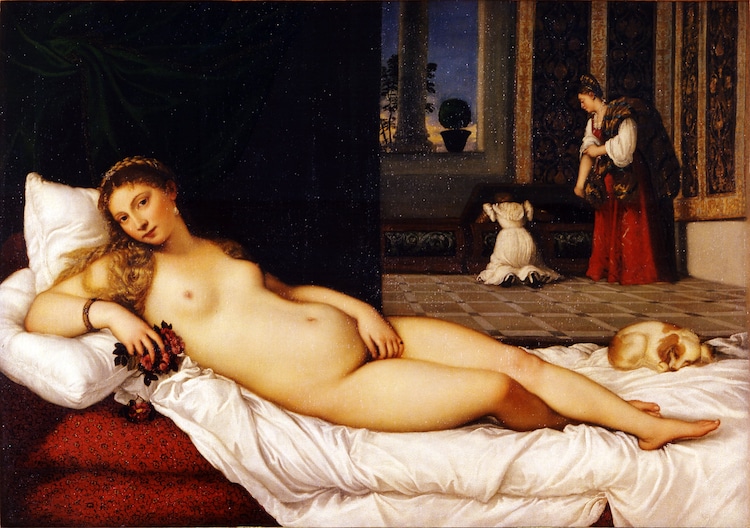

To this withering case that Sir Joshua seems to make against his own achievement in art one might quickly respond in a number of ways. First of all, besides the more than two thousand portraits that he painted in a staggeringly productive career of some forty years, he also produced a number of works that unequivocally qualify as history paintings in the eighteenth-century sense, such as the Virgilian Death of Dido (1781) and the Shakespearean Death of Cardinal Beaufort (1789). Furthermore, Martin Postle justly observes that "the borderline between history painting and portraiture was uncertain during Reynolds' lifetime" (Postle 1)--partly because of Reynolds' own practice. Straddling the line between portraiture and history is the portrait of impersonation, where a recognizably contemporary face is said to represent a categorically "historical" figure who is sometimes mythological or allegorical. In Kitty Fisher, a London courtesan whose face was well known from prints appears as Cleopatra dissolving a pearl in a goblet of wine--in a pose copied from a painting by Francesco Trevisani:

Francesco Trevisani, Banquet of Marc Antony and Cleopatra (1717), Oil on canvas. detail

Joshua Reynolds, Kitty Fisher as "Cleopatra" Dissolving the Pearl (1759). Oil on canvas. Kenwood House.

Likewise, Reynolds copies a pose from Michaelangelo's Leda and the Swan to portray an actress now identified simply as Miss Morris—a friend of Reynolds, Johnson, and their circle—as the allegorical figure of Hope Nursing Love (1769):

Michelangelo, Leda and the Swan (1530). Copy attributed to Rosso Fiorentino. London, National Gallery.

Joshua Reynolds, Hope Nursing Love (c.1769). Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery: Port Eliot Collection

Reynolds also cast Emily Warren--another well-known London prostitute—as Thais, the incendiary mistress of Alexander the Great:

Joshua Reynolds, Thais (1781). Oil on canvas. Waddesdon Manor.

Paintings like these suggest that for Reynolds, portraiture was not simply a detour from the high road of history painting. Rather than swerving from that road, he tried to set his portraits right on it--thus serving two masters at once.

Beyond these borderline portraits, portraits masquerading as history paintings, Reynolds himself argued that portraiture could at least aspire to the level of history. In his Fourth Discourse, he modestly classifies himself as one of those who move "in the humbler walks of the profession" (D 70) but also ventures to say that such painters may borrow certain features of the grand style. Thus, he says, a portrait-painter may "raise and improve his subject . . . by approaching it to a general idea," excluding "all the minute breaks and peculiarities in the face" and "chang[ing] the dress from a temporary fashion to one more permanent" (D 72). Whether or not Reynolds idealized his portraits by such means, Martin Postle tells us that by the mid-70s he was celebrated for historical portraiture, and that by the late seventies he "had established a reputation as a history painter, quite apart from his work as a portraitist" (Postle 42).

To consider one of Reynolds' history paintings from this period, however, is to wonder just how far Reynolds could transcend the particularities of portraiture even when his subject was categorically historical. Consider his Nativity, which was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1779 but survives only in engravings:

Joshua Reynolds, The Nativity (1779). Engraved by Samuel William Reynolds.

At lower right, Joseph appears as a wizened old man who could be recognized as the portrait of a beggar named George White, for Reynolds had already used him as the model for the starving Ugolino in a Dantean history painting of 1773:

Joshua Reynolds, Ugolino (1773). Detail.

Though there is ample precedent for using recognizable faces in history paintings, at least one reviewer of the RA exhibition found the historical impact of The Nativity enervated by its portraiture. Reynolds' virgin, wrote the reviewer, "a fine blooming young lady, about seventeen, seems very ill matched with poor Joseph, who, by way of contrast, appears to be above eighty, and extremely ugly: upon a nearer view, Joseph is our old acquaintance Count Hugolino, who was starved with his children in a former exhibition, but with less aggravated features, and in better care" (qtd. Postle 43). Even allowing for exaggeration driven by the journalistic impulse to spring a little joke at Reynolds' expense, this particular history painting makes us wonder just how well Reynolds could reconcile his ambition to paint history with his habit of producing likenesses.

Reynolds himself acknowledged the conflict between the two in Discourse IV. Even while explaining how the portraitist might borrow from the great style of history by erasing the minute particularities of a face and clothing the subject in something more permanent than a passing fashion, Reynolds admits that painters cannot make these moves without sacrificing similitude. If, he says, the painter seeks only to achieve an "exact resemblance" of an individual, he is likely "to lose more than he gains by the acquired dignity taken from general nature. It is very difficult to ennoble the character of a countenance but at the expense of the likeness, which is what is most generally required by such as sit to the painter" (D 72).

Reynolds himself thus prompts us to ask just how far he could meld portraiture with history. If he assiduously cultivated what Richard Wendorf has called "the art of pleasing," and if in his portrait-painting he had always to consider the wishes of his patrons, did they not impede or at the very least inhibit his ambition to achieve in portraiture something like the great style of history painting? Some scholars say absolutely not. They applaud Reynolds precisely for spurning the counsel of his friend Samuel Johnson, who thought portrait painters should avoid turning their subjects into heroes and goddesses, should eschew "airy fiction" for the sake of "diffusing friendship, and renewing tenderness" with recognizable features. Reynolds thought otherwise. According to Nicholas Penny, his "great achievement" was to make "his portraits heroic and poetic. To demonstrate his genius he was obliged to discover genius in his sitters—or to endow them with it" (Penny 17). Likewise, Martin Postle affirms that Reynolds frequently conveys "a heroicized image where the 'idea' not only transcend[s] but supersede[s] the individual's identity" (Postle 1). In Reynolds' own time, an unnamed contributor to the London Chronicle of May 1774 included Reynolds' portraits in an essay on history painting—and explained why. "While some artists," he concluded, “paint only to this age and this nation, [Reynolds] paints to all ages and nations, and we may justly say with the Artist of old, in aeternitatem pingo" (qtd. Postle 23).

We might question this grandiloquent claim on the grounds laid out by John Barrell. In his later Discourses, Barrell argues, Reynolds veers away from defining an art based on the timeless uniformity of human nature and "begins to advocate an art which would address itself to a national community, a nation state, different in character from other states" (Barrell 71). Nevertheless, since the author of the Chronicle essay takes most of his wording from Reynolds' own Discourse III, we do well to consider that discourse for its extensive definition of the great style--especially since Reynolds' criteria for this style remained essentially unchanged throughout the Discourses. Only in light of these criteria, I think, can we test the claim that Reynolds achieves in his portraits what he calls the great style, or in other words that he can serve at once the two masters of portraiture and history.

Before closely examining Discourse 3, however, we must recognize a point that Reynolds clarifies only much later: the great style is detachable from historical subject matter. In Discourse 13, he cites Jan Steen's Sacrifice of Iphigenia (1671) to show that a categorically historical subject can be treated in a "ridiculous" way:

Jan Steen, The Sacrifice of Iphigenia (1671). Oil on canvas. Leiden collection.

Here, says Reynolds, "the countenances are so familiar, and consequently so vulgar, and the whole accompanied by such finery of silks and velvet," that one might suspect the painter of aiming "to burlesque his subject" (D 236). A great subject, in other words, does not guarantee a great style. And if an historical subject can be painted without great style, great style can be defined independently of historical subject matter, which is essentially what Reynolds does in Discourse 3.

More than in any other discourse, Reynolds aims to show in this one why painting deserves to be called a Liberal Art rather than a mechanical trade, and to rank "as a sister of poetry." Pedagogically, he aims to show what aspiring painters must to do to make their own work achieve this status. To cultivate a great style, thry must address the mind and imagination of the spectator rather than simply deceiving the eye with "mere imitation" of the external world--precisely, of course, the trick for which Plato disparaged painters and poets alike. Unlike Plato, however, Reynolds urges painters to seek "ideal perfection and beauty" not in heaven but on earth--by deriving what he calls the "central form" from close study particular objects and figures. The great style thus transcends "all singular forms, local customs, particularities, and details of every kind" (D 44). Furthermore, says Reynolds, "however the mechanic and ornamental arts may sacrifice to fashion, she must be entirely excluded from the Art of Painting. . . . [The painter] must disregard all local and temporary ornaments, and look only on those general habits which are every where and always the same." In so doing, "he calls upon posterity to be his spectators, and says with Zeuxis, in aeternitatem pingo" (D 48-49). This noble goal requires special sacrifice. The painter who seeks it "will disdain the humbler walks of painting, which, however profitable, can never assure him a permanent reputation" (D 50).

Of course the humbler walks of painting included portraiture, from which Reynolds had already begun to profit handsomely by 1770, when he spoke those words. So it is hard to believe that he spoke them with an absolutely straight face. But setting aside the question of profit, let us consider just how well he himself resisted the temptations of fashion. The answer is that he often didn't, as even Martin Postle admits. Though he frequently made his portrait subjects express a transcendent "idea," Postle writes, he "was bound by transient conventions to a much greater extent than we are accustomed to allow." To look closely at some of his portraits is to see why he was more than once called a "fashionable artist" in his own time (Postle 42).

In 1776, a few years after Reynolds declared that fashion must be "entirely excluded" from all art worthy of the name, he exhibited at the Royal Academy this painting of the flamboyant Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire (below left):

Joshua Reynolds, Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire (c. 1775). The Devonshire Collection.

Apollo Belvedere (c. AD 120-140). After Leochares. White Marble. Vatican Museum.

Georgiana's pose has recently been linked to that of the Apollo Belvedere (above right), and the landscape behind her includes what David Mannings calls "a distant classical statue, perhaps a philosopher in a toga" (Mannings Text 124). But far more conspicuous than either of these features is her lofty headdress, which is just what London fashion required in 1776. Built of powdered brown hair intertwined with pearls, it is topped by pink and white ostrich-feather plumes. Penny notes that Reynolds modifies the effect of her plumes by curving them back, but they remain conspicuous, and they were surely included at the request of Georgiana, who reportedly prided herself on their extraordinary height even though she mocked her addiction to them a few years later in The Sylph, her semi-autobiographical novel of 1779 (Penny 388).

With or without ostrich feathers, fancy headdresses can be readily found in other portraits by Reynolds dating from the 1770s, even when they offer us "historic" impersonation, such as Mrs. Tollemache as Miranda (1774):

Joshua Reynold, Mrs. Tollemache as Miranda (1773-74). Kenwood House.

As for the clothes worn by Reynolds' subjects, especially by his women, their timeliness--not their timelessness--has been repeatedly documented by Aileen Ribeiro, an expert on eighteenth-century English fashion. In the celebrated Mrs. Siddons, for instance, Ribeiro tells us that her pointed and corseted bodice as well as her "slightly puffed-out hairstyle" exemplify the fashion of the early 1780s (Robeiro, qtd. Reynolds 325):

Joshua Reynolds, Mrs. Siddons as the Tragic Muse (1783-84).

Oil on canvas. Huntington Collection. San Marino, CA.

To state the obvious, a good part of the reason why Reynolds' portraits so often bow to fashion is that he had to depict his subjects with their clothes on. Even when he cast them as mythological figures, who are typically represented in the nude, he could not present them that way. In Mrs. Hale as Euphrosyne, for instance, she appears as one of the three graces:

Joshua Reynolds, Mrs. Hale as Euphrosyne (1762-64).

Oil on canvas. Harewood House, Yorkshire, UK

Yet Euphrosyne and the other two graces are typically represented in the nude, and would be sculpted that way by Canova some twenty-five years after Reynolds' death--about ten years after he sculpted Napoleon in the nude for Apsley House:

Antonio Canova, The Three Graces (1817).

London, Victoria and Albert Museum.

Antonio Canova, Napoleon as Mars

the Peacemaker (1802-06). London, Apsley House.

But unlike the subjects of Canova's Three Graces and his Napoleon, Mrs. Hale appears fully clothed. Likewise, even in his non-commissioned painting of Miss Morris as Hope Nursing Love, which replicates (as we've seen) the pose of Michelangelo's nude Leda, a winged Cupid is suckled by a woman whose form--whether ideal or not--is engulfed in draperies.

Pictures like these suggest that whenever Reynolds paints a woman who can be recognized, whether or not she is said to impersonate someone else, her form must be enveloped--which is to say largely hidden-- in clothing. In 1762, Reynolds exhibited Lady Waldegrave and her Daughter as "A lady and her child, in the character of Dido embracing Cupid." The neckline of her dress is low, but still covers her breasts:

Joshua Reynolds, Lady Waldegrave and Her Daughter (1762).

Oil on canvas. Condé Museum, Château de Chantilly, France.

Only in history paintings utterly free of portraiture does Reynolds feel free to expose the body of his subjects, as in Cymon and Iphigenia, which is partly indebted to Titian's Venus of Urbino or, more to the point--in The Death of Dido (1781):

Joshua Reynolds, Cymon and Iphigenia

(c. 1775-89). Oil on canvas.

Royal Collection

Trust, Buckingham Palace, London.

Titian, Venus of Urbino (1534). Oil on canvas.

Florence, Uffizi.

Joshua Reynolds, The Death of Dido

(c.1775-81). Oil on canvas.

Royal Collection Trust.

Buckingham Palace, London.

The Death of Dido exemplifies something else that separates Reynolds' history paintings from his portraits: the distorting effect of passion. Not just fully exposed, Dido's right breast awkwardly protrudes beneath a stretched neck and a lolling, open-mouthed head, with a single arm thrust out straight behind her. In showing just one of her arms, Reynolds breaks a rule that he himself laid down in Discourse 12, when he curiously decreed that paintings must "never" fail to "shew both hands" of the "principal figure, . . . that it should never be a question, what is become of the other hand" (D 216). But Reynolds breaks not only his own rule about hands. To express Dido's suicidal despair, he also breaks what G.E. Lessing had recently defined--in 1766--as "the supreme law of the visual arts" among the ancients--namely the law of beauty (Lessing 15). According to Lessing. everything expressed in art must be "subordinate" to beauty, and however much Reynolds knew about the Laocoon, he sounds very much like Lessing when he declares--in Discourse 5--that "the most perfect beauty in its most perfect state" cannot be united with the expression of "passions, all of which produce distortion and deformity, more or less, in the most beautiful faces" (D 78, emphasis mine). Unlike Lessing, however, Reynolds believed that beauty and expression were "contrary excellences." Consequently, he taught, painters must choose between them, for if they try to make the expression of passion perfectly beautiful, they will sink "into the insipid" (D 78). All of this helps to explain the radical difference between Reynolds' portraits and a painting such as this one. In his portraits, especially of women, Reynolds aims at beauty. In history paintings such as this one, he sacrifices beauty to the deforming effects of passion.

Likewise, Reynolds did not hesitate to sacrifice pedagogical consistency to grander ends. Consider what he says about art and imagination. In Discourse 3, he says that painters should "strive for fame, by captivating the imagination" (D 42), and in his very last discourse, he likewise indicates that great painting "addresses itself not just to the eye, but "to the imagination." Yet in Discourse 8, he posits what he calls a "fixed and indispensable rule" of art: unlike poetry, which can stir the imagination of a reader with indistinct and suggestive words, painting must give everything a distinct, precise, and determinate form, leaving absolutely nothing to the imagination (D 164). For this reason Reynolds commends Falconet's critique of the ancient Greek painter Timanthes for veiling the face of Agamemnon in his painting of the sacrifice of Iphigenia. Even if the eponymous hero of Euripides' Agamemnon did cover his face at the sacrifice, the painter must reveal it because painting --according to this Discourse of Reynolds-- must never leave anything to the imagination.

Yet if history painting cannot express passion without sacrificing perfect beauty, it cannot address the imagination--as Reynolds elsewhere says it must do--without leaving something for the viewer to imagine:

Joshua Reynolds, A Nymph and Cupid (1784).

Oil on canvas. London, National Gallery.

While this painting exposes both of the lady's breasts, her bent right arm conceals half of her face, which enhances her seductiveness; since Cupid is loosening her ribbon belt, the whole painting exploits the erotic power of suggestive concealment, of concealment that addresses the imagination.

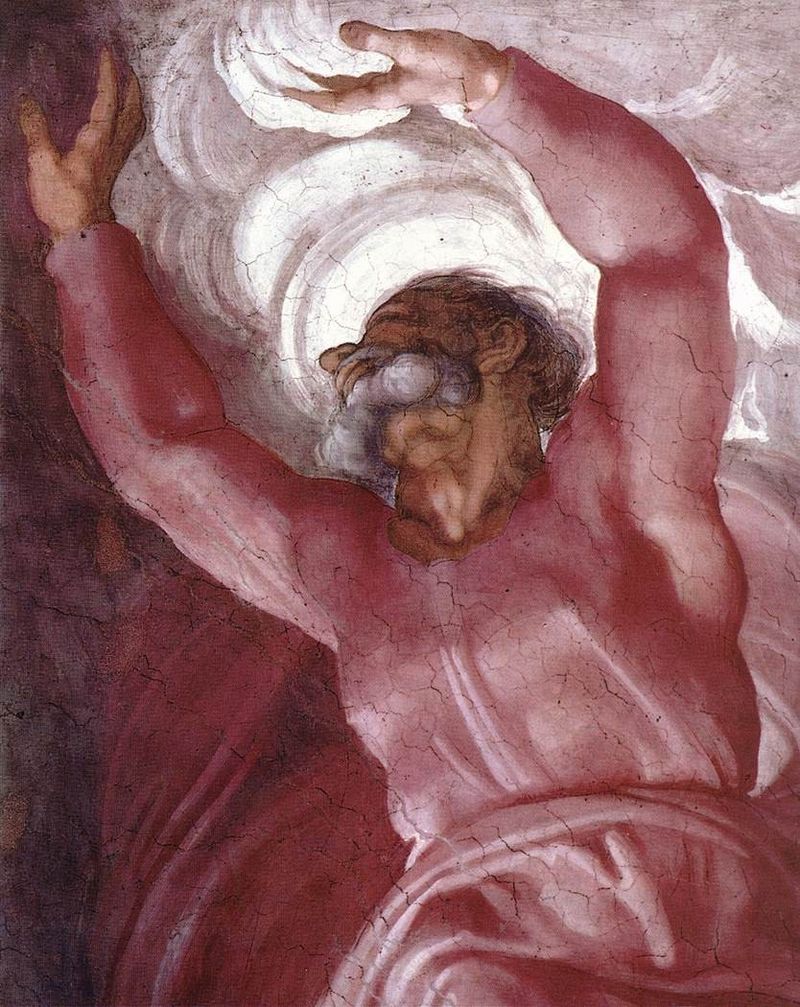

Where then--beneath and behind the rules that Reynolds cannot even obey himself--can we find the essence of the great style as he not only conceived it but strove to incorporate it in his own work? The answer, I think, may be found in his final discourse, where he reveals his own method of composition in the advice he gives to young painters. To compose their paintings, he says, they should make a whole--ponere totum-- from parts furnished by great paintings, specifically from the "attitudes" or poses of particular figures in them. For instance, says Reynolds, Titian took from the Sistine Chapel frescoes of Michelangelo the pose of God separating light from darkness. "[E]xtraordinary as it may seem," he explains, Titian uses this pose in The Battle of Cadore to depict a General falling off his horse in the very center of the painting. Thus, says Reynolds, he changes the purpose of the figure without changing its pose.

Michelangelo, Separation of Light

from Darkness (1512),

Sistine Chapel,

Vatican City.

Titian, Battle of Cadore (1538-39).

Copy of painting

destroyed by fire in 1577, detail.

Florence, Uffizi.

Reynolds' advice here springs not only from his study of Titian but from his own practice, from the way he composed his own paintings--in portraiture as well as history. In the famous Three Ladies Adorning a Herm of Hymen (below left), we now know that the poses of Barbara and Elizabeth--left and center-- come from the two figures at left and center in Francesco Romanelli's Sleeping Silenus (below center). We also know that the pose of Anne, on the right in Reynolds's picture, comes from the pose of Aeneas in another painting by Romanelli, Aeneas and the Golden Bough (below right). By putting these three poses together, Reynolds composed a whole, a totum, that became the blueprint for his triple portrait:

Left: Joshua Reynolds, Three Ladies Adorning a Herm of Hymen (1773). Oil on canvas. Tate Britain, London.

Center: Michel Natalis, Engraving after Giovanni Francesco Romanelli, Sleeping Silenus (1632-33). Detail. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum.

Right: Cornelis Bloemaert, engraving after Giovanni Francesco Romanelli, The Golden Bough, 17th century, detail. New York, Metropolitan Museum.

Like Titian in The Battle of Cadore, Reynolds changes the purpose of his figures while keeping their poses intact. In other words, he leaves behind the original significance of these poses--playing a joke on Silenus, plucking the Golden Bough--in order to make them participate in a composition with an altogether different meaning. The carryover, then, is not semiotic but purely formal and geometric. Using the poses furnished by Romanelli, Reynolds creates a strong diagonal running from Barbara's right hand at lower left through the extended arms of Elizabeth in the center to the uplifted arms of Anne at right. The geometry of the painting generates a grandeur that is hardly diminished by the ladies' looped and plaited hairstyles, which--as usual in Reynolds' portraits--express the fashion of the time. On the right, standing between Elizabeth and Anne, the strict vertical of the statue reaches almost to the top of the painting and thus seems to form a triangle with the diagonal of arms ascending to it. But the statue is shadowed, and its rectilinear rigidity is offset by the bright white flowing draperies of the lady at right. Furthermore, her upraised arms compose a partial circle, which is also suggested by the garland she holds up, the garland hanging down in the middle, and the necklines of the two sisters at left and center. Thus straight line and curve--triangle and circle--collaborate to signify marital union. Nicholas Penny tells us that in the early 1750s, when Reynolds was studying art in Rome, he marked and translated a passage from Fréart on the importance of studying "geometry, perspective and anatomy" (Penny 19). This painting suggests that he mastered at least the geometry of art.

One more example of this mastery can be found in what was perhaps the greatest achievement of Reynolds' final years: his portrait of Lord Heathfield, Governor of Gibraltar.

Joshua Reynolds, Lord Heathfield, Governor of Gibraltar (1787).

Oil on canvas. London, National Portrait Gallery.

To commemorate Heathfield's role in defending Gibraltar against the Spanish siege of 1779-83, Reynolds puts the great key of Gibraltar's fortress in his hand and poses him against a cannon at lower left and a massive black cloud of artillery smoke in the sky overhead. Besides these unmistakable signs of Heathfield's historic action, the great style once again reveals itself in Reynolds' geometry, which in this case seems to be entirely his own, unaided by any poses plucked from the work of his precursors. Paralleling the diagonal of the cannon at lower left, the left side of Heathfield's coat rises into a white triangle just below his chest, where the right side of his coat slants away to his swordhilt and thus helps to define a triangular base for the figure as a whole. Reinforcing this diagonal at lower right is the rough edge of the black smoke at upper left, so that from upper left to lower right the painting is riven almost in two, but with Heathfield majestically filling the center. And in that center, or rather just to the right of center, we find a circle made by the little grey arch of Heathfield's wig, his halfway folded arms, his extended hands (both hands this time!), and of course the all-important key, which closes the circle. If we wonder whether or not Reynolds could thus achieve the great style and the narrative resonance of history painting without sacrificing the special demands of portraiture, let us note what the Morning Herald wrote of this picture in September 1788: "a stronger likeness was never seen from the pencil of Sir Joshua." In this painting at least, Sir Joshua served both of his masters magisterially.

WORKS CITED

Barrell, John. The Political Theory of Painting from Reynolds to Hazlitt:

The Body of the Public. New Haven, Yale UP, 1986.

Lessing, G.E. Laocoon: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and

Poetry, ed. and trans. Edward Allan McCormack. Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins UP, 1984.

Mannings, David, and Martin Postle, Joshua Reynolds: A Complete

Catalogue of His Paintings. Plates and Text. New Haven: Yale UP, 2000.

Penny, Nicholas, ed. Reynolds. New York: Harry N. Abrams,

1986.

Postle, Martin. Sir Joshua Reynolds, The Subject Pictures.

New York, NY : Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Reynolds, Joshua. Discourses on Art [D] ed. Robert Wark. San Marino,

CA: Huntington Library, 1959.

Ribeiro, Aileen. "Some Evidence of the Influence of the Dress of the

Seventeenth Century on Costume in Eighteenth-century Female

Portraiture," Burlington Magazine XCIX (December 1977):

834-40.

Wendorf, Richard. Sir Joshua Reynolds: The Painter in Society.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1996.